Aldol reaction

[8][9] The reaction is well used on an industrial scale, notably of pentaerythritol,[10] trimethylolpropane, the plasticizer precursor 2-ethylhexanol, and the drug Lipitor (atorvastatin, calcium salt).

[11] For many of the commodity applications, the stereochemistry of the aldol reaction is unimportant, but the topic is of intense interest for the synthesis of many specialty chemicals.

Complicated mixtures from cross aldol reactions can be avoided by using one component that cannot form an enolate, examples being formaldehyde and benzaldehyde.

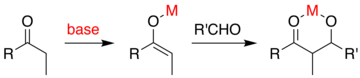

If the base is of only moderate strength such as hydroxide ion or an alkoxide, the aldol reaction occurs via nucleophilic attack by the resonance-stabilized enolate on the carbonyl group of another molecule.

When an acid catalyst is used, the initial step in the reaction mechanism involves acid-catalyzed tautomerization of the carbonyl compound to the enol.

The enol is nucleophilic at the α-carbon, allowing it to attack the protonated carbonyl compound, leading to the aldol after deprotonation.

[13] If the conditions are particularly harsh (e.g.: NaOMe/MeOH/reflux), condensation may occur, but this can usually be avoided with mild reagents and low temperatures (e.g., LDA (a strong base), THF, −78 °C).

Thus cross-aldehyde reactions are typically most challenging because they can polymerize easily or react unselectively to give a statistical mixture of products.

Common kinetic control conditions involve the formation of the enolate of a ketone with LDA at −78 °C, followed by the slow addition of an aldehyde.

Modern methodology has not only developed high-yielding aldol reactions, but also completely controls both the relative and absolute configuration of these new stereocenters.

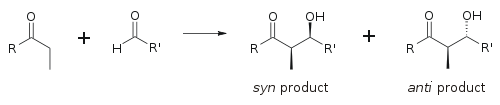

The disposition of the formed stereocenters is deemed syn or anti, depending if they are on the same or opposite sides of the main chain: The principal factor determining an aldol reaction's stereoselectivity is the enolizing metal counterion.

Since the transition state for Z enolates must contain either a destabilizing syn-pentane interaction or an anti-Felkin rotamer, Z-enolates are less diastereoselective:[27][28] If both the enolate and the aldehyde contain pre-existing chirality, then the outcome of the "double stereodifferentiating" aldol reaction may be predicted using a merged stereochemical model that takes into account all the effects discussed above.

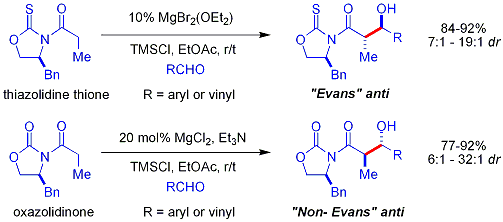

[29] Several examples are as follows:[28] In the late 1970s and 1980s, David A. Evans and coworkers developed a technique for stereoselection in the aldol syntheses of aldehydes and carboxylic acids.

Commercial oxazolidinones are relatively expensive, but derive in 2 synthetic steps from comparatively inexpensive amino acids.

There is no danger of an achiral background reaction because the transient enamine intermediates are much more nucleophilic than their parent ketone enols.

A superior method, in principle, would avoid the requirement for a multistep sequence in favor of a "direct" reaction that could be done in a single process step.

If one coupling partner preferentially enolizes, then the general problem is that the addition generates an alkoxide, which is much more basic than the starting materials.

This product binds tightly to the enolizing agent, preventing it from catalyzing additional reactants: One approach, demonstrated by Evans, is to silylate the aldol adduct.

[45][46] A silicon reagent such as TMSCl is added in the reaction, which replaces the metal on the alkoxide, allowing turnover of the metal catalyst: Traditional syntheses of hexoses use variations of iterative protection-deprotection strategies, requiring 8–14 steps, organocatalysis can access many of the same substrates by a two-step protocol involving the proline-catalyzed dimerization of alpha-oxyaldehydes followed by tandem Mukaiyama aldol cyclization.

The protected erythrose product could then be converted to four possible sugars via Mukaiyama aldol addition followed by lactol formation.

In the end, glucose, mannose, and allose were synthesized: Examples of aldol reactions in biochemistry include the splitting of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate into dihydroxyacetone and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate in the fourth stage of glycolysis, which is an example of a reverse ("retro") aldol reaction catalyzed by the enzyme aldolase A (also known as fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase).

The flask on the right is a solution of lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) in tetrahydrofuran (THF). The flask on the left is a solution of the lithium enolate of tert -butyl propionate (formed by addition of LDA to tert -butyl propionate). An aldehyde can then be added to the enolate flask to initiate an aldol addition reaction.

Both flasks are submerged in a dry ice/acetone cooling bath (−78 °C) the temperature of which is being monitored by a thermocouple (the wire on the left).