Activation energy

The term "activation energy" was introduced in 1889 by the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius.

[3] Although less commonly used, activation energy also applies to nuclear reactions[4] and various other physical phenomena.

[5][6][7] The Arrhenius equation gives the quantitative basis of the relationship between the activation energy and the rate at which a reaction proceeds.

Even without knowing A, Ea can be evaluated from the variation in reaction rate coefficients as a function of temperature (within the validity of the Arrhenius equation).

There are two objections to associating this activation energy with the threshold barrier for an elementary reaction.

Second, even if the reaction being studied is elementary, a spectrum of individual collisions contributes to rate constants obtained from bulk ('bulb') experiments involving billions of molecules, with many different reactant collision geometries and angles, different translational and (possibly) vibrational energies—all of which may lead to different microscopic reaction rates.

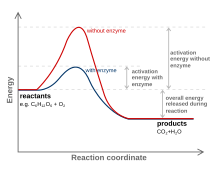

[citation needed] A substance that modifies the transition state to lower the activation energy is termed a catalyst; a catalyst composed only of protein and (if applicable) small molecule cofactors is termed an enzyme.

A catalyst is able to reduce the activation energy by forming a transition state in a more favorable manner.

Catalysts, by nature, create a more "comfortable" fit for the substrate of a reaction to progress to a transition state.

This is possible due to a release of energy that occurs when the substrate binds to the active site of a catalyst.

Specific and favorable bonding occurs within the active site until the substrate forms to become the high-energy transition state.

A chemical reaction is able to manufacture a high-energy transition state molecule more readily when there is a stabilizing fit within the active site of a catalyst.

Reactions without catalysts need a higher input of energy to achieve the transition state.

In transition state theory, a more sophisticated model of the relationship between reaction rates and the transition state, a superficially similar mathematical relationship, the Eyring equation, is used to describe the rate constant of a reaction: k = (kBT / h) exp(−ΔG‡ / RT).

Although the equations look similar, it is important to note that the Gibbs energy contains an entropic term in addition to the enthalpic one.

Then, for a unimolecular, one-step reaction, the approximate relationships Ea = ΔH‡ + RT and A = (kBT/h) exp(1 + ΔS‡/R) hold.

This is also the roughly the magnitude of Ea for a reaction that proceeds over several hours at room temperature.

Due to the relatively small magnitude of TΔS‡ and RT at ordinary temperatures for most reactions, in sloppy discourse, Ea, ΔG‡, and ΔH‡ are often conflated and all referred to as the "activation energy".

The enthalpy, entropy and Gibbs energy of activation are more correctly written as Δ‡Ho, Δ‡So and Δ‡Go respectively, where the o indicates a quantity evaluated between standard states.

When following an approximately exponential relationship so the rate constant can still be fit to an Arrhenius expression, this results in a negative value of Ea.

Increasing the temperature leads to a reduced probability of the colliding molecules capturing one another (with more glancing collisions not leading to reaction as the higher momentum carries the colliding particles out of the potential well), expressed as a reaction cross section that decreases with increasing temperature.

Certain cationic polymerization reactions have negative activation energies so that the rate decreases with temperature.