Aluminium compounds

[1] Furthermore, as Al3+ is a small and highly charged cation, it is strongly polarizing and aluminium compounds tend towards covalency;[2] this behaviour is similar to that of beryllium (Be2+), an example of a diagonal relationship.

Aluminium's electropositive behavior, high affinity for oxygen, and highly negative standard electrode potential are all more similar to those of scandium, yttrium, lanthanum, and actinium, which have ds2 configurations of three valence electrons outside a noble gas core: aluminium is the most electropositive metal in its group.

It also forms a wide range of intermetallic compounds involving metals from every group on the periodic table.

Aluminium has a high chemical affinity to oxygen, which renders it suitable for use as a reducing agent in the thermite reaction.

A fine powder of aluminium reacts explosively on contact with liquid oxygen; under normal conditions, however, aluminium forms a thin oxide layer that protects the metal from further corrosion by oxygen, water, or dilute acid, a process termed passivation.

[2][6] This layer is destroyed by contact with mercury due to amalgamation or with salts of some electropositive metals.

[1] In addition, although the reaction of aluminium with water at temperatures below 280 °C is of interest for the production of hydrogen, commercial application of this fact has challenges in circumventing the passivating oxide layer, which inhibits the reaction, and in storing the energy required to regenerate the aluminium.

[9] However, because of its general resistance to corrosion, aluminium is one of the few metals that retains silvery reflectance in finely powdered form, making it an important component of silver-colored paints.

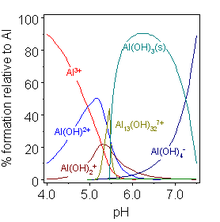

Aluminium hydroxide forms both salts and aluminates and dissolves in acid and alkali, as well as on fusion with acidic and basic oxides:[2] This behaviour of Al(OH)3 is termed amphoterism, and is characteristic of weakly basic cations that form insoluble hydroxides and whose hydrated species can also donate their protons.

Aluminium cyanide, acetate, and carbonate exist in aqueous solution but are unstable as such; only incomplete hydrolysis takes place for salts with strong acids, such as the halides, nitrate, and sulfate.

For similar reasons, anhydrous aluminium salts cannot be made by heating their "hydrates": hydrated aluminium chloride is in fact not AlCl3·6H2O but [Al(H2O)6]Cl3, and the Al–O bonds are so strong that heating is not sufficient to break them and form Al–Cl bonds instead:[2] All four trihalides are well known.

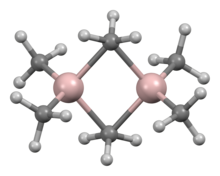

The aluminium trihalides form many addition compounds or complexes; their Lewis acidic nature makes them useful as catalysts for the Friedel–Crafts reactions.

[13] As corundum is very hard (Mohs hardness 9), has a high melting point of 2,045 °C (3,713 °F), has very low volatility, is chemically inert, and a good electrical insulator, it is often used in abrasives (such as toothpaste), as a refractory material, and in ceramics, as well as being the starting material for the electrolytic production of aluminium.

All three are prepared by direct reaction of their elements at about 1,000 °C (1,832 °F) and quickly hydrolyse completely in water to yield aluminium hydroxide and the respective hydrogen chalcogenide.

As aluminium is a small atom relative to these chalcogens, these have four-coordinate tetrahedral aluminium with various polymorphs having structures related to wurtzite, with two-thirds of the possible metal sites occupied either in an orderly (α) or random (β) fashion; the sulfide also has a γ form related to γ-alumina, and an unusual high-temperature hexagonal form where half the aluminium atoms have tetrahedral four-coordination and the other half have trigonal bipyramidal five-coordination.

AlF, AlCl, AlBr, and AlI exist in the gaseous phase when the respective trihalide is heated with aluminium, and at cryogenic temperatures.

For example, aluminium monoxide, AlO, has been detected in the gas phase after explosion[19] and in stellar absorption spectra.