Viral entry

This attachment causes the two membranes to remain in mutual proximity, favoring further interactions between surface proteins.

[2] These basic ideas extend to viruses that infect bacteria, known as bacteriophages (or simply phages).

Typical phages have long tails used to attach to receptors on the bacterial surface and inject their viral genome.

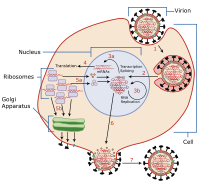

Once a virus enters a cell, replication is not immediate and indeed takes some time (seconds to hours).

Following attachment, the viral envelope fuses with the host cell membrane, causing the virus to enter.

[9] In SARS-CoV-2 and similar viruses, entry occurs through membrane fusion mediated by the spike protein, either at the cell surface or in vesicles.

Research efforts have focused on the spike protein's interaction with its cell-surface receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).

[10] Current prophylaxis against SARS-2 infection targets the spike (S) proteins that harbor the capacity for membrane fusion.

Once inside the cell, the virus leaves the host vesicle by which it was taken up and thus gains access to the cytoplasm.

Entry via the endosome guarantees low pH and exposure to proteases which are needed to open the viral capsid and release the genetic material inside the host cytoplasm.