Gospel of Luke

[6] The combined work divides the history of first-century Christianity into three stages, with the gospel making up the first two of these – the life of Jesus the messiah (Christ) from his birth to the beginning of his mission in the meeting with John the Baptist, followed by his ministry with events such as the Sermon on the Plain and its Beatitudes, and his Passion, death, and resurrection.

[5] Together they account for 27.5% of the New Testament, the largest contribution by a single author, providing the framework for both the Church's liturgical calendar and the historical outline into which later generations have fitted their idea of the story of Jesus.

[6] The author is not named in either volume,[8] but he was educated, a man of means, probably urban, and someone who respected manual work, although not a worker himself; this is significant, because more high-brow writers of the time looked down on the artisans and small business-people who made up the early church of Paul and who were presumably Luke's audience.

[22] Many modern scholars have therefore expressed doubt that the author of Luke-Acts was the physician Luke, and critical opinion on the subject was assessed to be roughly evenly divided near the end of the 20th century.

[24] The interpretation of the "we" passages in Acts as indicative that the writer relied on a historical eyewitness (whether Luke the evangelist or not), remains the most influential in current biblical studies.

[25] Objections to this viewpoint, among others, include the claim that Luke-Acts contains differences in theology and historical narrative which are irreconcilable with the authentic letters of Paul the Apostle.

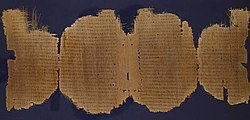

[9] Most scholars date the composition of the combined work to around 80–110 AD, and there is textual evidence (the conflicts between Western and Alexandrian manuscript families) that Luke–Acts was still being substantially revised well into the 2nd century.

"[36] Following the author's preface addressed to his patron and the two birth narratives (John the Baptist and Jesus), the gospel opens in Galilee and moves gradually to its climax in Jerusalem:[37] The structure of Acts parallels the structure of the gospel, demonstrating the universality of the divine plan and the shift of authority from Jerusalem to Rome:[38] Luke's theology is expressed primarily through his overarching plot, the way scenes, themes and characters combine to construct his specific worldview.

[39] His "salvation history" stretches from the Creation to the present time of his readers, in three ages: first, the time of "the Law and the Prophets", the period beginning with Genesis and ending with the appearance of John the Baptist;[40] second, the epoch of Jesus, in which the Kingdom of God was preached;[41] and finally the period of the Church, which began when the risen Christ was taken into Heaven, and would end with his second coming.

[49][50] Many of these differences may be due to scribal error, but others are argued to be deliberate alterations to doctrinally unacceptable passages, or the introduction by scribes of "proofs" for their favourite theological tenets.

[52] It is clear, however, that Luke understands the enabling power of the Spirit, expressed through non-discriminatory fellowship ("All who believed were together and had all things in common"), to be the basis of the Christian community.

[56] The gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke share so much in common that they are called the Synoptics, as they frequently cover the same events in similar and sometimes identical language.

The majority opinion among scholars is that Mark was the earliest of the three (about 70 AD) and that Matthew and Luke both used this work and the "sayings gospel" known as Q as their basic sources.

[65] While no manuscript copies of Marcion's gospel survive, reconstructions of his text have been published by Adolf von Harnack and Dieter T. Roth,[66] based on quotations in the anti-Marcionite treatises of orthodox Christian apologists, such as Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Epiphanius.