Transition state theory

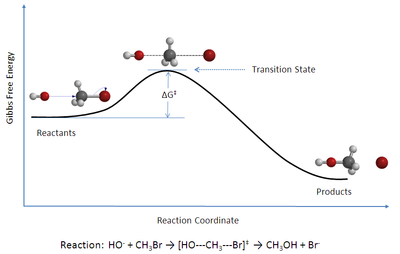

The theory assumes a special type of chemical equilibrium (quasi-equilibrium) between reactants and activated transition state complexes.

TST has been less successful in its original goal of calculating absolute reaction rate constants because the calculation of absolute reaction rates requires precise knowledge of potential energy surfaces,[2] but it has been successful in calculating the standard enthalpy of activation (ΔH‡, also written Δ‡Hɵ), the standard entropy of activation (ΔS‡ or Δ‡Sɵ), and the standard Gibbs energy of activation (ΔG‡ or Δ‡Gɵ) for a particular reaction if its rate constant has been experimentally determined (the ‡ notation refers to the value of interest at the transition state; ΔH‡ is the difference between the enthalpy of the transition state and that of the reactants).

The Arrhenius equation derives from empirical observations and ignores any mechanistic considerations, such as whether one or more reactive intermediates are involved in the conversion of a reactant to a product.

[citation needed] In 1910, French chemist René Marcelin introduced the concept of standard Gibbs energy of activation.

His relation can be written as At about the same time as Marcelin was working on his formulation, Dutch chemists Philip Abraham Kohnstamm, Frans Eppo Cornelis Scheffer, and Wiedold Frans Brandsma introduced standard entropy of activation and the standard enthalpy of activation.

However, the application of statistical mechanics to TST was developed very slowly given the fact that in mid-19th century, James Clerk Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann, and Leopold Pfaundler published several papers discussing reaction equilibrium and rates in terms of molecular motions and the statistical distribution of molecular speeds.

Two years later, René Marcelin made an essential contribution by treating the progress of a chemical reaction as a motion of a point in phase space.

He theorized that the progress of a chemical reaction could be described as a point in a potential energy surface with coordinates in atomic momenta and distances.

This surface is a three-dimensional diagram based on quantum-mechanical principles as well as experimental data on vibrational frequencies and energies of dissociation.

A year after the Eyring and Polanyi construction, Hans Pelzer and Eugene Wigner made an important contribution by following the progress of a reaction on a potential energy surface.

The importance of this work was that it was the first time that the concept of col or saddle point in the potential energy surface was discussed.

[11] One of the most important features introduced by Eyring, Polanyi and Evans was the notion that activated complexes are in quasi-equilibrium with the reactants.

However, the key statistical mechanical factor kBT/h will not be justified, and the argument presented below does not constitute a true "derivation" of the Eyring equation.

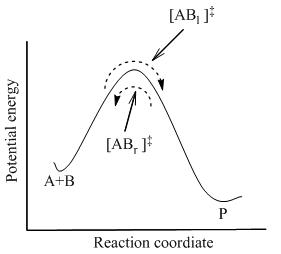

As illustrated in Figure 2, at any instant of time, there are a few activated complexes, and some were reactant molecules in the immediate past, which are designated [ABl]‡ (since they are moving from left to right).

These so-called activation parameters give insight into the nature of a transition state, including energy content and degree of order, compared to the starting materials and has become a standard tool for elucidation of reaction mechanisms in physical organic chemistry.

However, the Arrhenius equation was derived from experimental data and models the macroscopic rate using only two parameters, irrespective of the number of transition states in a mechanism.

The entropy of activation, ΔS‡, gives the extent to which transition state (including any solvent molecules involved in or perturbed by the reaction) is more disordered compared to the starting materials.

[16] The volume of activation is found by taking the partial derivative of ΔG‡ with respect to pressure (holding temperature constant):

For comparison, the cyclohexane chair flip has a ΔG‡ of about 11 kcal/mol with k ~ 105 s−1, making it a dynamic process that takes place rapidly (faster than the NMR timescale) at room temperature.

At the other end of the scale, the cis/trans isomerization of 2-butene has a ΔG‡ of about 60 kcal/mol, corresponding to k ~ 10−31 s−1 at 298 K. This is a negligible rate: the half-life is 12 orders of magnitude longer than the age of the universe.

[18] In general, TST has provided researchers with a conceptual foundation for understanding how chemical reactions take place.

[19] In such cases, the momentum of the reaction trajectory from the reactants to the intermediate can carry forward to affect product selectivity.

To correct for this, variational transition state theory varies the location of the dividing surface that defines a successful reaction in order to minimize the rate for each fixed energy.

A development of transition state theory in which the position of the dividing surface is varied so as to minimize the rate constant at a given temperature.

A compromise dividing surface is then chosen so as to minimize the contributions to the rate constant made by reactants having higher energies.

An expansion of TST to the reactions when two spin-states are involved simultaneously is called nonadiabatic transition state theory (NA-TST).

Each catalytic event requires a minimum of three or often more steps, all of which occur within the few milliseconds that characterize typical enzymatic reactions.

Soon thereafter, Linus Pauling proposed that the powerful catalytic action of enzymes could be explained by specific tight binding to the transition state species [26] Because reaction rate is proportional to the fraction of the reactant in the transition state complex, the enzyme was proposed to increase the concentration of the reactive species.

The transition states for chemical reactions are proposed to have lifetimes near 10−13 seconds, on the order of the time of a single bond vibration.

No physical or spectroscopic method is available to directly observe the structure of the transition state for enzymatic reactions, yet transition state structure is central to understanding enzyme catalysis since enzymes work by lowering the activation energy of a chemical transformation.