Love

Love encompasses a range of strong and positive emotional and mental states, from the most sublime virtue or good habit, or the deepest interpersonal affection, to the simplest pleasure.

[3] In its various forms, love acts as a major facilitator of interpersonal relationships, and owing to its central psychological importance, is one of the most common themes in the creative arts.

This diversity of uses and meanings, combined with the complexity of the feelings involved, makes love unusually difficult to consistently define, compared to other emotional states.

[20] Helen Fisher, an anthropologist and human behavior researcher, divides the experience of love into three partly overlapping stages: lust, attraction, and attachment.

Recent studies in neuroscience have indicated that as people fall in love, the brain consistently releases a certain set of chemicals, including the neurotransmitter hormones dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, the same compounds released by amphetamine, stimulating the brain's pleasure center and leading to side effects such as increased heart rate, reduced appetite and sleep, and an intense feeling of excitement.

[citation needed] Another factor may be that sexually transmitted diseases can cause, among other effects, permanently reduced fertility, injury to the fetus, and increase complications during childbirth.

[30] Breakups can evoke a range of emotional states, including distrust, rejection, and anger, leading to trauma and various psychological challenges such as anxiety, social withdrawal, and even love addiction.

[34] In Latin, friendship was distinctly termed amicitia, while amor encompassed erotic passion, familial attachment, and, albeit less commonly, the affection between friends.

Cicero, in his essay On Friendship reflects on the innate human tendency to both love oneself and seek out another with whom to intertwine minds, nearly blending them into a singular entity.

Mozi contended that universal love was not merely an abstract concept but a practical imperative, requiring individuals to actively promote the welfare of all members of society through their actions.

Mozi's advocacy for universal love extended beyond interpersonal relationships; he believed it should guide the selection of rulers and the structuring of society, emphasizing reciprocity and egalitarianism as foundational principles for a harmonious social order.

[42] The Japanese language uses three words to convey the English equivalent of love — ai (愛), koi (恋 or 孤悲) and ren'ai (恋愛).

Initially synonymous with koi, representing romantic love between a man and a woman, emphasizing its physical expression, ai underwent a transformation during the early Meiji era.

Though modern usage of koi focuses on sexual love and infatuation, the Manyō used the term to cover a wider range of situations, including tenderness, benevolence, and material desire.

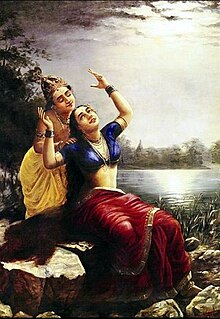

References in the Rigveda suggest the presence of romantic narratives in ancient Indo-Aryan society, evident in dialogues between deities like Yama and Yami, and Pururavas and Urvashi.

[45] Vatsalya originally signifies the tender affection exhibited by a cow towards her calf, extending to denote the love nurtured by elders or superiors towards the younger or inferior.

These interpretations emphasize Rumi's rejection of mortal attachments in favor of a love for the ultimate beloved, seen as embodying absolute beauty and grandeur.

Leonard Lewisohn characterizes Rumi's poetry as part of a mystical tradition that celebrates love as pathways to union with the divine, highlighting a transcendent experience.

Scholars such as Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob trace this philosophical stance, highlighting its fusion with ancient Persian religious beliefs in figures like Ibn Arabi.

This perspective is evident in the poetry of Hafez and others, where the concept of tajalli, or divine self-manifestation, underscores the profound spiritual significance of love as it pertains to both human relationships and devotion to God.

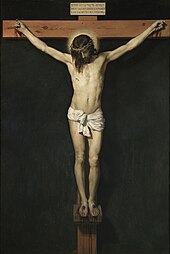

The Torah serves as a guide, outlining how Israelites should express their love for God, show reverence for nature, and demonstrate compassion toward fellow human beings.

The saints of Sufism are infamous for being "drunk" due to their love of God; hence, the constant reference to wine in Sufi poetry and music.

This perspective grounds adherence to law within the spiritual dynamics of each individual's journey, portraying obedience as a conscious choice driven by love rather than as mere compliance with external dictates.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Bahá'u'lláh's son and successor, describes love as the "most great law" and the force that binds together the diverse elements of the material world.

Loving-kindness, the first of the four, fosters goodwill toward all beings and leads naturally to compassion for those who suffer, joy in others' achievements, and, ultimately, to equanimity, a balanced state free from attachment and aversion.

This progression helps practitioners to reduce negative tendencies like ill-will, jealousy, and possessiveness, with the ultimate aim of cultivating inner peace and a compassionate view toward all beings, supporting both personal growth and societal harmony.

Together, these qualities encourage impartial love and empathy, fostering personal peace and societal harmony, and supporting both individual growth and a more compassionate world.

Gaudiya Vaishnavas consider that Krishna-prema (love for Godhead) burns away one's material desires, pierces the heart, and washes away everything—one's pride, one's religious rules, and one's shyness.

[70] Advocates of free love had two strong beliefs: opposition to the idea of forceful sexual activity in a relationship and advocacy for a woman to use her body in any way that she pleases.

Figures like Annette Baier and Neera K. Badhwar highlight emotional interdependence, though critics wonder how this distinguishes love from other relationships and defines its unique narrative.