Japanese aesthetics

Thus, while seen as a philosophy in Western societies, the concept of aesthetics in Japan is seen as an integral part of daily life.

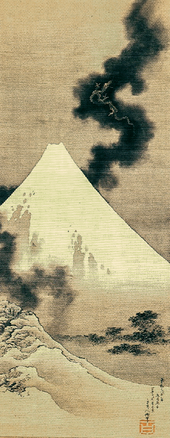

[3] With its emphasis on the wholeness of nature and character in ethics, and its celebration of the landscape, it sets the tone for Japanese aesthetics.

Over time their meanings overlapped and converged until they were unified into wabi-sabi, the aesthetic defined as the beauty of things "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete".

The signatures of nature can be so subtle that it takes a quiet mind and a cultivated eye to discern them.

[7] Fukinsei (不均斉): asymmetry, irregularity; Kanso (簡素): simplicity; Koko (考古): basic, weathered; Shizen (自然): without pretense, natural as a human behaviour; Yūgen (幽玄): subtly profound grace, not obvious; Datsuzoku (脱俗): unbounded by convention, free; Seijaku (静寂): tranquility, silence.

[8] Miyabi (雅) is one of the oldest of the traditional Japanese aesthetic ideals, though perhaps not as prevalent as Iki or Wabi-sabi.

Like other Japanese aesthetic terms, such as iki and wabi-sabi, shibui can apply to a wide variety of subjects, not just art or fashion.

Shibui objects appear to be simple overall but they include subtle details, such as textures, that balance simplicity with complexity.

This balance of simplicity and complexity ensures that one does not tire of a shibui object but constantly finds new meanings and enriched beauty that cause its aesthetic value to grow over the years.

Shibusa walks a fine line between contrasting aesthetic concepts such as elegant and rough or spontaneous and restrained.

The basis of iki is thought to have formed among the urbane mercantile class (Chōnin) in Edo in the Tokugawa period (1603–1868).

The phrase iki is generally used in Japanese culture to describe qualities that are aesthetically appealing and when applied to a person, what they do, or have, constitutes a high compliment.

While similar to wabi-sabi in that it disregards perfection, iki is a broad term that encompasses various characteristics related to refinement with flair.

[9] Jo-ha-kyū (序破急) is a concept of modulation and movement applied in a wide variety of traditional Japanese arts.

According to Zeami Motokiyo, all of the following are portals to yūgen: "To watch the sun sink behind a flower-clad hill.

[8] To introduce discipline into their training, Japanese warriors followed the example of the arts that systematized practice through prescribed forms called kata—think of the tea ceremony.

Zen Buddhist calligraphists may "believe that the character of the artist is fully exposed in how she or he draws an ensō.

In her pathmaking book,[13] Eiko Ikegami reveals a complex history of social life in which aesthetic ideals become central to Japan's cultural identities.

Therefore, recent interpretations of the aesthetics ideals inevitably reflect Judeo-Christian perspectives and Western philosophy.

[14] As one contribution to the broad subject of Japanese aesthetics and technology, it has been suggested that carefully curated high speed camera photographs of fluid dynamics events are able to capture the beauty of this natural phenomenon in a characteristically Japanese manner.

Enso c. 2000