Writing

The outcome of this activity, also called "writing", and sometimes a "text", is a series of physically inscribed, mechanically transferred, or digitally represented symbols.

[5] Writing can also have knowledge-transforming effects, since it allows humans to externalize their thinking in forms that are easier to reflect on, elaborate on, reconsider, and revise.

[11] Advancements in natural language processing and natural language generation have resulted in software capable of producing certain forms of formulaic writing (e.g., weather forecasts and brief sports reporting) without the direct involvement of humans[12] after initial configuration or, more commonly, to be used to support writing processes such as generating initial drafts, producing feedback with the help of a rubric, copy-editing, and helping translation.

During the course of a day or even a single episode of writing, for example, a writer might instinctively switch among a pencil, a touchscreen, a text-editor, a whiteboard, a legal pad, and adhesive notes as different purposes arise.

[17] As Charles Bazerman explains, the "marking of signs on stones, clay, paper, and now digital memories—each more portable and rapidly traveling than the previous—provided means for increasingly coordinated and extended action as well as memory across larger groups of people over time and space.

"[18] For example, around the 4th millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration in Mesopotamia outgrew human memory, and writing became a more dependable method for creating permanent records of transactions.

[19] On the other hand, writing in both ancient Egypt and Mesoamerica may have evolved through the political necessity to manage the calendar for recording historical and environmental events.

Individual motivations for writing include improvised additional capacity for the limitations of human memory[22] (e.g. to-do lists, recipes, reminders, logbooks, maps, the proper sequence for a complicated task or important ritual), dissemination of ideas and coordination (e.g. essays, monographs, broadsides, plans, petitions, or manifestos), creativity and storytelling, maintaining kinship and other social networks,[23] business correspondence regarding goods and services, and life writing (e.g. a diary or journal).

[26] In many occupations (e.g. law, accounting, software design, human resources), written documentation is not only the main deliverable but also the mode of work itself.

For example, in the course of an afternoon, a wholesaler might receive a written inquiry about the availability of a product line, then communicate with suppliers and fabricators through work orders and purchase agreements, correspond via email to affirm shipping availability with a drayage company, write an invoice, and request proof of receipt in the form of a written signature.

Written rules and procedures typically guide the operations of the various branches, departments, and other bodies of government, which regularly produce reports and other documents as work products and to account for their actions.

[34] Governments at different levels also typically maintain written records on citizens concerning identities, life events such as births, deaths, marriages, and divorces, the granting of licenses for controlled activities, criminal charges, traffic offenses, and other penalties small and large, and tax liability and payments.

Arguments, experiments, observational data, and other evidence collated in the course of research is represented in writing, and serves as the basis for later work.

Prior to official publication, these documents are typically read and evaluated by peer review from appropriate experts, who determine whether the work is of sufficient value and quality to be published.

As the work appears in review articles, handbooks, textbooks, or other aggregations, and others cite it in the advancement of their own research, does it become codified as contingently reliable knowledge.

[39] News and news reporting are central to citizen engagement and knowledge of many spheres of activity people may be interested in about the state of their community, including the actions and integrity of their governments and government officials, economic trends, natural disasters and responses to them, international geopolitical events, including conflicts, but also sports, entertainment, books, and other leisure activities.

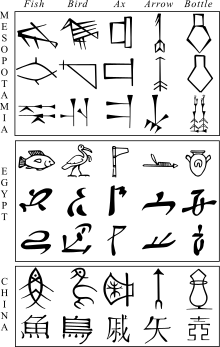

[citation needed] While research into the development of writing during the Neolithic is ongoing, the current consensus is that it first evolved from economic necessity in the ancient Near East.

Writing most likely began as a consequence of political expansion in ancient cultures, which needed reliable means for transmitting information, maintaining financial accounts, keeping historical records, and similar activities.

Around the 4th millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration outgrew the power of memory, and writing became a more dependable method of recording and presenting transactions in a permanent form.

[49] The invention of the first writing systems is roughly contemporary with the emergence of civilisations and the beginning of the Bronze Age during the late 4th millennium BC.

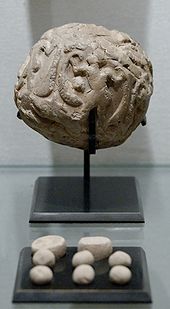

Archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat determined the link between previously uncategorized clay "tokens", the oldest of which have been found in the Zagros region of Iran, and cuneiform, the first known writing.

This script was adapted to another Mesopotamian language, the East Semitic Akkadian (Assyrian and Babylonian) c. 2600 BC, and then to others such as Elamite, Hattian, Hurrian and Hittite.

[citation needed] The earliest known hieroglyphs are about 5,200 years old, such as the clay labels of a Predynastic ruler called "Scorpion I" (Naqada IIIA period, c. 32nd century BC) recovered at Abydos (modern Umm el-Qa'ab) in 1998 or the Narmer Palette, dating to c. 3100 BC, and several recent discoveries that may be slightly older, though these glyphs were based on a much older artistic rather than written tradition.

[citation needed] The world's oldest known alphabet appears to have been developed by Canaanite turquoise miners in the Sinai desert around the mid-19th century BC.

Based on hieroglyphic prototypes, but also including entirely new symbols, each sign apparently stood for a consonant rather than a word: the basis of an alphabetic system.

[59] The earliest surviving examples of writing in China—inscriptions on oracle bones, usually tortoise plastrons and ox scapulae which were used for divination—date from around 1200 BC, during the Late Shang period.

[60] In 2003, archaeologists reported discoveries of isolated tortoise-shell carvings dating back to the 7th millennium BC, but whether or not these symbols are related to the characters of the later oracle bone script is disputed.

In use only briefly (c. 3200 – c. 2900 BC), clay tablets with Proto-Elamite writing have been found at different sites across Iran, with the majority having been excavated at Susa, an ancient city located east of the Tigris and between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers.

The term 'Indus script' is mainly applied to that used in the mature Harappan phase, which perhaps evolved from a few signs found in early Harappa after 3500 BC.

The Phoenician writing system was adapted from the Proto-Canaanite script sometime before the 14th century BC, which in turn borrowed principles of representing phonetic information from Egyptian hieroglyphs.

situated above main entrance doors of Thomas Jefferson Building , Washington D.C.