Alpha-synuclein

[17] It is expressed highly in neurons within the frontal cortex, hippocampus, striatum, and olfactory bulb,[17] but can also be found in the non-neuronal glial cells.

The unfolded amyloid CsgA, which is secreted by bacteria and later aggregates extracellularly to create biofilms, mediates adherence to epithelial cells, and aids in bacteriophage defense, forms the curli fibers.

Oral injection of curli-producing bacteria can also boost formation and aggregation of the amyloid protein Syn in old rats and nematodes.

Studies in biochemistry show that endogenous, bacterial chaperones of curli are capable of briefly interacting with Syn and controlling its aggregation.

[29] The clinical and pathological findings support the hypothesis that aSyn disease in PD occurs via a gut-brain pathway.

[30] As suggested by Borghammer and Van Den Berge (2019), one approach is to recognise the possibility of PD subtypes with various aSyn propagation methods, including either a peripheral nervous system (PNS)-first or a CNS-first route.

[34] Alpha-synuclein is specifically upregulated in a discrete population of presynaptic terminals of the brain during a period of acquisition-related synaptic rearrangement.

Knock-out mice with the targeted inactivation of the expression of alpha-synuclein show impaired spatial learning and working memory.

Yeast genome screening has found that several genes that deal with lipid metabolism and mitochondrial fusion play a role in alpha-synuclein toxicity.

[41][42] Conversely, alpha-synuclein expression levels can affect the viscosity and the relative amount of fatty acids in the lipid bilayer.

[45] The binding of alpha-synuclein to lipid membranes has complex effects on the latter, altering the bilayer structure and leading to the formation of small vesicles.

[50] The protein adopts a broken-helical conformation on lipoprotein particles while it forms an extended helical structure on lipid vesicles and membrane tubes.

[9] It may also help regulate the release of dopamine, a type of neurotransmitter that is critical for controlling the start and stop of voluntary and involuntary movements.

[68] DNA damage response markers co-localize with alpha-synuclein to form discrete foci in human cells and mouse brain.

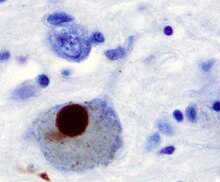

[68] The DNA repair function of alpha-synuclein appears to be compromised in Lewy body inclusion bearing neurons, and this may trigger cell death.

Recently it has been demonstrated that up-regulation of alpha-synuclein in the dentate gyrus (a neurogenic niche where new neurons are generated throughout life) activates stem cells, in a model of premature neural aging.

[70] Similarly, alpha-synuclein has been found to be required to maintain stem cells of the SVZ (subventricular zone, i.e., another neurogenic niche) in a cycling state.

Alpha synuclein, having no single, well-defined tertiary structure, is an intrinsically disordered protein,[77][78] with a pI value of 4.7,[79] which, under certain pathological conditions, can misfold in a way that exposes its core hydrophobic residues to the intracellular milieu, thus providing the opportunity for hydrophobic interactions to occur with a similar, equally exposed protein.

Proponents of the tetramer hypothesis argued that in vivo cross-linking in bacteria, primary neurons and human erythroleukemia cells confirmed the presence of labile, tetrameric species.

In vitro models of synucleinopathies revealed that aggregation of alpha-synuclein may lead to various cellular disorders including microtubule impairment, synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunctions, oxidative stress as well as dysregulation of Calcium signaling, proteasomal and lysosomal pathway.

[103] A single molecule study in 2008 suggests alpha-synuclein exists as a mix of unstructured, alpha-helix, and beta-sheet-rich conformers in equilibrium.

[114][115] Genomic duplication and triplication of the gene appear to be a rare cause of Parkinson's disease in other lineages, although more common than point mutations.

[118] Although the accumulation and aggregation of alpha-synuclein in most Parkinson's disease patients primarily result from posttranscriptional mechanisms, targeting its production remains a potential therapeutic approach.

From in vitro work, it is clear that unfolded monomer can aggregate first into small oligomeric species that can be stabilized by β-sheet-like interactions and then into higher molecular weight insoluble fibrils.

In a cellular context, there is some evidence that the presence of lipids can promote oligomer formation: α-synuclein can also form annular, pore-like structures that interact with membranes.

As well as phosphorylation, truncation through proteases such as calpains, and nitration, probably through nitric oxide (NO) or other reactive nitrogen species that are present during inflammation, all modify synuclein such that it has a higher tendency to aggregate.

On the right are some of the proposed cellular targets for α-synuclein mediated toxicity, which include (from top to bottom) ER-golgi transport, synaptic vesicles, mitochondria and lysosomes and other proteolytic machinery.

In each of these cases, it is proposed that α-synuclein has detrimental effects, listed below each arrow, although at this time it is not clear if any of these are either necessary or sufficient for toxicity in neurons.