Yadav

Yadavs are a grouping of non-elite,[1] peasant-pastoral[2] communities or castes in India that since the 19th and 20th centuries[3][4] have claimed descent from the legendary king Yadu as a part of a movement of social and political resurgence.

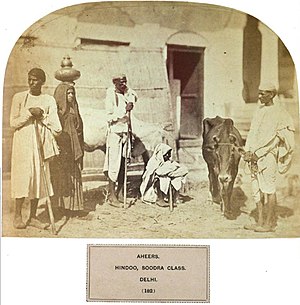

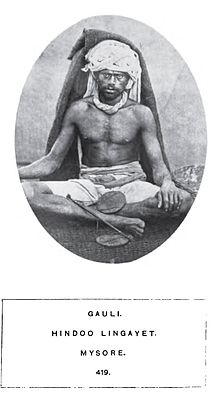

[20]Historians such as P. M. Chandorkar have used epigraphical and similar evidence to argue that Ahirs and Gavlis are representative of the ancient Yadavas and Abhiras mentioned in Sanskrit works.

Christophe Jaffrelot has remarked that The term 'Yadav' covers many castes which initially had different names: Ahir in the Hindi belt, Punjab and Gujarat, Gavli in Maharashtra, Golla in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka etc.

This descent-based kinship structure was also linked to a specific Kshatriya and their religious tradition centred on Krishna mythology and pastoral warrior hero-god cults.

[43] Although the Yadavs have formed a fairly significant proportion of the population in various areas, including 11% of that of Bihar in 1931, their interest in pastoral activities was not traditionally matched by ownership of land and consequently they were not a "dominant caste".

Since such communal lands were mostly appropriated by village landlords, the caste occupation of Yadavs brought them in conflict with latter, and such skirmishes gave a militant and aggressive edge to the community's character.

The attempt to move up in the social ladder also remained evident in the nature of community and in due course of time "thriftiness" was observed to be a phenomenon, where they tried to save and buy small plot of lands, to be classified as owner cultivators.

[48] Jaffrelot believes that the religious connotations of their connections to the cow and Krishna were seized upon by those Yadavs seeking to further the process of Sanskritisation,[40] and that it was Rao Bahadur Balbir Singh, a descendant of the last Abhira dynasty to be formed in India, who spearheaded this.

It had some success, notably in breaking down some of the very strict traditions of endogamy within the community, and it gained some additional momentum as people from rural areas gradually migrated away from their villages to urban centres such as Delhi.

[50] Of particular significance in the movement for Sanskritisation of the community was the role of the Arya Samaj, whose representatives had been involved with the family of Singh since the late 1890s and who had been able to establish branches in various locations.

He contrasts this "subversion" theory with the Nair's motive of "emancipation", whereby Sanskritisation was "a means of reconciling low ritual status with growing socio-economic assertiveness and of taking the first steps towards an alternative, Dravidian identity".

Using examples from Bihar, Jaffrelot demonstrates that there were some organised attempts among members of the Yadav community where the driving force was clearly secular and in that respect similar to the Nair's socio-economic movement.

These were based on a desire to end oppression caused by, for example, having to perform begari (forced labour) for upper castes and having to sell produce at prices below those prevailing in the open market to the zamindars, as well as by promoting education of the Yadav community.

[51] In support of the argument that the movements bore similarity, Jaffrelot cites Hetukar Jha, who says of the Bihar situation that "The real motive behind the attempts of the Yadavas, Kurmis and Koeris at Sanskritising themselves was to get rid of this socio-economic repression".

[38] In creating this history there is some support for an argument that Yadavs were looking to adopt an ethnic identity akin to the Dravidian one that was central to the Sanskritisation of the Nairs and other in south India.

They did acknowledge groups such as the Jats and Marathas as being similarly descended from Krishna but they did not particularly accommodate them in their adopted Aryan ethnic ideology, believing themselves to be superior to these other communities.

She argues that the perceived common link to Krishna was used to campaign for the official recognition of the many and varied herding communities of India under the title of Yadav, rather than merely as a means to claim the rank of Kshatriya.

Furthermore, that "... social leaders and politicians soon realised that their 'number' and the official proof of their demographic status were important political instruments on the basis of which they could claim a 'reasonable' share of state resources.

Furthermore, the AIYM encouraged the more wealthy members of the community to donate to good causes, such as for the funding of scholarships, temples, educational institutions and intra-community communications.

Aside from an inability to counter the superior organisational ability of the higher castes who opposed it, the unwillingness of the Yadavs to renounce their belief that they were natural leaders and that the Kurmi were somehow inferior was a significant factor in the lack of success.

[55] In the post-colonial period, according to Michelutti, it was the process of yadavisation and the concentration on two core aims – increasing the demographic coverage and campaigning for improved protection under the positive discrimination scheme for Backward Classes – that has been a singular feature of the AIYM, although it continues its work in other areas such as promotion of vegetarianism and teetotalism.

Well-reported bravery during fighting in the Himalayas in 1962, notably by the 13th Kumaon company of Ahirs, led to a campaign by the AIYM demanding the creation of a specific Yadav regiment.

[52] Mandelbaum has commented on how the community basks in the reflected glory of those members who achieve success, that "Yadav publications proudly cite not only their mythical progenitors and their historical Rajas, but also contemporaries who have become learned scholars, rich industrialists, and high civil servants."