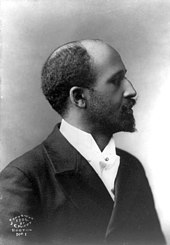

W. E. B. Du Bois

Borrowing a phrase from Frederick Douglass, he popularized the use of the term color line to represent the injustice of the separate but equal doctrine prevalent in American social and political life.

[23] His travel to and residency in the South was Du Bois's first experience with Southern racism, which at the time encompassed Jim Crow laws, bigotry, suppression of black voting, and lynchings; the lattermost reached a peak in the next decade.

At the conclusion of the conference, delegates unanimously adopted "To the Nations of the World", and sent copies of the speech to heads of state who governed large populations of African descent that suffered oppression.

[62] Included were charts, graphs, and maps, which displayed economic, demographic, and sociological data relating to the contemporary and historic living conditions of African Americans, as well as their scientific and cultural achievements.

[90] Reverdy C. Ransom spoke, explaining that Washington's primary goal was to prepare blacks for employment in their current society: "Today, two classes of Negroes ...are standing at the parting of the ways.

This was a unique identity which, according to Du Bois, had been a handicap in the past, but could be a strength in the future: "Henceforth, the destiny of the race could be conceived as leading neither to assimilation nor separatism but to proud, enduring hyphenation.

By this I mean that, like Du Bois the American traditional pragmatic religious naturalism, which runs through William James, George Santayana, and John Dewey, seeks religion without metaphysical foundations."

[97] Two calamities in the autumn of 1906 shocked African Americans, and they contributed to strengthening support for Du Bois's struggle for civil rights to prevail over Booker T. Washington's accommodationist Atlanta Compromise.

Today, the avenues of advancement in the army, navy, civil service, and even business and professional life are continually closed to black applicants of proven fitness, simply on the bald excuse of race and color.

To the contrary, Du Bois asserted that the brief period of African-American leadership in the South accomplished three important goals: democracy, free public schools, and new social welfare legislation.

[111] Du Bois asserted that it was the federal government's failure to manage the Freedmen's Bureau, to distribute land, and to establish an educational system, that doomed African-American prospects in the South.

Du Bois wrote an editorial supporting the Great Migration, because he felt it would help blacks escape Southern racism, find economic opportunities, and assimilate into American society.

Du Bois was not intimidated, and in 1918 he predicted that World War I would lead to an overthrow of the European colonial system and to the "liberation" of colored people worldwide – in China, in India, and especially in the Americas.

[179] In the editorial "Returning Soldiers" he wrote: "But, by the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if, now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.

Infuriated with the distortions, Du Bois published a letter in the New York World, claiming that the only crime the black sharecroppers had committed was daring to challenge their white landlords by hiring an attorney to investigate contractual irregularities.

[192] Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey, promoter of the Back-to-Africa movement and founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA),[193] denounced Du Bois's efforts to achieve equality through integration, and instead endorsed racial separatism.

"[198] Du Bois and Garvey never made a serious attempt to collaborate, and their dispute was partly rooted in the desire of their respective organizations (NAACP and UNIA) to capture a larger portion of the available philanthropic funding.

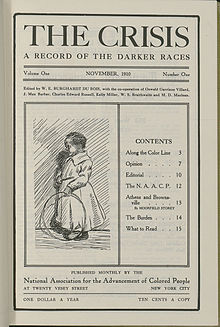

"[200] When Du Bois sailed for Europe in 1923 for the third Pan-African Congress, the circulation of The Crisis had declined to 60,000 from its World War I high of 100,000, but it remained the preeminent periodical of the civil rights movement.

[212] Progressive Era Repression and persecution Anti-war and civil rights movements Contemporary When Du Bois became editor of The Crisis magazine in 1911, he joined the Socialist Party of America on the advice of NAACP founders Mary White Ovington, William English Walling and Charles Edward Russell.

He was not a strong proponent of labor unions or the Communist Party, but he felt that Marx's scientific explanation of society and the economy were useful for explaining the situation of African Americans in the United States.

[238][239] The book presented the thesis, in the words of the historian David Levering Lewis, that "black people, suddenly admitted to citizenship in an environment of feral hostility, displayed admirable volition and intelligence as well as the indolence and ignorance inherent in three centuries of bondage.

[251][252] He admired how the Nazis had improved the German economy, but he was horrified by their treatment of the Jewish people, which he described as "an attack on civilization, comparable only to such horrors as the Spanish Inquisition and the African slave trade".

He came to view the ascendant Japanese Empire as an antidote to Western imperialism, arguing for over three decades after the war that its rise represented a chance to break the monopoly that white nations had on international affairs.

[270] Arthur Spingarn remarked that Du Bois spent his time in Atlanta "battering his life out against ignorance, bigotry, intolerance and slothfulness, projecting ideas nobody but he understands, and raising hopes for change which may be comprehended in a hundred years.

To push the United Nations in that direction, Du Bois drafted a proposal that pronounced "[t]he colonial system of government ... is undemocratic, socially dangerous and a main cause of wars".

"[293] In the spring of 1949, he spoke at the World Congress of the Partisans of Peace in Paris, saying to the large crowd: "Leading this new colonial imperialism comes my own native land built by my father's toil and blood, the United States.

"[294] Du Bois affiliated himself with a leftist organization, the National Council of Arts, Sciences and Professions, and he traveled to Moscow as its representative to speak at the All-Soviet Peace Conference in late 1949.

[315] His primary concern was world peace, and he railed against military actions such as the Korean War, which he viewed as efforts by imperialist whites to maintain colored people in a submissive state.

"[321]: 52 Du Bois became incensed in 1961 when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the 1950 McCarran Internal Security Act, a key piece of McCarthyist legislation that required communists to register with the government.

In China, a crowd of 10,000 people stood in silence for three minutes, and major figures including Mao, Zhou Enlai, Soong Ching-Ling, and Guo Moruo sent messages of condolence to Graham Du Bois.