Written Chinese

[2][3] This has led in part to the adoption of complementary transliteration systems (generally Pinyin)[4] as a means of representing the pronunciation of Chinese.

Xu did not have access to the earliest forms of Chinese characters, and his analysis is not considered to fully capture the nature of the writing system.

[16] (These principles, though popularized by the Shuowen Jiezi, were developed earlier; the oldest known mention of them is in the Rites of Zhou, a text from c. 150 BCE.

Of these four, two construct characters from simpler parts:[16] The last two principles do not produce new written forms; they instead transfer new meanings to existing forms:[16] In contrast to the popular conception of written Chinese as ideographic, the vast majority of characters—about 95% of those in the Shuowen Jiezi—either reflect elements of pronunciation, or are logical aggregates.

The strokes of Chinese characters fall into eight main categories: "horizontal" ⟨一⟩, "vertical" ⟨丨⟩, "left-falling" ⟨丿⟩, "right-falling" ⟨丶⟩, "rising", "dot" ⟨、⟩, "hook" ⟨亅⟩, and "turning" ⟨乛⟩, ⟨乚⟩, ⟨乙⟩.

Prior to the 20th century, Literary Chinese used little to no punctuation, with the breaks between sentences and phrases determined largely by context and the rhythms implied by patterns of syllables.

[22] In the 20th century, the layout used in Western scripts—where text is written in rows from left to right, which are laid out from top to bottom—became predominant in mainland China, where it was mandated by the Chinese government in 1955.

In general, punctuation occupies the width of a full character, such that text remains visually well-aligned in a grid.

Punctuation used in simplified Chinese shows clear influence from that used in Western scripts, though some marks are particular to Asian languages.

A special mark called an enumeration comma (、) is used to separate items in a list, as opposed to the clauses in a sentence.

[26] The earliest examples universally accepted as Chinese writing are the oracle bone inscriptions made during the reign of the Shang king Wu Ding (c. 1250 – c. 1192 BCE).

These inscriptions were made primarily on ox scapulae and turtle shells in order to record the results of divinations conducted by the Shang royal family.

[27] In 2003, 11 isolated symbols carved on tortoise shells were found at the Jiahu archaeological site in Henan—with some bearing a striking resemblance to certain modern characters, such as 目 (mù; 'eye').

Garman Harbottle, who had headed a team of archaeologists at the University of Science and Technology of China in Anhui—has suggested that these symbols were precursors to Chinese writing.

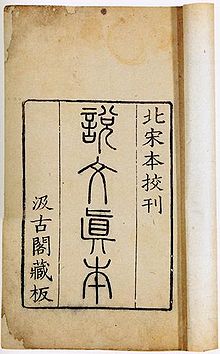

Li Si promulgated the seal script as the standard throughout China, which had been recently united under the imperial Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE).

[10] The initial adaptation of seal into clerical script can be attributed to scribes in the state of Qin working prior to the wars of unification.

[42][43] Once learned, it was a common medium for communication between people speaking different dialects, many of which were mutually unintelligible by the end of the first millennium CE.

[47] While some written vernacular Chinese expressions are often ungrammatical or unidiomatic outside of Mandarin, its use permits some communication between speakers of different dialects.

For literate speakers, it serves as a common medium; however, the forms of individual characters generally provide little insight to their meaning if not already known.

However, Taiwan's Ministry of Education has promulgated a standard character set for Hokkien, which is taught in schools and encouraged for use by the general population.

These roots, or radicals, generally but imperfectly align with the parts used to compose characters by means of logical aggregation and phonetic complex.

For instance, it is common for a dictionary ordered principally by the Kangxi radicals to have an auxiliary index by pronunciation, expressed typically in either pinyin or bopomofo.

The availability of computerized Chinese dictionaries now makes it possible to look characters up by any of the indexing schemes described, thereby shortening the search process.

The replacement of Chinese characters with a phonetic writing system was first prominently proposed during the May Fourth Movement, partly motivated by a desire to increase the country's literacy rate.

The idea gained further support following the victory of the Communists in 1949, who immediately began two parallel programs regarding written Chinese.

The first was the development of an alphabet to write the sounds of Mandarin, the variety spoken by around two-thirds of the Chinese population.

The Hanyu Pinyin (or simply 'pinyin') alphabet had been developed, but plans to replace Chinese characters with it were deferred, and the idea is no longer actively pursued.

While pinyin has become the predominant transliteration system for Mandarin, others include bopomofo, Wade–Giles, Yale, EFEO and Gwoyeu Romatzyh.