Accelerating expansion of the universe

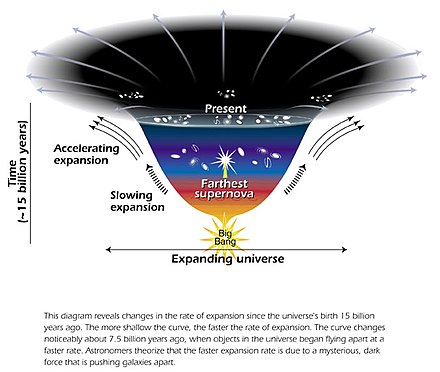

Cosmologists at the time expected that recession velocity would always be decelerating, due to the gravitational attraction of the matter in the universe.

[11] Each of the components decreases with the expansion of the universe (increasing scale factor), except perhaps the dark energy term.

The acceleration equation describes the evolution of the scale factor with time where the pressure P is defined by the cosmological model chosen.

According to the theory of cosmic inflation, the very early universe underwent a period of very rapid, quasi-exponential expansion.

Also a factor is the growth of large-scale structure, finding that the observed values of the cosmological parameters are best described by models which include an accelerating expansion.

In 1998, the first evidence for acceleration came from the observation of Type Ia supernovae, which are exploding white dwarf stars that have exceeded their stability limit.

For supernovae at redshift less than around 0.1, or light travel time less than 10 percent of the age of the universe, this gives a nearly linear distance–redshift relation due to Hubble's law.

The full calculation requires computer integration of the Friedmann equation, but a simple derivation can be given as follows: the redshift z directly gives the cosmic scale factor at the time the supernova exploded.

Adam Riess et al. found that "the distances of the high-redshift SNe Ia were, on average, 10% to 15% further than expected in a low mass density ΩM = 0.2 universe without a cosmological constant".

[15] Several researchers have questioned the majority opinion on the acceleration or the assumption of the "cosmological principle" (that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic).

In the early universe before recombination and decoupling took place, photons and matter existed in a primordial plasma.

Points of higher density in the photon-baryon plasma would contract, being compressed by gravity until the pressure became too large and they expanded again.

When decoupling occurred, approximately 380,000 years after the Big Bang,[19] photons separated from matter and were able to stream freely through the universe, creating the cosmic microwave background as we know it.

As time passed and the universe expanded, it was at these inhomogeneities of matter density where galaxies started to form.

Peaks have been found in the correlation function (the probability that two galaxies will be a certain distance apart) at 100 h−1 Mpc,[11] (where h is the dimensionless Hubble constant) indicating that this is the size of the sound horizon today, and by comparing this to the sound horizon at the time of decoupling (using the CMB), we can confirm the accelerated expansion of the universe.

By comparing this to actual measured values of the cosmological parameters, we can confirm the validity of a model which is accelerating now, and had a slower expansion in the past.

[15] Recent discoveries of gravitational waves through LIGO and VIRGO[22][23][24] not only confirmed Einstein's predictions but also opened a new window into the universe.

These gravitational waves can work as sort of standard sirens to measure the expansion rate of the universe.

[25][24] The most important property of dark energy is that it has negative pressure (repulsive action) which is distributed relatively homogeneously in space.

Riess et al. found that their results from supernova observations favoured expanding models with positive cosmological constant (Ωλ > 0) and an accelerated expansion (q0 < 0).

This phantom energy density would become infinite in finite time, causing such a huge gravitational repulsion that the universe would lose all structure and end in a Big Rip.

[26] For example, for w = −3/2 and H0 =70 km·s−1·Mpc−1, the time remaining before the universe ends in this Big Rip is 22 billion years.

Some examples are quintessence, a proposed form of dark energy with a non-constant state equation, whose density decreases with time.

According to general relativity, space is less curved than on the walls, and thus appears to have more volume and a higher expansion rate.

For example, if we are located in an emptier-than-average region of space, the observed cosmic expansion rate could be mistaken for a variation in time, or acceleration.

[42][43][44][45] A different approach uses a cosmological extension of the equivalence principle to show how space might appear to be expanding more rapidly in the voids surrounding our local cluster.

While weak, such effects considered cumulatively over billions of years could become significant, creating the illusion of cosmic acceleration, and making it appear as if we live in a Hubble bubble.

This will eventually lead to all evidence for the Big Bang disappearing, as the cosmic microwave background is redshifted to lower intensities and longer wavelengths.

Eventually, its frequency will be low enough that it will be absorbed by the interstellar medium, and so be screened from any observer within the galaxy.

Under such a scenario, it is understood that all matter will ionize and disintegrate into isolated stable particles such as electrons and neutrinos, with all complex structures dissipating.