Andreas Vesalius

His grandfather, Everard van Wesel, was the Royal Physician of Emperor Maximilian, whilst his father, Anders van Wesel, served as apothecary to Maximilian and later valet de chambre to his successor, Charles V. Anders encouraged his son to continue in the family tradition and enrolled him in the Brethren of the Common Life in Brussels to learn Greek and Latin prior to learning medicine, according to standards of the era.

There he studied the theories of Galen under the auspices of Johann Winter von Andernach, Jacques Dubois (Jacobus Sylvius) and Jean Fernel.

[5][4][6] Vesalius was forced to leave Paris in 1536 owing to the opening of hostilities between the Holy Roman Empire and France and returned to the University of Leuven.

His doctoral thesis, Paraphrasis in nonum librum Rhazae medici Arabis clarissimi ad regem Almansorem, de affectuum singularum corporis partium curatione, was a commentary on the ninth book of Rhazes.

Prior to taking up his position in Padua, Vesalius traveled through Italy and assisted the future Pope Paul IV and Ignatius of Loyola to heal those afflicted by leprosy.

[7] Previously these topics had been taught primarily from reading classical texts, mainly Galen, followed by an animal dissection by a barber–surgeon whose work was directed by the lecturer.

In 1543, Vesalius conducted a public dissection of the body of Jakob Karrer von Gebweiler, a notorious felon from the city of Basel, Switzerland.

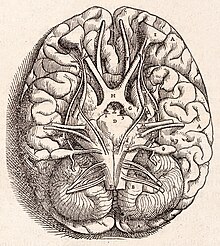

[13] In the same year Vesalius took residence in Basel to help Johannes Oporinus publish the seven-volume De humani corporis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body), a groundbreaking work of human anatomy that he dedicated to Charles V. Many believe it was illustrated by Titian's pupil Jan Stephen van Calcar, but evidence is lacking, and it is unlikely that a single artist created all 273 illustrations in a period of time so short.

At about the same time he published an abridged edition for students, Andrea Vesalii suorum de humani corporis fabrica librorum epitome, and dedicated it to Philip II of Spain, the son of the Emperor.

That work, now collectively referred to as the Fabrica of Vesalius, was groundbreaking in the history of medical publishing and is considered to be a major step in the development of scientific medicine.

Vesalius took up the offered position in the imperial court, where he had to deal with other physicians who mocked him for being a mere barber surgeon instead of an academic working on the respected basis of theory.

During these years he also wrote the Epistle on the China root, a short text on the properties of a medical plant whose efficacy he doubted, as well as a defense of his anatomical findings.

Four years later one of his main detractors and one-time professors, Jacobus Sylvius, published an article that claimed that the human body itself had changed since Galen had studied it.

When he reached Jerusalem he received a message from the Venetian senate requesting him again to accept the Paduan professorship, which had become vacant on the death of contemporary Fallopius.

It appears the story was spread by Hubert Languet, a diplomat under Emperor Charles V and then under the Prince of Orange, who claimed in 1565 that Vesalius had performed an autopsy on an aristocrat in Spain while the heart was still beating, leading to the Inquisition's condemning him to death.

[21] The Fabrica emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical" view of the body, seeing human internal functioning as a result of an essentially corporeal structure filled with organs arranged in three-dimensional space.

When I undertake the dissection of a human pelvis I pass a stout rope tied like a noose beneath the lower jaw and through the zygomas up to the top of the head...

The real significance of the book is his attempt to support his arguments by the location and continuity of the venous system from his observations rather than appeal to earlier published works.

In 1546, three years after the Fabrica, he wrote his Epistola rationem modumque propinandi radicis Chynae decocti, commonly known as the Epistle on the China Root.

Ostensibly an appraisal of a popular but ineffective treatment for gout, syphilis, and stones, this work is especially important as a continued polemic against Galenism and a reply to critics in the camp of his former professor Jacobus Sylvius, now an obsessive detractor.

[25] In 1844, botanists Martin Martens and Henri Guillaume Galeotti published Vesalea, which is a plant genus in the honeysuckle family Caprifoliaceae and it was named in Vesalius's honour.