Marine viruses

Viruses are an important natural means of transferring genes between different species, which increases genetic diversity and drives evolution.

It is thought viruses played a central role in early evolution before the diversification of bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes, at the time of the last universal common ancestor of life on Earth.

[11] They are considered by some to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce by creating multiple copies of themselves through self-assembly, and evolve through natural selection.

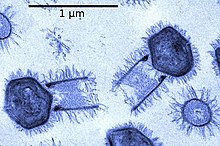

[14][15] Marine viruses, although microscopic and essentially unnoticed by scientists until recently, are the most abundant and diverse biological entities in the ocean.

[4] Quantification of marine viruses was originally performed using transmission electron microscopy but has been replaced by epifluorescence or flow cytometry.

[17] They are a diverse group of viruses which are the most abundant biological entity in marine environments, because their hosts, bacteria, are typically the numerically dominant cellular life in the sea.

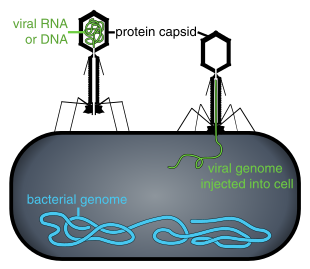

Within a short amount of time, in some cases just minutes, bacterial polymerase starts translating viral mRNA into protein.

[28][21] The cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus, the most abundant oxygenic phototroph on Earth, contributes a substantial fraction of global primary carbon production, and often reaches densities of over 100,000 cells per milliliter in oligotrophic and temperate oceans.

These enable archaea to retain sections of viral DNA, which are then used to target and eliminate subsequent infections by the virus using a process similar to RNA interference.

Algal species such Heterosigma akashiwo and the genus Chrysochromulina can form dense blooms which can be damaging to fisheries, resulting in losses in the aquaculture industry.

[53] Heterosigma akashiwo virus (HaV) has been suggested for use as a microbial agent to prevent the recurrence of toxic red tides produced by this algal species.

[55] Phycodnaviridae cause death and lysis of freshwater and marine algal species, liberating organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus into the water, providing nutrients for the microbial loop.

Studies have used VPR to indirectly infer virus impact on marine microbial productivity, mortality, and biogeochemical cycling.

At least nine types of rhabdovirus cause economically important diseases in species including salmon, pike, perch, sea bass, carp and cod.

[86] The impact of CroV on natural populations of C. roenbergensis remains unknown; however, the virus has been found to be very host specific, and does not infect other closely related organisms.

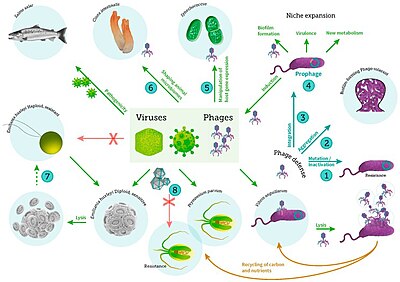

[14] Bacteriophages are harmless to plants and animals, and are essential to the regulation of marine and freshwater ecosystems[91] are important mortality agents of phytoplankton, the base of the foodchain in aquatic environments.

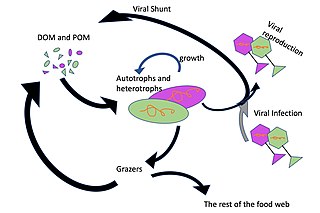

[92] They infect and destroy bacteria in aquatic microbial communities, and are one of the most important mechanisms of recycling carbon and nutrient cycling in marine environments.

[93] In this way, marine viruses are thought to play an important role in nutrient cycles by increasing the efficiency of the biological pump.

Viral shunting helps maintain diversity within the microbial ecosystem by preventing a single species of marine microbe from dominating the micro-environment.

Over the past 2,000 years, anthropogenic activities and climate change have gradually altered the regulatory role of viruses in ecosystem carbon cycling processes.

[110][111][112][113] Viruses are an important natural means of transferring genes between different species, which increases genetic diversity and drives evolution.

[10] It is thought viruses played a central role in early evolution, before bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes diversified, at the time of the last universal common ancestor of life on Earth.

Viruses in the microlayer, the so-called virioneuston, have recently become of interest to researchers as enigmatic biological entities in the boundary surface layers with potentially important ecological impacts.

Given this vast air–water interface sits at the intersection of major air–water exchange processes spanning more than 70% of the global surface area, it is likely to have profound implications for marine biogeochemical cycles, on the microbial loop and gas exchange, as well as the marine food web structure, the global dispersal of airborne viruses originating from the sea surface microlayer, and human health.

This allows nitrogen, carbon, and phosphorus from the living cells to be converted into dissolved organic matter and detritus, contributing to the high rate of nutrient turnover in deep sea sediments.

[106] As their infections are often fatal, they constitute a significant source of mortality and thus have widespread influence on biological oceanographic processes, evolution and biogeochemical cycling within the ocean.

[121] Like in other marine environments, deep-sea hydrothermal viruses affect abundance and diversity of prokaryotes and therefore impact microbial biogeochemical cycling by lysing their hosts to replicate.

[122] However, in contrast to their role as a source of mortality and population control, viruses have also been postulated to enhance survival of prokaryotes in extreme environments, acting as reservoirs of genetic information.

[123] In addition to varied topographies and in spite of an extremely cold climate, the polar aquatic regions are teeming with microbial life.

As grazing by macrofauna is limited in most of these polar regions, viruses are being recognised for their role as important agents of mortality, thereby influencing the biogeochemical cycling of nutrients that, in turn, impact community dynamics at seasonal and spatial scales.

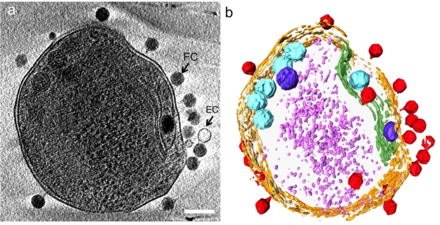

interacting with the marine Prochlorococcus MED4 bacterium

(b) same image visualised by highlighting the cell wall in orange, the plasma membrane in light yellow, the thylakoid membrane in green, carboxysomes in cyan, the polyphosphate body in blue, adsorbed phages on the sides or top of the cell in red, and cytoplasmic granules (probably mostly ribosomes) in light purple. [ 21 ]

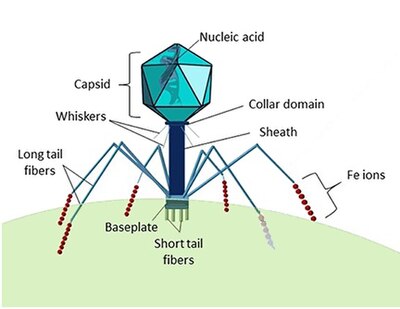

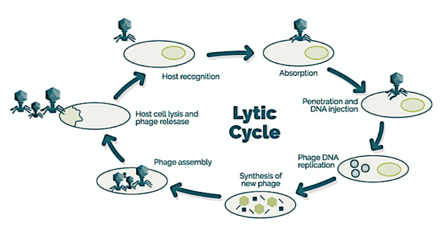

→ attachment: the phage attaches itself to the surface of the host cell

→ penetration: the phage injects its DNA through the cell membrane

→ transcription: the host cell's DNA is degraded and the cell's metabolism is directed to initiate phage biosynthesis

→ biosynthesis: the phage DNA replicates inside the cell

→ maturation: the replicated material assembles into fully formed viral phages

→ lysis : the newly formed phages are released from the infected cell (which is itself destroyed in the process) to seek out new host cells [ 26 ]

including viral infection of bacteria, phytoplankton and fish [ 59 ]