William Byrd

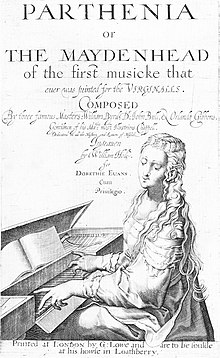

[2] Byrd wrote in many of the forms current in England at the time, including various types of sacred and secular polyphony, keyboard (the so-called Virginalist school), and consort music.

In 1572, following the death of the composer Robert Parsons, who drowned in the Trent near Newark on 25 January of that year, Byrd obtained the post of Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, the largest choir of its kind in England.

[18] The two musicians used the services of the French Huguenot printer Thomas Vautrollier, who had settled in England and previously produced an edition of a collection of Lassus chansons in London (Receuil du mellange, 1570).

Byrd himself may have held Protestant beliefs in his youth, for a recently discovered fragment of a setting of an English translation of Martin Luther's hymn "Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort", which bears an attribution to "Birde" includes the line "From Turk and Pope defend us Lord".

With the influx of missionary priests trained at the English College, Douai (now in France but then part of the Spanish Netherlands), and in Rome from the 1570s onwards, relations between the authorities and the Catholic community took a further turn for the worse.

[24] His ownership of Stondon Place, where he lived for the rest of his life, was contested by Joanna Shelley, with whom he engaged in a legal dispute lasting about a decade and a half.

Byrd's setting is on a massive scale, requiring five-part Decani and Cantoris groupings in antiphony, block homophony and five, six and eight-part counterpoint with verse (solo) sections for added variety.

The songs include elegies for public figures such as the Earl of Essex (1601), the Catholic matriarch and viscountess Montague Magdalen Dacre (With Lilies White, 1608) and Henry Prince of Wales (1612).

Byrd remained in Stondon Massey until his death, due to heart failure, on 4 July 1623, which was noted in the Chapel Royal Check Book in a unique entry describing him as "a Father of Musick".

Despite repeated citations for recusancy and persistent heavy fines, he died a rich man[quantify], having rooms at the time of his death at the London home of the Earl of Worcester.

[29] One of Byrd's earliest compositions was a collaboration with two Chapel Royal singing-men, John Sheppard and William Mundy, on a setting for four male voices of the psalm In exitu Israel for the procession to the font in Easter week.

Two exceptional large-scale psalm motets, Ad Dominum cum tribularer (a8) and Domine quis habitabit (a9), are Byrd's contribution to a paraliturgical form cultivated by Robert White and Parsons.

De lamentatione, another early work, is a contribution to the Elizabethan practice of setting groups of verses from the Lamentations of Jeremiah, following the format of the Tenebrae lessons sung in the Catholic rite during the last three days of Holy Week.

Some texts should probably be interpreted as warnings against spies (Vigilate, nescitis enim) or lying tongues (Quis est homo) or celebration of the memory of martyred priests (O quam gloriosum).

Byrd's setting of the first four verses of Psalm 78 (Deus venerunt gentes) is widely believed to refer to the brutal execution of Fr Edmund Campion in 1581 an event that caused widespread revulsion on the Continent as well as in England.

In 1583 De Monte sent Byrd his setting of verses 1–4 of Vulgate Psalm 136 (Super flumina Babylonis), including the pointed question "How shall we sing the Lord's song in a strange land?"

Byrd evolved a special "cell" technique for setting the petitionary clauses such as miserere mei or libera nos Domine which form the focal point for a number of the texts.

Particularly striking examples of these are the final section of Tribulatio proxima est (1589) and the multi-sectional Infelix ego (1591), a large-scale motet which takes its point of departure from Tribue Domine of 1575.

In 1602, Byrd's patron Edward Somerset, 4th Earl of Worcester, discussing Court fashions in music, predicted that "in winter lullaby, an owld song of Mr Birde, wylbee more in request as I thinke."

Other items from the three-part and four-part section are in a lighter vein, employing a line-by-line imitative technique and a predominant crotchet pulse (The nightingale so pleasant (a3), Is love a boy?

The Battle, which was apparently inspired by an unidentified skirmish in Elizabeth's Irish wars, is a sequence of movements bearing titles such as "The marche to fight", "The battells be joyned" and "The Galliarde for the victorie".

A good example of the last type is the Fantasia a6 (No 2) which begins with a sober imitative paragraph before progressively more fragmented textures (working in a quotation from Greensleeves at one point).

The editions are undated (dates can be established only by close bibliographic analysis),[38] do not name the printer and consist of only one bifolium per partbook to aid concealment, reminders that the possession of heterodox books was still highly dangerous.

All three works contain retrospective features harking back to the earlier Tudor tradition of Mass settings which had lapsed after 1558, along with others which reflect Continental influence and the liturgical practices of the foreign-trained incoming missionary priests.

The greater part of the two collections consists of settings of the Proprium Missae for the major feasts of the church calendar, thus supplementing the Mass Ordinary cycles which Byrd had published in the 1590s.

As Philip Brett has pointed out, most of the items from the four- and three-part sections were taken from the Primer (the English name for the Book of hours), thus falling within the sphere of private devotions rather than public worship.

The vast majority are shorter, with the discursive imitative paragraphs of the earlier motets giving place to double phrases in which the counterpoint, though intricate and concentrated, assumes a secondary level of importance.

These include some of his most famous compositions, notably Praise our Lord, all ye Gentiles (a6), This day Christ was born (a6) and Have mercy upon me (a6), which employs alternating phrases with verse and full scoring and was circulated as a church anthem.

The English Civil War, and the change of taste brought about by the Stuart Restoration, created a cultural hiatus which adversely affected the cultivation of Byrd's music together with that of Tudor composers in general.

In more recent times, Joseph Kerman, Oliver Neighbour, Philip Brett, John Harley, Richard Turbet, Alan Brown, Kerry McCarthy, and others have made major contributions to increasing our understanding of Byrd's life and music.