Vestigiality

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species.

The emergence of vestigiality occurs by normal evolutionary processes, typically by loss of function of a feature that is no longer subject to positive selection pressures when it loses its value in a changing environment.

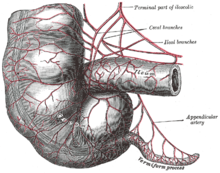

A classic example at the level of gross anatomy is the human vermiform appendix, vestigial in the sense of retaining no significant digestive function.

Such vestigial structures typically are degenerate, atrophied, or rudimentary,[3] and tend to be much more variable than homologous non-vestigial parts.

Similarly, the ostrich uses its wings in displays and temperature control, though they are undoubtedly vestigial as structures for flight.

Some may be of some limited utility to an organism but still degenerate over time if they do not confer a significant enough advantage in terms of fitness to avoid the effects of genetic drift or competing selective pressures.

[5] Vestigial structures have been noticed since ancient times, and the reason for their existence was long speculated upon before Darwinian evolution provided a widely accepted explanation.

He listed a number of them in The Descent of Man, including the muscles of the ear, wisdom teeth, the appendix, the tail bone, body hair, and the semilunar fold in the corner of the eye.

This is why the zoologist Horatio Newman said in a written statement read into evidence in the Scopes Trial that "There are, according to Wiedersheim, no less than 180 vestigial structures in the human body, sufficient to make of a man a veritable walking museum of antiquities.

Therefore, vestigial structures can be considered evidence for evolution, the process by which beneficial heritable traits arise in populations over an extended period of time.

As the function of the trait is no longer beneficial for survival, the likelihood that future offspring will inherit the "normal" form of it decreases.

[15] Douglas Futuyma has stated that vestigial structures make no sense without evolution, just as spelling and usage of many modern English words can only be explained by their Latin or Old Norse antecedents.

[19] Boas and pythons have vestigial pelvis remnants, which are externally visible as two small pelvic spurs on each side of the cloaca.

These spurs are sometimes used in copulation, but are not essential, as no colubrid snake (the vast majority of species) possesses these remnants.

Amphisbaenians, which independently evolved limblessness, also retain vestiges of the pelvis as well as the pectoral girdle, and have lost their right lung.

The human caecum is vestigial, as often is the case in omnivores, being reduced to a single chamber receiving the content of the ileum into the colon.

The ancestral caecum would have been a large, blind diverticulum in which resistant plant material such as cellulose would have been fermented in preparation for absorption in the colon.

[27] Other structures that are vestigial include the plica semilunaris on the inside corner of the eye (a remnant of the nictitating membrane);[28] and (as seen at right) muscles in the ear.

[29] Other organic structures (such as the occipitofrontalis muscle) have lost their original functions (to keep the head from falling) but are still useful for other purposes (facial expression).

One example of this is a gene that is functional in most other mammals and which produces L-gulonolactone oxidase, an enzyme that can make vitamin C. A documented mutation deactivated the gene in an ancestor of the modern infraorder of monkeys, and apes, and it now remains in their genomes, including the human genome, as a vestigial sequence called a pseudogene.

[34] Plants also have vestigial parts, including functionless stipules and carpels, leaf reduction of Equisetum, paraphyses of Fungi.

Product design, like evolution, is iterative; it builds on features and processes that already exist, with limited resources available to make tweaks.

To spend resources on completely weeding out a form that serves no purpose (if at the same time it is not an obstruction either) is not economically astute.

[38] As a final example, soldiers in ceremonial or parade uniform can sometimes be seen wearing a gorget: a small decorative piece of metal suspended around the neck with a chain.