Federal Republic of Central America

There have been several attempts by the republic's successor states during the 19th and 20th centuries to reunify Central America through diplomatic and military means, but none succeeded in uniting all five former members for more than one year.

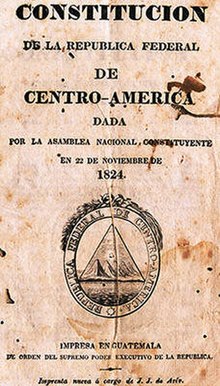

The country's initial name, adopted at independence from the First Mexican Empire on 1 July 1823, was the United Provinces of Central America (Spanish: Provincias Unidas del Centro de América).

[5] In the years shortly after independence, some official government documents referred to the country as the Federated States of Central America (Estados Federados del Centro de América).

[30][31][32] General José Anacleto Ordóñez launched a rebellion against conservative Nicaraguan political leader Miguel González Saravia y Colarte [es], capturing several cities.

[34] When news of Iturbide's abdication reached Filísola on 29 March, he called for Central American political leaders to establish a congress to determine the region's future.

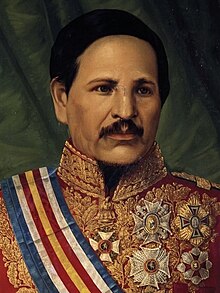

[1][39] José Matías Delgado was Central America's provisional president until 10 July 1823, when the National Constituent Assembly appointed a triumvirate [es] consisting of Arce, Juan Vicente Villacorta and Pedro Molina Mazariegos.

[71] In August 1825, in response to the arrival of 28 French warships in the Caribbean Sea, Arce called for the army to raise 10,000 soldiers to defend their country against a European invasion.

[75] Despite a minor rebellion in Costa Rica led by José Zamora, who called himself a "vassal of the king of Spain", the feared European invasion did not take place.

In response to Barrundia's arrest, Lieutenant Governor Cirilo Flores [es] moved the Guatemalan state government to Quetzaltenango and passed several anti-clerical laws.

[79][80] In October 1826, Arce called for a special election to install a new Guatemalan government;[81] the conservatives won, and Mariano Aycinena became governor of Guatemala on 1 March 1827.

[85][86] While Arce was campaigning in El Salvador, he sent a division of soldiers commanded by Colonel José Justo Milla into Honduras to arrest liberal Honduran Governor Dionisio de Herrera.

[93] Beltranena's government warned its citizens that Morazán's primary objective was to destroy the Catholic Church; Morazán refuted the Guatemalan government's warning, saying that his Christian "Protector Allied Army of the Law" ("Ejército Aliado Protector de la Ley")[94] did not seek to destroy the church and sought only to liberate Guatemala from "the wrongs [they had] suffered" (los males que habéis sufrido").

[104] In May 1829, Morazán sent a letter to the Mexican minister of external relations falsely claiming that Central American refugees fleeing to Mexico were actually enemy forces who sought to "chain and submit their towns to the Spanish yoke" ("encadenar y someter sus pueblos al yugo español").

Similar rebellions against Prado broke out in Ahuachapán, Chalatenango, Izalco, San Miguel, Tejutla and Zacatecoluca,[136] but were quickly suppressed by Salvadoran soldiers.

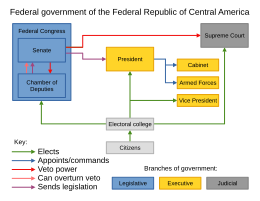

Reforms included allowing the president to veto laws passed by the Federal Congress, abolishing the electoral college and implementing direct elections, and restricting eligibility to hold office to landowners.

[146] Morazán wanted to move the capital to San Salvador, but conservative Salvadoran political leaders resisted his proposal and seceded from the federal republic in January 1832.

George Alexander Thompson, a British diplomat who visited Central America in 1825, said that the federal army would only have been able to resist a Spanish invasion with guerrilla warfare.

In 1836, Morazán said that the federal army had been reduced to "a handful of ancient veterans that have survived the greatest dangers" ("un puñado de antiguos veteranos que han sobrevivido a los mayores peligros").

[201] They supported protectionist economic policies and defended the role of the Catholic Church in Central American society as an arbiter of morality which preserved the status quo.

[220] The Catholic Church influenced Central American politics,[219] but the president and any Supreme Court justice were not allowed to be members of the clergy; only one of each state's two senators could be a clergyman.

[238] Infrastructure between and within the federal republic's states was poor due to Central America's large areas of dense forest and mountainous terrain.

Its canals will shorten the distances throughout the world, strengthen commercial ties with Europe, America, and Asia, and bring that happy region tribute from the four quarters of the globe.

He cited the failure to reach the constitution's republican ideals and separatist sentiment in the five states as an "insurmountable impediment" ("impedimento insalvable") to achieving national unity.

Franklin D. Parker, a history professor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, said that the federal republic's political leaders' failure to abide by and enforce the constitution's provisions ultimately resulted in its collapse.

[252] Nicaraguan writer Salvador Mendieta [es] said that a primary cause of the federal republic's collapse was a lack of efficient communication infrastructure between and within the states.

[183] Philip F. Flemion, a history professor at San Diego State University, attributed the collapse of the federal republic to "regional jealousies, social and cultural differences, inadequate communication and transportation systems, limited financial resources, and disparate political views".

Several attempts have been made at reunification by diplomacy or force during the 19th and 20th centuries, but none lasted longer than a few months or involved all five former members of the Federal Republic of Central America.

[265][263] On 20 June 1895, delegations from El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua signed the Treaty of Amapala and declared the formation of the Greater Republic of Central America.

[267] On 13 November, Salvadoran General Tomás Regalado Romero overthrew President Rafael Antonio Gutiérrez and declared El Salvador's withdrawal from the United States of Central America.

[270][271] Bukele reaffirmed his belief in 2024 that Central America should reunite, saying that the region would be stronger if united but he needed "the will of the peoples" ("la voluntad de los pueblos") to achieve reunification.