Tropical cyclogenesis

Tropical cyclogenesis involves the development of a warm-core cyclone, due to significant convection in a favorable atmospheric environment.

[2] Tropical cyclogenesis requires six main factors: sufficiently warm sea surface temperatures (at least 26.5 °C (79.7 °F)), atmospheric instability, high humidity in the lower to middle levels of the troposphere, enough Coriolis force to develop a low-pressure center, a pre-existing low-level focus or disturbance, and low vertical wind shear.

[7] There are six main requirements for tropical cyclogenesis: sufficiently warm sea surface temperatures, atmospheric instability, high humidity in the lower to middle levels of the troposphere, enough Coriolis force to sustain a low-pressure center, a preexisting low-level focus or disturbance, and low vertical wind shear.

[12] A recent example of a tropical cyclone that maintained itself over cooler waters was Epsilon of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season.

Maps created from this equation show regions where tropical storm and hurricane formation is possible, based upon the thermodynamics of the atmosphere at the time of the last model run.

[16] This is a balance condition found in mature tropical cyclones that allows latent heat to concentrate near the storm core; this results in the maintenance or intensification of the vortex if other development factors are neutral.

In smaller systems, the development of a significant mesoscale convective complex in a sheared environment can send out a large enough outflow boundary to destroy the surface cyclone.

Moderate wind shear can lead to the initial development of the convective complex and surface low similar to the mid-latitudes, but it must diminish to allow tropical cyclogenesis to continue.

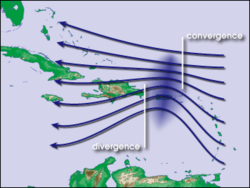

[21][22] There are cases where large, mid-latitude troughs can help with tropical cyclogenesis when an upper-level jet stream passes to the northwest of the developing system, which will aid divergence aloft and inflow at the surface, spinning up the cyclone.

[24] In the North Atlantic, a distinct hurricane season occurs from June 1 through November 30, sharply peaking from late August through October.

The Northwest Pacific sees tropical cyclones year-round, with a minimum in February and a peak in early September.

On rare occasions, such as Pablo in 2019, Alex in 2004,[32] Alberto in 1988,[33] and the 1975 Pacific Northwest hurricane,[34] storms may form or strengthen in this region.

[35] Areas within approximately ten degrees latitude of the equator do not experience a significant Coriolis force, a vital ingredient in tropical cyclone formation.

Notable examples of these "Mediterranean tropical cyclones" include an unnamed system in September 1969, Leucosia in 1982, Celeno in 1995, Cornelia in 1996, Querida in 2006, Rolf in 2011, Qendresa in 2014, Numa in 2017, Ianos in 2020, and Daniel in 2023.

[43] Tropical cyclogenesis is extremely rare in the far southeastern Pacific Ocean, due to the cold sea-surface temperatures generated by the Humboldt Current, and also due to unfavorable wind shear; as such, Cyclone Yaku in March 2023 is the only known instance of a tropical cyclone impacting western South America.

Besides Yaku, there have been several other systems that have been observed developing in the region east of 120°W, which is the official eastern boundary of the South Pacific basin.

[50] Tropical cyclones typically began to weaken immediately following and sometimes even prior to landfall as they lose the sea fueled heat engine and friction slows the winds.

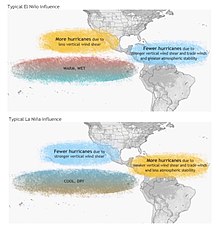

El Niño (ENSO) shifts the region (warmer water, up and down welling at different locations, due to winds) in the Pacific and Atlantic where more storms form, resulting in nearly constant accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) values in any one basin.

During El Niño episodes, tropical cyclones tend to form in the eastern part of the basin, between 150°E and the International Date Line (IDL).

As the oscillation propagates from west to east, it leads to an eastward march in tropical cyclogenesis with time during that hemisphere's summer season.

[58] Since 1984, Colorado State University has been issuing seasonal tropical cyclone forecasts for the north Atlantic basin, with results that they claim are better than climatology.

[59] The university claims to have found several statistical relationships for this basin that appear to allow long range prediction of the number of tropical cyclones.