Uterine prolapse

[4] Preventive efforts include managing medical risk factors, such as chronic lung conditions, smoking cessation, and maintaining a healthy weight.

[2] Pregnancy, vaginal childbirth, or injury can also stretch and weaken the uterosacral ligaments, leading to poor suspension or positioning of the uterus so that it is no longer supported by pelvic floor muscles.

[2] Estrogen deficiency, which can occur during menopause, can affect the production of collagen that is needed to build connective tissue that makes up ligaments and fascia, which can contribute to uterine prolapse.

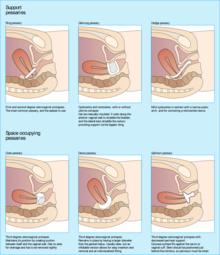

[9] Pessaries are frequently offered as a first-line management option for uterine prolapse, especially amongst people who cannot or do not wish to undergo surgery, due to their affordability and low-risk profile compared to more invasive procedures.

[2] Laparoscopic and robotic approaches to abdominal procedures in prolapse surgery have become more common as they require smaller incision sites, result in less blood loss, and have shorter hospital stays.

Generally, mesh may be considered in instances where the connective tissue is weak or absent, if there is an empty space at the surgical site that needs to be bridged, or if there is a high risk of prolapse recurrence.

[2] However, the use of synthetic mesh transvaginally, or within the vaginal tissue itself, is not indicated and is not routinely used for apical vaginal or uterine prolapse due to a lack of safety and effectiveness data, higher rate of mesh exposure compared with native tissue repair, and lack of data regarding long-term outcomes and complication rates.

[3][2][10] Overall, it appears that quality of life was found to be significantly improved for people with pelvic organ prolapse after surgical or pessary management.

[3] The first mention of uterine prolapse in medical literature was in the Kahun papyrus, circa 1835 B.C.E, which read, "of a woman whose posterior, belly, and branching of her thighs are painful, say thou as to it, it is the falling of the womb.

"[15] The treatment at the time, documented on the Ebers papyrus, was to rub the afflicted person with a mixture of "oil of the earth [and] fedder",[15] or petroleum and manure.

Throughout Western history, advancements in the management of uterine prolapse have been hampered by a poor understanding of female pelvic anatomy.

[15] Therefore, common treatments included fumigation, placing a foul-smelling object near the uterus to convince it to move into the vagina; the use of topical astringents, such as vinegar; and succussion, in which a woman was tied upside-down and shaken until the prolapse reduced.

[15] During the first century C.E., the Greek physician Soranus would disagree with many of these practices and recommended the use of wool, dipped in vinegar or wine and inserted into the vagina, to lift the uterus back into place.

[15] During the mid to late 1800s, surgical attempts to manage uterine prolapse included narrowing the vaginal vault, suturing the perineum, and amputating the cervix.

[15] Following Alwin Mackenrodt's 1895 publication of a comprehensive description of the female pelvic floor connective tissue, Fothergill began working on the Manchester-Fothergill surgery with the belief that the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments were key support structures for the uterus.

[15] Combined with a better understanding of female pelvic floor connective tissue, these ideas would go on to influence surgical approaches for the treatment of uterine prolapse.

As a result, post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse became more common and a growing concern for some surgeons, and new techniques to correct this complication were attempted.

[15] In 1957, Arthure and Savage of London's Charing Cross Hospital, suspecting that uterine prolapse could not be cured with hysterectomy alone, published their surgical technique of sacral hysteropexy.

[3] In 2019, the FDA ordered manufacturers to halt sales of transvaginal mesh intended for repair of pelvic organ prolapse.

[19] Since 2008, a number of class action lawsuits have been filed and settled against several manufacturers of transvaginal mesh after people reported complications following surgery.