Third Dynasty of Ur

It began after several centuries of control, exerted first by the Akkadian Empire, and then, after its fall, by Gutian and independent Sumerian city-state kings.

An illiterate and nomadic people, their rule was not conducive to agriculture, nor record-keeping, and by the time they were expelled, the region was crippled by severe famine and skyrocketing grain prices.

Following Utu-Hengal's reign, Ur-Nammu (originally a general) founded the Third Dynasty of Ur, but the precise events surrounding his rise are unclear.

Ur-Nammu rose to prominence as a warrior-king when he crushed the ruler of Lagash in battle, killing the king himself.

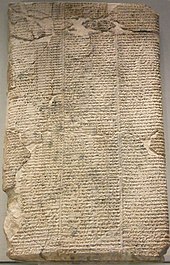

Ur's dominance over the Neo-Sumerian Empire was consolidated with the famous Code of Ur-Nammu, probably the first such law-code for Mesopotamia since that of Urukagina of Lagash centuries earlier.

He captured the city of Susa and the surrounding region, toppling Elamite king Kutik-Inshushinak, while the rest of Elam fell under control of Shimashki dynasty.

[4] In the last century of the 3rd millennium BCE, it is believed that the kings of Ur waged several conflicts around the frontiers of the kingdom.

[6] At the very height of the expansion of Ur, they had taken territory from southeastern Anatolia (modern Turkey) to the Iranian shore of the Persian Gulf, a testimony to the strength of the dynasty.

There are hundreds of texts that explain how treasures were seized by the Ur III armies and brought back to the kingdom after many victories.

In some texts, it also appears that the Shulgi campaigns were the most profitable for the kingdom, although it is likely that the kings and temples of Ur were primarily those that benefited from the spoils of war.

[6] The rulers of Ur III were often in conflict with the highland tribes of the Zagros mountain area who dwelled in the northeastern portion of Mesopotamia.

[10][11] Assyriologists employ many complicated methods for establishing the most precise dates possible for this period, but controversy still exists.

The Amorite kings of the Dynasty of Isin formed successor states to Ur III, starting the Isin-Larsa period.

Over time, Amorite grain merchants rose to prominence and established their own independent dynasties in several south Mesopotamian city-states, most notably Isin, Larsa, Eshnunna, Lagash, and later, founding Babylon as a state.

This year name references an event in which Ur-Nammu attacked the territory of Largas and took grain back to Ur.

Another year-name that has been discovered was the year that Ur-Nammu's daughter became en of the god Nanna and was renamed with the priestess-name of En-Nirgal-ana.

[18][21] The government would then apportion out goods as needed, including funding temples and giving food rations to the needy.

Because it was viewed this way it was thought that any conquest of the city would give the Mesopotamian rulers unacceptable political risks.

This is quite a different picture of a laborer's life than the previous belief that they were afforded no way to move out of the social group they were born into.

Most legal disputes were dealt with locally by government officials called mayors, although their decision could be appealed and eventually overturned by the provincial governor.

Sometimes legal disputes were publicly aired with witnesses present at a place like the town square or in front of the temple.

The Ur III kings oversaw many substantial state-run projects, including intricate irrigation systems and centralization of agriculture.

[26] Various objects made with shell species that are characteristic of the Indus coast, particularly Trubinella Pyrum and Fasciolaria Trapezium, have been found in the archaeological sites of Mesopotamia dating from around 2500-2000 BC.

[28][29][30][31] About twenty seals have been found from the Akkadian and Ur III sites, that have connections with Harappa and often use the Indus script.

[33] Sumerian dominated the cultural sphere and was the language of legal, administrative, and economic documents, while signs of the spread of Akkadian could be seen elsewhere.

The Ur III Dynasty attempted to establish ties to the early kings of Uruk by claiming to be their familial relations.

For example, the Ur III kings often claimed Gilgamesh's divine parents, Ninsun and Lugalbanda, as their own, probably to evoke a comparison to the epic hero.

Another text from this period, known as "The Death of Urnammu", contains an underworld scene in which Ur-Nammu showers "his brother Gilgamesh" with gifts.