Andaman Sea

Traditionally, the sea has been used for fishery and transportation of goods between the coastal countries and its coral reefs and islands are popular tourist destinations.

The Andaman Sea, which extends over 92°E to 100°E and 4°N to 20°N, occupies a very significant position in the Indian Ocean, yet remained unexplored for a long period.

The Strait of Malacca (between the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra) forms the southern exitway of the basin, which is 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) wide and 37 metres (121 ft) deep.

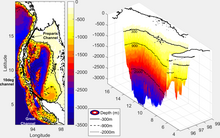

[6] Exclusive economic zones in Andaman Sea:[7] The northern and eastern side of the basin is shallow, as the continental shelf off the coast of Myanmar and Thailand extends over 200 kilometres (120 mi) (marked by 300 metres (980 ft) isobath).

About 45 percent of the basin area is shallower (less than 500 metres (1,600 ft) depth), which is the direct consequence of the presence of the wider shelf.

Here, the perspective view of the submarine topography sectioned along 95°E exposes the abrupt rise in depth of sea by about 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) within a short horizontal distance of a degree.

Further, it may be noted that the deep ocean is also not free from sea mounts; hence only around 15 percent of the total area is deeper than 2,500 metres (8,200 ft).

[8] The boundary between two major tectonic plates results in high seismic activity in the region (see List of earthquakes in Indonesia).

Between 1,300 and 1,600 kilometres (810 and 990 mi) of the boundary underwent thrust faulting and shifted by about 20 metres (66 ft), with the sea floor being uplifted several meters.

[9] This rise in the sea floor generated a massive tsunami with an estimated height of 28 meters (92 feet)[10] that killed approximately 280,000 people along the coast of the Indian Ocean.

Further, 2) There is no evidence showing that modern sediment has accumulated or is transported into the Martaban Canyon; 3) a mud drape/blanket is wrapping around the narrow western Myanmar Shelf in the eastern Bay of Bengal.

The thickness of the mud deposit is up to 20 metres (66 ft) nearshore and gradually thins to the slope at −300 metres (−980 ft) water depth, and likely escapes into the deep Andaman Trench; 4) The estimated total amount of Holocene sediments deposited offshore is approximately 1,290 by 109 tonnes (1,270 by 107 long tons; 1,422 by 120 short tons).

If we assume this has mainly accumulated since the middle Holocene highstand (~6000 yr BP) like other major deltas, the historical annual mean depositional flux on the shelf would be 215 megatonnes (212,000,000 long tons; 237,000,000 short tons) per year, which is equivalent to ~35% of the modern Ayeyarwady-Thanlwin rivers derived sediments; 5) Unlike other large river systems in Asia, such as the Yangtze and Mekong, this study indicates a bi-directional transport and depositional pattern controlled by the local currents that are influenced by tides, and seasonally varying monsoons winds and waves.

[16] The climate of the Andaman Sea is determined by the monsoons of southeast Asia,[3] as the prevailing winds reverse with the start of either season.

It weakens by March–April and reverses to strong south-westerlies from May to September, with mean wind speeds touching 8 m/s (29 km/h) in June, July, and August, distributed near-uniformly over the entire basin.

[3] The contrast between the two seasons elicits a very strong negative pumping velocity of more than 5 m (16 ft) per day along the north coast of Indonesia from May to September (shown here, June).

It is also observed that the region develops a weak but positive pumping velocity of less than 3 m (9.8 ft) per day at the mouth of GC in winter (here, December).

During April and October, when the effects of local winds are minimal, Andaman Sea experiences the intensification of meridional surface currents in the poleward direction along the continental slope on the eastern side of the basin.

(Previous studies[18] show that the annual mean freshwater gain (precipitation minus evaporation) of the Andaman Sea is 120 centimetres (47 in) per year.)

These Kelvin waves are guided along the eastern boundary of Indian Ocean, and a part of this signal propagates into the Andaman Sea.

The waves further propagate along the eastern boundary of the Andaman Sea, which is confirmed by the differential deepening of the 20-degree isotherm along longitudes 94°E and 97°E (averaged over latitudes 8°N and 13°N).

This confirms unequivocally that the sudden burst of water into the basin through the straits, the intensification of eastern boundary currents and the coincidental deepening of isotherms in April and October are the direct consequence of the propagation of downwelling Kelvin waves in the Andaman Sea, remotely forced by equatorial Wyrtki jets.

[12]: 25–26 Mangroves are largely responsible for the high productivity of the coastal waters – their roots trap soil and sediment and provide shelter from predators and nursery for fish and small aquatic organisms.

A significant part of the Thai mangrove forests in the Andaman Sea was removed during the extensive brackish water shrimp farming in 1980s[citation needed].

[12]: 6–7 Other important sources of nutrients in the Andaman Sea are seagrass and the mud bottoms of lagoons and coastal areas.

The 2004 tsunami affected 3.5% of seagrass areas along the Andaman Sea via siltation and sand sedimentation and 1.5% suffered total habitat loss.

[12]: 7 The sea waters along the Malay Peninsula favor molluscan growth, and there are about 280 edible fish species belonging to 75 families.

The main mollusk species captured in the Andaman Sea are scallop, blood cockle (Anadara granosa) and short-necked clam.

[24] The nearby coast also has numerous marine national parks – 16 only in Thailand, and four of them are candidates for inclusion into UNESCO World Heritage Sites.