Alloy

Most alloys are metallic and show good electrical conductivity, ductility, opacity, and luster, and may have properties that differ from those of the pure elements such as increased strength or hardness.

[1] The alloy constituents are usually measured by mass percentage for practical applications, and in atomic fraction for basic science studies.

Adding a small amount of non-metallic carbon to iron trades its great ductility for the greater strength of an alloy called steel.

Due to its very-high strength, but still substantial toughness, and its ability to be greatly altered by heat treatment, steel is one of the most useful and common alloys in modern use.

[2] Lithium, sodium and calcium are common impurities in aluminium alloys, which can have adverse effects on the structural integrity of castings.

Great care is often taken during the alloying process to remove excess impurities, using fluxes, chemical additives, or other methods of extractive metallurgy.

This increases the chance of contamination from any contacting surface, and so must be melted in vacuum induction-heating and special, water-cooled, copper crucibles.

For example, impurities in semiconducting ferromagnetic alloys lead to different properties, as first predicted by White, Hogan, Suhl, Tian Abrie and Nakamura.

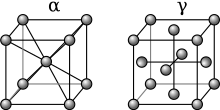

[8] The base metal iron of the iron-carbon alloy known as steel, undergoes a change in the arrangement (allotropy) of the atoms of its crystal matrix at a certain temperature (usually between 820 °C (1,500 °F) and 870 °C (1,600 °F), depending on carbon content).

If the steel is cooled quickly, however, the carbon atoms will not have time to diffuse and precipitate out as carbide, but will be trapped within the iron crystals.

When heated to form a solution and then cooled quickly, these alloys become much softer than normal, during the diffusionless transformation, but then harden as they age.

However, when Wilm retested it the next day he discovered that the alloy increased in hardness when left to age at room temperature, and far exceeded his expectations.

[9] Because they often exhibit a combination of high strength and low weight, these alloys became widely used in many forms of industry, including the construction of modern aircraft.

[13] Native copper, however, was found worldwide, along with silver, gold, and platinum, which were also used to make tools, jewelry, and other objects since Neolithic times.

[14] Ancient civilizations took into account the mixture and the various properties it produced, such as hardness, toughness and melting point, under various conditions of temperature and work hardening, developing much of the information contained in modern alloy phase diagrams.

[15] For example, arrowheads from the Chinese Qin dynasty (around 200 BC) were often constructed with a hard bronze-head, but a softer bronze-tang, combining the alloys to prevent both dulling and breaking during use.

[19] Around 250 BC, Archimedes was commissioned by the King of Syracuse to find a way to check the purity of the gold in a crown, leading to the famous bath-house shouting of "Eureka!"

[21] The alloy was also used in China and the Far East, arriving in Japan around 800 AD, where it was used for making objects like ceremonial vessels, tea canisters, or chalices used in shinto shrines.

These steels were of poor quality, and the introduction of pattern welding, around the 1st century AD, sought to balance the extreme properties of the alloys by laminating them, to create a tougher metal.

Around 700 AD, the Japanese began folding bloomery-steel and cast-iron in alternating layers to increase the strength of their swords, using clay fluxes to remove slag and impurities.

[15] While the use of iron started to become more widespread around 1200 BC, mainly because of interruptions in the trade routes for tin, the metal was much softer than bronze.

The ability to modify the hardness of steel by heat treatment had been known since 1100 BC, and the rare material was valued for the manufacture of tools and weapons.

Puddling had been used in China since the first century, and was introduced in Europe during the 1700s, where molten pig iron was stirred while exposed to the air, to remove the carbon by oxidation.

In 1858, Henry Bessemer developed a process of steel-making by blowing hot air through liquid pig iron to reduce the carbon content.

Since ancient times, when steel was used primarily for tools and weapons, the methods of producing and working the metal were often closely guarded secrets.

Even long after the Age of Enlightenment, the steel industry was very competitive and manufacturers went through great lengths to keep their processes confidential, resisting any attempts to scientifically analyze the material for fear it would reveal their methods.

For example, the people of Sheffield, a center of steel production in England, were known to routinely bar visitors and tourists from entering town to deter industrial espionage.

However, as extractive metallurgy was still in its infancy, most aluminium extraction-processes produced unintended alloys contaminated with other elements found in the ore; the most abundant of which was copper.

[30] During the time between 1865 and 1910, processes for extracting many other metals were discovered, such as chromium, vanadium, tungsten, iridium, cobalt, and molybdenum, and various alloys were developed.

[30] The Doehler Die Casting Co. of Toledo, Ohio were known for the production of Brastil, a high tensile corrosion resistant bronze alloy.