Volcanic ash

[3] Explosive eruptions occur when magma decompresses as it rises, allowing dissolved volatiles (dominantly water and carbon dioxide) to exsolve into gas bubbles.

This increases the heat transfer which leads to the rapid expansion of water and fragmentation of the magma into small particles which are subsequently ejected from the volcanic vent.

Low energy eruptions of basalt produce a characteristically dark coloured ash containing ~45–55% silica that is generally rich in iron (Fe) and magnesium (Mg).

[12] The sulfur and halogen gases and metals are removed from the atmosphere by processes of chemical reaction, dry and wet deposition, and by adsorption onto the surface of volcanic ash.

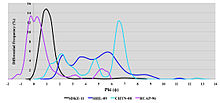

It has long been recognised that a range of sulfate and halide (primarily chloride and fluoride) compounds are readily mobilised from fresh volcanic ash.

In contrast, most high-silica ash (e.g. rhyolite) consists of pulverised products of pumice (vitric shards), individual phenocrysts (crystal fraction) and some lithic fragments (xenoliths).

[24] Ash generated during phreatic eruptions primarily consists of hydrothermally altered lithic and mineral fragments, commonly in a clay matrix.

Lithic morphology in ash is generally controlled by the mechanical properties of the wall rock broken up by spalling or explosive expansion of gases in the magma as it reaches the surface.

Stresses within the "quenched" magma cause fragmentation into five dominant pyroclast shape-types: (1) blocky and equant; (2) vesicular and irregular with smooth surfaces; (3) moss-like and convoluted; (4) spherical or drop-like; and (5) plate-like.

[1] There is good evidence that pyroclastic flows produce high proportions of fine ash by communition and it is likely that this process also occurs inside volcanic conduits and would be most efficient when the magma fragmentation surface is well below the summit crater.

[32] The exposure levels to free crystalline silica in the ash are commonly used to characterise the risk of silicosis in occupational studies (for people who work in mining, construction and other industries,) because it is classified as a human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

These elements may impart a metallic taste to water, and may produce red, brown or black staining of whiteware, but are not considered a health risk.

Volcanic ashfalls are not known to have caused problems in water supplies for toxic trace elements such as mercury (Hg) and lead (Pb) which occur at very low levels in ash leachates.

[48] It is known from the 1783 eruption of Laki in Iceland that fluorine poisoning occurred in humans and livestock as a result of the chemistry of the ash and gas, which contained high levels of hydrogen fluoride.

Following the 1995/96 Mount Ruapehu eruptions in New Zealand, two thousand ewes and lambs died after being affected by fluorosis while grazing on land with only 1–3 mm of ash fall.

[48] Symptoms of fluorosis among cattle exposed to ash include brown-yellow to green-black mottles in the teeth, and hypersensibility to pressure in the legs and back.

[67] Volcanic gases, which are present within ash clouds, can also cause damage to engines and acrylic windshields, and can persist in the stratosphere as an almost invisible aerosol for prolonged periods of time.

On 24 June 1982, a British Airways Boeing 747-236B (Flight 9) flew through the ash cloud from the eruption of Mount Galunggung, Indonesia resulting in the failure of all four engines.

[66] In April 2010, airspace all over Europe was affected, with many flights cancelled-which was unprecedented-due to the presence of volcanic ash in the upper atmosphere from the eruption of the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull.

[69] On 15 April 2010, the Finnish Air Force halted training flights when damage was found from volcanic dust ingestion by the engines of one of its Boeing F-18 Hornet fighters.

However, a new system called Airborne Volcanic Object Infrared Detector (AVOID) has recently been developed by Dr Fred Prata[72] while working at CSIRO Australia[73] and the Norwegian Institute for Air Research, which will allow pilots to detect ash plumes up to 60 km (37 mi) ahead and fly safely around them.

Small accumulations of ash can reduce visibility, produce slippery runways and taxiways, infiltrate communication and electrical systems, interrupt ground services, damage buildings and parked aircraft.

[81] Ash may disrupt transportation systems over large areas for hours to days, including roads and vehicles, railways and ports and shipping.

Research by the New Zealand-based Auckland Engineering Lifelines Group determined theoretically that impacts on telecommunications signals from ash would be limited to low frequency services such as satellite communication.

Ash will increase water turbidity which can reduce the amount of light reaching lower depths, which can inhibit growth of submerged aquatic plants and consequently affect species which are dependent on them such as fish and shellfish.

[33] The 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajokull in Iceland highlighted the impacts of volcanic ash fall in modern society and our dependence on the functionality of infrastructure services.

[38] Preparedness for ashfalls should involve sealing buildings, protecting infrastructure and homes, and storing sufficient supplies of food and water to last until the ash fall is over and clean-up can begin.

At home, staying informed about volcanic activity, and having contingency plans in place for alternative shelter locations, constitutes good preparedness for an ash fall event.

Spare parts and back-up systems should be in place prior to ash fall events to reduce service disruption and return functionality as quickly as possible.

This layer is highly rich in nutrients and is very good for agricultural use; the presence of lush forests on volcanic islands is often as a result of trees growing and flourishing in the phosphorus and nitrogen-rich andisol.