Cone

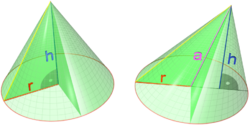

A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base (frequently, though not necessarily, circular) to a point called the apex or vertex that is not contained in the base.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines, or lines connecting a common point, the apex, to all of the points on a base.

Each of the two halves of a double cone split at the apex is called a nappe.

Depending on the author, the base may be restricted to be a circle, any one-dimensional quadratic form in the plane, any closed one-dimensional figure, or any of the above plus all the enclosed points.

If the enclosed points are included in the base, the cone is a solid object; otherwise it is an open surface, a two-dimensional object in three-dimensional space.

In common usage in elementary geometry, cones are assumed to be right circular, i.e., with a circle base perpendicular to the axis.

[1] If the cone is right circular the intersection of a plane with the lateral surface is a conic section.

The perimeter of the base of a cone is called the "directrix", and each of the line segments between the directrix and apex is a "generatrix" or "generating line" of the lateral surface.

The aperture of a right circular cone is the maximum angle between two generatrix lines; if the generatrix makes an angle θ to the axis, the aperture is 2θ.

In optics, the angle θ is called the half-angle of the cone, to distinguish it from the aperture.

[1] A generalized cone is the surface created by the set of lines passing through a vertex and every point on a boundary (also see visual hull).

of any conic solid is one third of the product of the area of the base

[4] In modern mathematics, this formula can easily be computed using calculus — it is, up to scaling, the integral

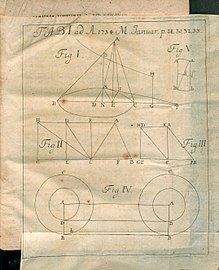

Without using calculus, the formula can be proven by comparing the cone to a pyramid and applying Cavalieri's principle – specifically, comparing the cone to a (vertically scaled) right square pyramid, which forms one third of a cube.

This formula cannot be proven without using such infinitesimal arguments – unlike the 2-dimensional formulae for polyhedral area, though similar to the area of the circle – and hence admitted less rigorous proofs before the advent of calculus, with the ancient Greeks using the method of exhaustion.

This is essentially the content of Hilbert's third problem – more precisely, not all polyhedral pyramids are scissors congruent (can be cut apart into finite pieces and rearranged into the other), and thus volume cannot be computed purely by using a decomposition argument.

[5] The center of mass of a conic solid of uniform density lies one-quarter of the way from the center of the base to the vertex, on the straight line joining the two.

For a circular cone with radius r and height h, the base is a circle of area

and so the formula for volume becomes[6] The slant height of a right circular cone is the distance from any point on the circle of its base to the apex via a line segment along the surface of the cone.

The lateral surface area of a right circular cone is

In implicit form, the same solid is defined by the inequalities where More generally, a right circular cone with vertex at the origin, axis parallel to the vector

In the Cartesian coordinate system, an elliptic cone is the locus of an equation of the form[7] It is an affine image of the right-circular unit cone with equation

From the fact, that the affine image of a conic section is a conic section of the same type (ellipse, parabola,...), one gets: Obviously, any right circular cone contains circles.

This is also true, but less obvious, in the general case (see circular section).

The intersection of an elliptic cone with a concentric sphere is a spherical conic.

In projective geometry, a cylinder is simply a cone whose apex is at infinity.

[8] Intuitively, if one keeps the base fixed and takes the limit as the apex goes to infinity, one obtains a cylinder, the angle of the side increasing as arctan, in the limit forming a right angle.

According to G. B. Halsted, a cone is generated similarly to a Steiner conic only with a projectivity and axial pencils (not in perspective) rather than the projective ranges used for the Steiner conic: "If two copunctual non-costraight axial pencils are projective but not perspective, the meets of correlated planes form a 'conic surface of the second order', or 'cone'.

In this case, one says that a convex set C in the real vector space

| 1. | A cone and a cylinder have radius r and height h . |

| 2. | The volume ratio is maintained when the height is scaled to h' = r √ π . |

| 3. | Decompose it into thin slices. |

| 4. | Using Cavalieri's principle, reshape each slice into a square of the same area. |

| 5. | The pyramid is replicated twice. |

| 6. | Combining them into a cube shows that the volume ratio is 1:3. |