Apollonius of Perga

Beginning from the earlier contributions of Euclid and Archimedes on the topic, he brought them to the state prior to the invention of analytic geometry.

His hypothesis of eccentric orbits to explain the apparently aberrant motion of the planets, commonly believed until the Middle Ages, was superseded during the Renaissance.

[4] Ptolemy III Euergetes ("benefactor") was third Greek dynast of Egypt in the Diadochi succession, who reigned 246–222/221 BC.

During the last half of the 3rd century BC, Perga changed hands a number of times, being alternatively under the Seleucids and under the Attalids of Pergamon to the north.

[5] Basilides of Tyre, O Protarchus, when he came to Alexandria and met my father, spent the greater part of his sojourn with him on account of the bond between them due to their common interest in mathematics.

Research in Greek mathematical institutions, which followed the model of the Athenian Lycaeum, was part of the educational effort to which the library and museum were adjunct.

Apollonius reminds Eudemus that Conics was initially requested by Naucrates, a geometer and house guest at Alexandria otherwise unknown to history.

Whether the meeting indicates that Apollonius now lived in Ephesus is unresolved; the intellectual community of the Mediterranean was cosmopolitan and scholars in this "golden age of mathematics" sought employment internationally, visited each other, read each other's works and made suggestions, recommended students, and communicated via some sort of postal service.

In Preface VII Apollonius describes Book VIII as "an appendix ... which I will take care to send you as speedily as possible."

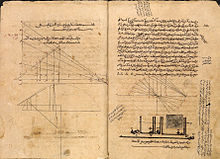

Books 5-7 are only preserved via an Arabic translation by Thābit ibn Qurra commissioned by the Banū Mūsā; the original Greek is lost.

The Greek geometers were interested in laying out select figures from their inventory in various applications of engineering and architecture, as the great inventors, such as Archimedes, were accustomed to doing.

The authors cite Euclid, Elements, Book III, which concerns itself with circles, and maximum and minimum distances from interior points to the circumference.

As with some of Apollonius other specialized topics, their utility today compared to Analytic Geometry remains to be seen, although he affirms in Preface VII that they are both useful and innovative; i.e., he takes the credit for them.

As few mathematical manuscripts were written in Latin, the editors of the early printed works translated from Greek or Arabic.

The difficulty of Conics made an intellectual niche for later commentators, each presenting Apollonius in the most lucid and relevant way for his own times.

His extensive prefatory commentary includes such items as a lexicon of Apollonian geometric terms giving the Greek, the meanings, and usage.

[17] Commenting that "the apparently portentious bulk of the treatise has deterred many from attempting to make its acquaintance",[18] he promises to add headings, changing the organization superficially, and to clarify the text with modern notation.

St. John's College (Annapolis/Santa Fe), which had been a military school since colonial times, preceding the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, to which it is adjacent, in 1936 lost its accreditation and was on the brink of bankruptcy.

In desperation the board summoned Stringfellow Barr and Scott Buchanan from the University of Chicago, where they had been developing a new theoretical program for instruction of the Classics.

Contemporaneously with Taliaferro's work, Ivor Thomas an Oxford don of the World War II era, was taking an intense interest in Greek mathematics.

De Sectione Determinata deals with problems in a manner that may be called an analytic geometry of one dimension; with the question of finding points on a line that were in a ratio to the others.

The history of the problem is explored in fascinating detail in the preface to J. W. Camerer's brief Apollonii Pergaei quae supersunt, ac maxime Lemmata Pappi in hos Libras, cum Observationibus, &c (Gothae, 1795, 8vo).

Heath says, As a preliminary to the consideration in detail of the methods employed in the Conics, it may be stated generally that they follow steadily the accepted principles of geometrical investigation which found their definitive expression in the Elements of Euclid.When referring to golden age geometers, modern scholars use the term "method" to mean the visual, reconstructive way in which the geometer produces a result equivalent to that produced by algebra today.

[k] The term had been defined by Henry Burchard Fine in 1890 or before, who applied it to La Géométrie of René Descartes, the first full-blown work of analytic geometry.

Variables are defined in Apollonius by such word statements as “let AB be the distance from any point on the section to the diameter,” a practice that continues in algebra today.

One well-known exception is the indispensable Pythagorean Theorem, even now represented by a right triangle with squares on its sides illustrating an expression such as a2 + b2 = c2.

The rectilinear distance from a point on the section to the diameter is termed tetagmenos in Greek, etymologically simply “extended.” As it is only ever extended “down” (kata-) or “up” (ana-), the translators interpret it as ordinate.

Carl Boyer, a modern historian of mathematics, therefore says:[25] However, Greek geometric algebra did not provide for negative magnitudes; moreover, the coordinate system was in every case superimposed a posteriori upon a given curve in order to study its properties .... Apollonius, the greatest geometer of antiquity, failed to develop analytic geometry....Nevertheless, according to Boyer, Apollonius' treatment of curves is in some ways similar to the modern treatment, and his work seems to anticipate analytical geometry.

Book V of Euclid begins by insisting that a magnitude (megethos, “size”) must be divisible evenly into units (meros, “part”).

There follows perhaps the most useful fundamental definition ever devised in science: the ratio (Greek logos, meaning roughly “explanation.”) is a statement of relative magnitude.