Arrhenius equation

In physical chemistry, the Arrhenius equation is a formula for the temperature dependence of reaction rates.

The equation was proposed by Svante Arrhenius in 1889, based on the work of Dutch chemist Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff who had noted in 1884 that the Van 't Hoff equation for the temperature dependence of equilibrium constants suggests such a formula for the rates of both forward and reverse reactions.

This equation has a vast and important application in determining the rate of chemical reactions and for calculation of energy of activation.

[5]: 188 It can be used to model the temperature variation of diffusion coefficients, population of crystal vacancies, creep rates, and many other thermally induced processes and reactions.

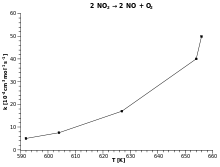

The Arrhenius equation describes the exponential dependence of the rate constant of a chemical reaction on the absolute temperature as

(3) can be treated as being equal to zero, so that and Integrating these equations and taking the exponential yields the results

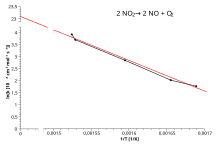

where x is the reciprocal of T. So, when a reaction has a rate constant obeying the Arrhenius equation, a plot of ln k versus T−1 gives a straight line, whose slope and intercept can be used to determine Ea and A respectively.

The activation energy is simply obtained by multiplying by (−R) the slope of the straight line drawn from a plot of ln k versus (1/T):

The modified Arrhenius equation[12] makes explicit the temperature dependence of the pre-exponential factor.

Theoretical analyses yield various predictions for n. It has been pointed out that "it is not feasible to establish, on the basis of temperature studies of the rate constant, whether the predicted T1/2 dependence of the pre-exponential factor is observed experimentally".

[5]: 190 However, if additional evidence is available, from theory and/or from experiment (such as density dependence), there is no obstacle to incisive tests of the Arrhenius law.

This is typically regarded as a purely empirical correction or fudge factor to make the model fit the data, but can have theoretical meaning, for example showing the presence of a range of activation energies or in special cases like the Mott variable range hopping.

At an absolute temperature T, the fraction of molecules that have a kinetic energy greater than Ea can be calculated from statistical mechanics.

The concept of activation energy explains the exponential nature of the relationship, and in one way or another, it is present in all kinetic theories.

The calculations for reaction rate constants involve an energy averaging over a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution with

as lower bound and so are often of the type of incomplete gamma functions, which turn out to be proportional to

One approach is the collision theory of chemical reactions, developed by Max Trautz and William Lewis in the years 1916–18.

In this theory, molecules are supposed to react if they collide with a relative kinetic energy along their line of centers that exceeds Ea.

The number of binary collisions between two unlike molecules per second per unit volume is found to be[13]

However for many reactions this agrees poorly with experiment, so the rate constant is written instead as

is an empirical steric factor, often much less than 1.00, which is interpreted as the fraction of sufficiently energetic collisions in which the two molecules have the correct mutual orientation to react.

[13] The Eyring equation, another Arrhenius-like expression, appears in the "transition state theory" of chemical reactions, formulated by Eugene Wigner, Henry Eyring, Michael Polanyi and M. G. Evans in the 1930s.

The overall expression again takes the form of an Arrhenius exponential (of enthalpy rather than energy) multiplied by a slowly varying function of T. The precise form of the temperature dependence depends upon the reaction, and can be calculated using formulas from statistical mechanics involving the partition functions of the reactants and of the activated complex.

Both the Arrhenius activation energy and the rate constant k are experimentally determined, and represent macroscopic reaction-specific parameters that are not simply related to threshold energies and the success of individual collisions at the molecular level.

[15] Another situation where the explanation of the Arrhenius equation parameters falls short is in heterogeneous catalysis, especially for reactions that show Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics.

Clearly, molecules on surfaces do not "collide" directly, and a simple molecular cross-section does not apply here.

[16] There are deviations from the Arrhenius law during the glass transition in all classes of glass-forming matter.

[17] The Arrhenius law predicts that the motion of the structural units (atoms, molecules, ions, etc.)

In other words, the structural units slow down at a faster rate than is predicted by the Arrhenius law.

The thermal energy must be high enough to allow for translational motion of the units which leads to viscous flow of the material.