Urea cycle

The urea cycle takes place primarily in the liver and, to a lesser extent, in the kidneys.

Urea produced by the liver is then released into the bloodstream, where it travels to the kidneys and is ultimately excreted in urine.

[5] In species including birds and most insects, the ammonia is converted into uric acid or its urate salt, which is excreted in solid form.

Further, the urea cycle consumes acidic waste carbon dioxide by combining it with the basic ammonia, helping to maintain a neutral pH.

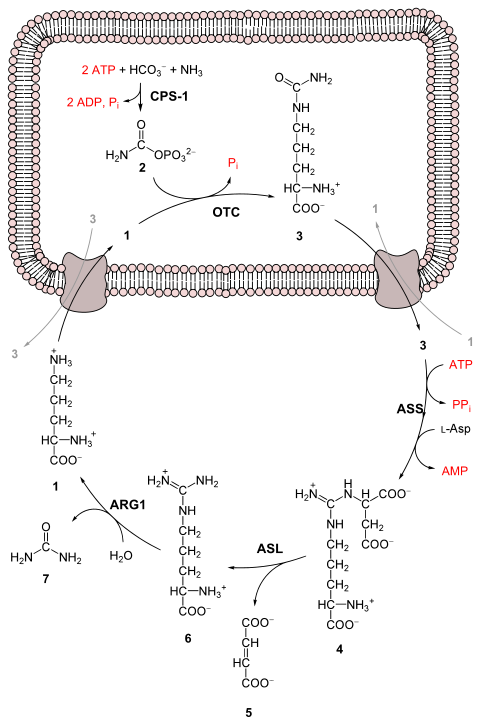

The entire process converts two amino groups, one from NH+4 and one from aspartate, and a carbon atom from HCO−3, to the relatively nontoxic excretion product urea.

However, if gluconeogenesis is underway in the cytosol, the latter reducing equivalent is used to drive the reversal of the GAPDH step instead of generating ATP.

[9] The synthesis of carbamoyl phosphate and the urea cycle are dependent on the presence of N-acetylglutamic acid (NAcGlu), which allosterically activates CPS1.

Although the root cause of NH+4 toxicity is not completely understood, a high [NH+4] puts an enormous strain on the NH+4-clearing system, especially in the brain (symptoms of urea cycle enzyme deficiencies include intellectual disability and lethargy).

[5] The recently born child will typically experience varying bouts of vomiting and periods of lethargy.

[5] New-borns with UCD are at a much higher risk of complications or death due to untimely screening tests and misdiagnosed cases.

[15] On top of these symptoms, if the urea cycle begins to malfunction in the liver, the patient may develop cirrhosis.

[1] If individuals with a defect in any of the six enzymes used in the cycle ingest amino acids beyond what is necessary for the minimum daily requirements, then the ammonia that is produced will not be able to be converted to urea.

Most urea cycle disorders are associated with hyperammonemia, however argininemia and some forms of argininosuccinic aciduria do not present with elevated ammonia.