Venera

The Venera (Russian: Вене́ра, pronounced [vʲɪˈnʲɛrə] 'Venus') program was a series of space probes developed by the Soviet Union between 1961 and 1984 to gather information about the planet Venus.

Several other failed attempts at Venus flyby probes were launched by the Soviet Union in the early 1960s,[3][4] but were not announced as planetary missions at the time, and hence did not officially receive the "Venera" designation.

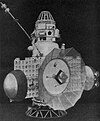

Weighing approximately one ton, and launched by the Molniya-type booster rocket, they included a cruise "bus" and a spherical atmospheric entry probe.

[5] While the Soviet Union initially claimed the craft reached the surface intact, re-analysis, including atmospheric occultation data from the American Mariner 5 spacecraft that flew by Venus the day after its arrival, demonstrated that Venus's surface pressure was 75–100 atmospheres, much higher than Venera 4's 25 atm hull strength, and the claim was retracted.

Designed to jettison nearly half their payload prior to entering the planet's atmosphere, these craft recorded 53 and 51 minutes of data, respectively, while slowly descending by parachute before their batteries failed.

[6]: xiii The Venera 7 probe, launched in August 1970, was the first one designed to survive Venus's surface conditions and to make a soft landing.

Massively overbuilt to ensure survival, it had few experiments on board, and scientific output from the mission was further limited due to an internal switchboard failure that stuck in the "transmit temperature" position.

The Doppler measurements of the Venera 4 to 7 probes were the first evidence of the existence of zonal winds with high speeds of up to 100 metres per second (330 ft/s, 362 km/h, 225 mph) in the Venusian atmosphere (super rotation).

The probes were optimized for surface operations with an unusual design that included a spherical compartment to protect the electronics from atmospheric pressure and heat for as long as possible.

They carried instruments to take scientific measurements of the ground and atmosphere once landed, including cameras, a microphone, a drill and surface sampler, and a seismometer.

The SAR system was crucial in the mapping efforts of the mission and featured an 8-month operational tour to capture Venus's surface at a resolution of 1 to 2 kilometers (0.6 to 1.2 miles).

[8] When the system was switched to radio altimeter mode the antenna operated at an 8-centimeter wavelength band to send and receive signals off of the Venusian surface over a period of 0.67 milliseconds.

An altimeter provided topographical data with a height resolution of 50 m (164 feet), and an East German instrument mapped surface temperature variations.

[9] The VeGa (Cyrillic: ВеГа) probes to Venus and comet 1/P Halley launched in 1984 also used this basic Venera design, including landers but also atmospheric balloons which relayed data for about two days.

[11] Venera-D could incorporate some NASA components, including balloons, a subsatellite for plasma measurements, or a long-lived (24 hours) surface station on the lander.

[17] By sending the first images of Venus' surface back to Earth the Venera missions provided scientists with the ability to relay the achievements with the public.

After analyzing the radar images returned from Venera 15 and 16, it was concluded that the ridges and grooves on the surface of Venus were the result of tectonic deformations.