Women in Mexico

With urbanization beginning in the sixteenth century, following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, cities have provided economic and social opportunities not possible within rural villages.

In the late nineteenth century, as Mexico allowed foreign investment in industrial enterprises, women found increased opportunities to work outside the home.

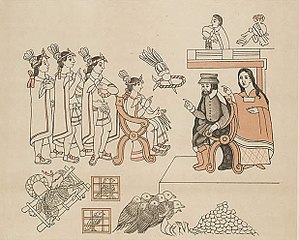

One of the most notable women who assisted Hernán Cortés during the conquest period of Mexico was Doña Marina, or Malinche, who knew both the Nahuatl and Mayan language and later learned Spanish.

European men sought elite Mexican women to marry and have children with, in order to retain or gain a higher status in society.

Toward the end of the Porfiriato, the period when General Porfirio Díaz ruled Mexico (1876–1910), women began pressing for legal equality and the right to vote.

Most often, these women followed the army when a male relative joined and provided essential services such as food preparation, tending to the wounded, mending clothing, burying the dead, and retrieval of items from the battlefield.

In 1914, a count of Pancho Villa’s forces included 4,557 male soldiers, 1,256 soldaderas, and 554 children many of whom were babies or toddlers strapped to their mother’s backs.

Earlier women governors were Griselda Álvarez (Colima, 1979–1985), Beatriz Paredes (Tlaxcala, 1987–1992), Dulce María Sauri (Yucatán, 1991–1994), Rosario Robles Berlanga (Distrito Federal, 1999–2000).

Revered for her evocative self-portraits, Kahlo's oeuvre resonates deeply within the realm of Mexican art history, reflecting themes of identity, pain, and cultural heritage.

[41][42] Carmen Mondragón, also recognized as Nahui Olin, made indelible contributions to Mexican art as a painter, poet, and muse during the early 20th century.

Carmen Parra's artistic oeuvre is distinguished by its engagement with pressing social and political concerns, particularly advocating for women's rights through her work.

Verónica Ruiz de Velasco has garnered recognition for her vivid and emotive paintings, which frequently delve into themes of nature, spirituality, and the rich tapestry of Mexican culture.

Amalia Hernández established the Ballet Folklórico de México, an iconic dance ensemble celebrated for its vibrant performances, notably showcased at the esteemed Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City.

Among them, Dolores del Río stands as a trailblazer, recognized as one of the earliest Latin American actresses to achieve widespread international acclaim.

Meanwhile, Silvia Pinal's multifaceted career spans cinema, theater, and television, with her contributions not only enriching the entertainment landscape but also advocating for cultural advancement and artistic expression within Mexico.

Finally, Verónica Castro's indelible mark on Mexican television, particularly through her roles in beloved telenovelas, cements her legacy as an enduring icon in the nation's cultural heritage.

Within the domain of contemporary Mexican actresses, Salma Hayek emerges as a notable luminary, celebrated for her multifaceted performances and widespread recognition on the global stage.

[44] Conversely, Yalitza Aparicio's pivotal portrayal in Alfonso Cuarón's lauded film "Roma" propelled her into the international spotlight, illuminating her talent and serving as a poignant representation of indigenous women from Oaxaca on the world's cinematic platform.

In 2019, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador signed into law protections and benefits for domestic workers, including access to health care and limits on hours of work.

"[51] According to a 1997 study by Kaja Finkler, domestic abuse is more prevalent in Mexican society as women are dependent on their spouses for subsistence and self esteem, caused by the embedded societal ideology of romantic love, family structure, and residential arrangements.

As Mexico became more urban and industrialized, the government formulated and implemented family planning policies in the 1970s and 80s that aimed at educating Mexicans about the advantages of controlling fertility.

[77] A key component of the educational campaign was the creation of telenovelas (soap operas) that conveyed the government's message about the virtues of family planning.

Mexico pioneered the use of soap operas to shape public attitudes on sensitive issues in a format both accessible and enjoyable to a wide range of viewers.

[79][80] One scholar, the Stanford University historian Ana Raquel Minion, has attributed at least part of Mexico's success to forced sterilization programs.

In her 2018 text Undocumented Lives, she writes: "After the new Ley General of 1974 passed, some medical authorities in public health care institutions responded to the growing pressures to lower birth rates by forcibly sterilizing working-class women immediately after they delivered via cesarean section.

Reproductive health experts have concluded, that "stigma, gender, relationships and ethnicity may all play a role in a woman´s experience in receiving birth control",[85][full citation needed] leading to less, or even denied access to EC.

In the green and gold logo, used in official events and in government social networks five celebrities appear on the motto "Women transforming Mexico.

To her left, it is also drawn Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez (1768–1829), known as "la Corregidora" who played a fundamental role in the conspiracy that gave rise to the beginning of the independence movement from the state of Querétaro.

The nun and neo-Hispanic writer sister sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648–1695), one of the main exponents of the Golden Age of literature in Spanish thanks to her lyrical and dramatic work, both religious and profane stars in the far left of the image.

On the opposite side, the revolutionary Carmen Serdán (1875–1948), is drawn, who strongly supported from the city of Puebla to Francisco Ignacio Madero in his proclamation against the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, which was finally overthrown in 1911.