Vinland Map

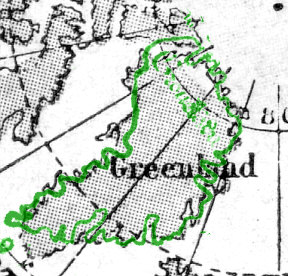

In addition to showing Africa, Asia and Europe, the map depicts a landmass south-west of Greenland in the Atlantic labelled as Vinland (Vinlanda Insula).

Although it was presented to the world in 1965 with an accompanying scholarly book written by British Museum and Yale University librarians, historians of geography and medieval document specialists began to suspect that it might be a fake as soon as photographs of it became available, and chemical analyses have identified one of the major ink ingredients as a 20th-century artificial pigment.

The Vinland map first came to light in 1957 (three years before the discovery of the Norse site at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland in 1960), bound in a slim volume with a short medieval text called the Hystoria Tartarorum (usually called in English the Tartar Relation), and was unsuccessfully offered to the British Museum by London book dealer Irving Davis on behalf of a Spanish-Italian dealer named Enzo Ferrajoli de Ry.

In early 1958, however, Witten's friend Thomas Marston, a Yale librarian, acquired from London book dealer Irving Davis a dilapidated medieval copy of books 21–24 of Vincent of Beauvais's encyclopedic Speculum historiale ("Historical Mirror"), written in two columns on a mix of parchment and paper sheets, with initial capitals left blank, which turned out to be the missing link; the wormholes showing that it had formerly had the map at its beginning and the Relation at its end.

Another point calling the map's authenticity into question was raised at the 1966 Conference: that one caption referred to Bishop Eirik of Greenland "and neighboring regions" (in Latin, "regionumque finitimarum"), a title known previously from the work of religious scholar Luka Jelić (1864–1922).

11, part 1), published shortly after the conference, noted that German researcher Richard Hennig (1874–1951) had spent years, before the Vinland Map was revealed, fruitlessly trying to track Jelić's phrase down in medieval texts.

Skelton's scientific colleagues at the British Museum made a short preliminary examination in 1967 and found that: In 1972, with new technology becoming available, Yale sent the map for chemical analysis by forensic specialist Walter McCrone whose team, using a variety of techniques, found that the yellowish lines contain anatase (titanium dioxide) in a rounded crystalline form manufactured for use in pale pigments since the 1920s, indicating that the ink was modern.

They also confirmed that the ink contained only trace amounts of iron, and that the black line remnants were on top of the yellow, indicating that they were not the remains of a penciled guide-line, as the British Museum staff had speculated.

[7] A new investigation in the early 1980s, by a team under Thomas Cahill at the University of California, Davis, using Particle-Induced X-ray Emission (PIXE) found that only trace amounts (< 0.0062% by weight) of titanium appeared to be present in the ink,[8] which should have been too little for some of McCrone's analyses to detect.

[12] The accumulation of large amounts of PIXE data from other laboratories around the world in the ensuing decades was sufficient by 2008 to show that the Cahill figures for all elements in the inks of the map and its companion documents are at least a thousand times too small,[13] so the discrepancy is due to a problem with their work.

[15] By focusing on this contamination, rich in chromium and iron, he gave Cahill the opportunity to re-emphasise his case in an essay for an expanded version of the 1965 official book, a few years later.

The first was chemist Jacqueline Olin, then a researcher with the Smithsonian Institution, who in the 1970s conducted experiments which produced anatase at an early stage of a medieval iron-gall ink production process.

Examination of her anatase by a colleague, mineralogist Kenneth Towe, showed that it was very different from the neat, rounded crystals found in the Vinland Map and modern pigments.

The initial results were confusing because the unknown substance the British Museum had found across the whole map, effectively ignored by later researchers who were concentrating on the ink, turned out to be trapping tiny traces of fallout deep within the parchment from 1950s nuclear tests.

[22] In 2008, Harbottle's attempt to explain a possible medieval origin for the ink was published, but he was shown by Towe and others to have misunderstood the significance of the various analyses, rendering his theory meaningless.

He stated that, when the McCrone investigation concluded the map to be a forgery in 1974, he was asked by Yale to reveal its provenance as a matter of urgency, and to discuss the possible return of Mr Mellon's money.

"[29] In 2005 a team from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, led by René Larsen, studied the map and its accompanying manuscripts to make recommendations on the best ways to preserve it.

A few months earlier, Kirsten Seaver had suggested that a forger could have found two separate blank leaves in the original "Speculum Historiale" volume, from which the first few dozen pages appeared to be missing, and joined them together with the binding strip.

[2] On the other hand, at the International Conference on the History of Cartography in July 2009, Larsen revealed that his team had continued their investigation after publishing their original report, and he told the press that "All the tests that we have done over the past five years—on the materials and other aspects—do not show any signs of forgery".

[34] In June 2013, it was reported in the British press that a Scottish researcher, John Paul Floyd, claimed to have discovered two pre-1957 references to the Yale Speculum and Tartar Relation manuscripts which shed light on the provenance of the documents.

[28][35] According to one of these sources (an exhibition catalogue), a 15th-century manuscript volume containing books 21-24 of the Speculum Historiale and C. de Bridia's Historia Tartarorum was lent by the Archdiocese of Zaragoza for display at the 1892–93 Exposición Histórico-Europea (an event held in Madrid, Spain to commemorate the voyages of Columbus).