Arabic alphabet

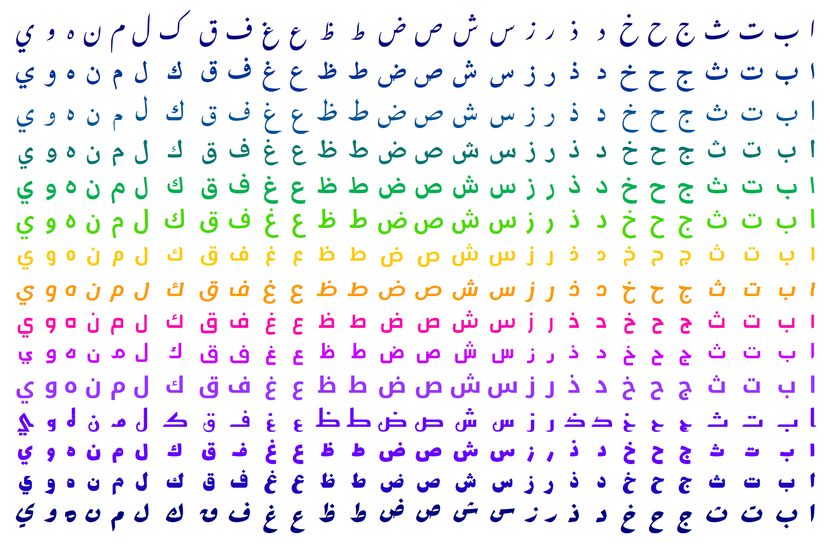

The original Abjadi order (أَبْجَدِيّ ʾabjadiyy /ʔabd͡ʒadijj/) derives from that used by the Phoenician alphabet and therefore resembles the sequence of letters in Hebrew and Greek.

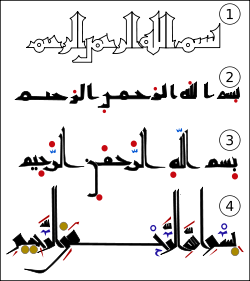

Letters can exhibit up to four distinct forms corresponding to an initial, medial (middle), final, or isolated position (IMFI).

(تَاءْ مَرْبُوطَة) used in final position, often for denoting singular feminine noun/word or to make the noun/word feminine, it has two pronunciations rules; often unpronounced or pronounced /h/ as in مدرسة madrasa [madrasa] / madrasah [madrasah] "school" and pronounced /t/ in construct state as in مدرسة سارة madrasatu sāra "Sara's school".

plural nouns: āt (a preceding letter followed by a fatḥah alif + tāʾ = ـَات) In the fully vocalized Arabic text found in texts such as the Quran, a long ā following a consonant other than a hamzah is written with a short a sign (fatḥah) on the consonant plus an ʾalif after it; long ī is written as a sign for short i (kasrah) plus a yāʾ; and long ū as a sign for short u (ḍammah) plus a wāw.

The table below shows vowels placed above or below a dotted circle replacing a primary consonant letter or a shaddah sign.

For clarity in the table, the primary letters on the left used to mark these long vowels are shown only in their isolated form.

In addition, when transliterating names and loanwords, Arabic language speakers write out most or all the vowels as long (ā with ا ʾalif, ē and ī with ي yaʾ, and ō and ū with و wāw), meaning it approaches a true alphabet.

The diphthongs حروف اللين ḥurūfu l-līn /aj/ and /aw/ are represented in vocalized text as follows: A final yaʾ is usually written at the end of words for nisba (اَلنِّسْبَة nisbah) which is a common suffix to form adjectives of relation or pertinence.

The suffix is ـِيّ -iyy for masculine (ـِيَّة -iyya(t)- for feminine); for example اِشْتِرَاكِيّ ištirākiyy "socialist", it is also used for a singulative ending that applies to human or other sentient beings as in جندي jundiyy "a soldier".

A similar mistake happens at the end of some third person plural verbs as in جَرَوْا jaraw "they ran" which is pronounced nowadays as جَرُوا jarū /d͡ʒaruː/.

In the Arabic handwriting of everyday use, in general publications, and on street signs, short vowels are typically not written.

On the other hand, copies of the Qur’ān cannot be endorsed by the religious institutes that review them unless the diacritics are included.

Children's books, elementary school texts, and Arabic-language grammars in general will include diacritics to some degree.

Short vowels may be written with diacritics placed above or below the consonant that precedes them in the syllable, called ḥarakāt.

In written Arabic nunation is indicated by doubling the vowel diacritic at the end of the word; e.g. شُكْرًا šukran [ʃukran] "thank you".

ــّـ An Arabic syllable can be open (ending with a vowel) or closed (ending with a consonant): A normal text is composed only of a series of consonants plus vowel-lengthening letters; thus, the word qalb, "heart", is written qlb, and the word qalaba "he turned around", is also written qlb.

The phoneme /ɡ/ (considered a standard pronunciation of ج in Egypt, Oman, and coastal Yemen) has the highest number of variations when writing loanwords or foreign proper nouns in Literary Arabic, and it can be written with either the standard letters ج, غ, ق, and ك or with the non-standard letters ڨ (used only in Tunisia and Algeria), ڭ (used only in Morocco), and گ (used mainly in Iraq) for example "Golf" pronounced /ɡoːlf/ can be written جولف, غولف, قولف, كولف, ڨولف, ڭولف or گولف depending on the writer and their country of origin.

أ ʾalif is 1, ب bāʾ is 2, ج jīm is 3, and so on until ي yāʾ = 10, ك kāf = 20, ل lām = 30, ..., ر rāʾ = 200, ..., غ ghayn = 1000.

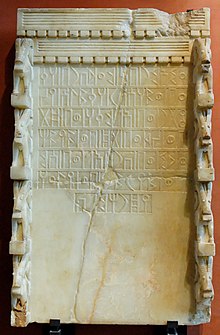

Later still, vowel marks and the hamza were introduced, beginning some time in the latter half of the 7th century, preceding the first invention of Syriac and Tiberian vocalizations.

In 1514, following Johannes Gutenberg's invention of the printing press in 1450, Gregorio de Gregorii, a Venetian, published an entire book of hours in Arabic script; it was entitled Kitab Salat al-Sawa'i and was intended for eastern Christian communities.

[21] Maronite monks at Monastery of Qozhaya on Mount Lebanon published the first Arabic books to use movable type in the Middle East.

A goldsmith (like Gutenberg) designed and implemented an Arabic script movable type printing press in the Middle East.

Each letter has a position-independent encoding in Unicode, and the rendering software can infer the correct glyph form (initial, medial, final or isolated) from its joining context.

However, for compatibility with previous standards, the initial, medial, final and isolated forms can also be encoded separately.

The Arabic Extended-A range encodes additional Qur'anic annotations and letter variants used for various non-Arabic languages.

The Arabic Presentation Forms-A range encodes contextual forms and ligatures of letter variants needed for Persian, Urdu, Sindhi and Central Asian languages.

Again, it is left to the rendering engine to present the characters in the correct direction, using Unicode's bi-directional text features.

In this regard, if the Arabic words on this page are written left to right, it is an indication that the Unicode rendering engine used to display them is out of date.

[26] The first software program of its kind in the world that identifies Arabic handwriting in real time was developed by researchers at Ben-Gurion University (BGU).

The error rate is less than three percent, according to Dr. Jihad El-Sana, from BGU's department of computer sciences, who developed the system along with master's degree student Fadi Biadsy.

1. alif

2. hamzat waṣl ( ْهَمْزَة وَصْل )

3. lām

4. lām

5. shadda ( شَدَّة )

6. dagger alif ( أَلِفْ خَنْجَریَّة )

7. hāʾ