Latin translations of the 12th century

Latin translations of the 12th century were spurred by a major search by European scholars for new learning unavailable in western Europe at the time; their search led them to areas of southern Europe, particularly in central Spain and Sicily, which recently had come under Christian rule following their reconquest in the late 11th century.

Excepting a few persons promoting Boethius, such as Gerbert of Aurillac, philosophical thought was developed little in Europe for about two centuries.

[9] The small population of the Crusader Kingdoms contributed very little to the translation efforts, though Sicily, still largely Greek-speaking, was more productive.

[10] Unlike the interest in the literature and history of classical antiquity during the Renaissance, 12th century translators sought new scientific, philosophical and, to a lesser extent, religious texts.

As a consequence the Norman Kingdom of Sicily maintained a trilingual bureaucracy, which made it an ideal place for translations.

[17] A copy of Ptolemy's Almagest was brought back to Sicily by Henry Aristippus, as a gift from the Emperor to King William I. Aristippus, himself, translated Plato's Meno and Phaedo into Latin, but it was left to an anonymous student at Salerno to travel to Sicily and translate the Almagest, as well as several works by Euclid, from Greek to Latin.

Admiral Eugene of Sicily translated Ptolemy's Optics into Latin, drawing on his knowledge of all three languages in the task.

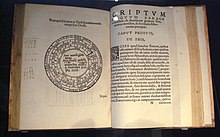

Fibonacci presented the first complete European account of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system from Arabic sources in his Liber Abaci (1202).

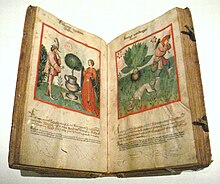

In 13th century Sicily, Faraj ben Salem translated Rhazes' al-Hawi as Continens as well as Ibn Butlan's Tacuinum Sanitatis.

Most notable among these was Gerbert of Aurillac (later Pope Sylvester II) who studied mathematics in the region of the Spanish March around Barcelona.

[25] The early translators in Spain focused heavily on scientific works, especially mathematics and astronomy, with a second area of interest including the Qur'an and other Islamic texts.

In 1142 he called upon Robert of Ketton and Herman of Carinthia, Peter of Poitiers, and a Muslim known only as "Mohammed" to produce the first Latin translation of the Qur'an (the Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete).

Plato of Tivoli's translations into Latin include al-Battani's astronomical and trigonometrical work De Motu Stellarum, Abraham bar Hiyya's Liber Embadorum, Theodosius of Bithynia's Spherics, and Archimedes' Measurement of a Circle.

[31] In 1126, Muhammad al-Fazari's Great Sindhind (based on the Sanskrit works of Surya Siddhanta and Brahmagupta's Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta) was translated into Latin.

[33] The Pseudo-Platonic Book of the Cow, a 9th-century Arabic work on natural magic, was translated into Latin in the 12th century, probably in Spain.

[34] Toledo, with a large population of Arabic-speaking Christians (Mozarabs) had been an important center of learning since as early as the end of the 10th century, when European scholars traveled to Spain to study subjects that were not readily available in the rest of Europe.

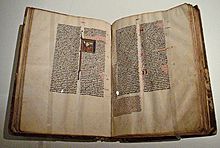

[38] The most productive of the Toledo translators at that time was Gerard of Cremona,[39] who translated 87 books,[40] including Ptolemy's Almagest, many of the works of Aristotle, including his Posterior Analytics, Physics, On the Heavens, On Generation and Corruption, and Meteorology, al-Khwarizmi's On Algebra and Almucabala, Archimedes' On the Measurement of the Circle, Euclid's Elements of Geometry, Jabir ibn Aflah's Elementa Astronomica,[30] al-Kindi's On Optics, al-Farghani's On Elements of Astronomy on the Celestial Motions, al-Farabi's On the Classification of the Sciences, the chemical and medical works of al-Razi (Rhazes),[13] the works of Thabit ibn Qurra and Hunayn ibn Ishaq,[41] and the works of al-Zarqali, Jabir ibn Aflah, the Banu Musa, Abu Kamil, Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi, and Ibn al-Haytham (Not including the Book of Optics, because the catalog of the works of Gerard of Cremona does not list that title; however the Risner compilation of Opticae Thesaurus Septem Libri also includes a work by Witelo and also de Crepusculis, which Risner incorrectly attributed to Alhazen, and which was translated by Gerard of Cremona).

By insisting that the translated output was "llanos de entender" ("easy to understand"),[44] they reached a much wider audience both within Spain and in other European countries, as many scholars from places like Italy, Germany, England or the Netherlands, who had moved to Toledo in order to translate medical, religious, classical and philosophical texts, brought back to their countries the acquired knowledge.

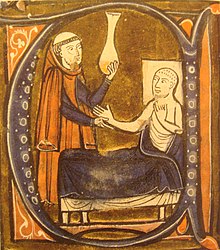

[23] In 14th century Lerida, John Jacobi translated Alcoati's medical work Libre de la figura del uyl into Catalan and then Latin.

[48] Adelard associated with other scholars in Western England such as Peter Alfonsi and Walcher of Malvern who translated and developed the astronomical concepts brought from Spain.

[50] In 13th century Montpellier, Profatius and Bernardus Honofredi translated the Kitab al-Aghdhiya by Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) as De regimine sanitatis; and Armengaud translated the al-Urjuza fi al-Tibb, a work combining the medical writings of Avicenna and Averroes, as Cantica cum commento.