Indo-European migrations

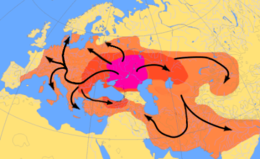

Colin Renfrew's Anatolian hypothesis suggests a much earlier date for the Indo-European languages, proposing an origin in Anatolia and an initial spread with the earliest farmers who migrated to Europe.

Over a century later, after learning Sanskrit in India, Sir William Jones detected systematic correspondences; he described them in his Third Anniversary Discourse to the Asiatic Society in 1786, concluding that all these languages originated from the same source.

[1] Using a mathematical analysis borrowed from evolutionary biology, but basing their work on comparative vocabulary, a number of researchers have attempted to estimate the dates of the splitting up of the various Indo-European languages.

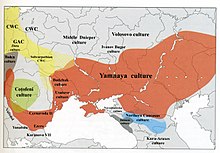

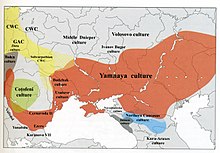

[52] It is understood as a migration of Yamnaya people to Europe, as military victors, successfully imposing a new administrative system, language and religion upon the indigenous groups, who are referred to by Gimbutas as Old Europeans.

According to some archaeologists, PIE speakers cannot be assumed to have been a single, identifiable people or tribe, but were a group of loosely related populations ancestral to the later, still partially prehistoric, Bronze Age Indo-Europeans.

[10][96][97][98][39][40][41][99][note 11] Anthony (2019, 2020) criticizes the Southern/Caucasian origin proposals of Reich and Kristiansen, and rejects the possibility that the Bronze Age Maykop people of the Caucasus were a southern source of language and genetics of Indo-European.

Additionally, there is possible later influence, involving little genetic impact, in the later Neolithic or Bronze Age from the language of the Maykop culture to the south, which is hypothesized to have belonged to the North Caucasian family.

[87] According to Anthony, hunting-fishing camps from the lower Volga, dated 6200–4500 BCE, could be the remains of people who contributed the CHG-component, similar to the Hotu cave, migrating from northwestern Iran or Azerbaijan via the western Caspian coast.

"[web 8] This model was confirmed by a genetic study published in 2018, which attributed the origin of Maykop individuals to a migration of Eneolithic farmers from western Georgia towards the north side of the Caucasus.

[150] These movements of both Tocharians and Iranians into East Central Asia were not a mere footnote in the history of China but... were part of a much wider picture involving the very foundations of the world's oldest surviving civilization.

[web 13] The turning point occurred around the 5th to 4th centuries BCE with a gradual Mongolization of Siberia, while Eastern Central Asia (East Turkistan) remained Caucasian and Indo-European-speaking until well into the 1st millennium CE.

At the peak of their power in the 3rd century BC, the Yuezhi are believed to have dominated the areas north of the Qilian Mountains (including the Tarim Basin and Dzungaria), the Altai region,[161] the greater part of Mongolia, and the upper waters of the Yellow River.

The Kushan empire stretched from Turfan in the Tarim Basin to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain at its greatest extent, and played an important role in the development of the Silk Road and the transmission of Buddhism to China.

"[170] The Yamnaya horizon represents the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society with stone idols, predominantly practising animal husbandry in permanent settlements protected by hillforts, subsisting on agriculture, and fishing along rivers.

[note 17] According to Sjögren et al. (2020), R1b-M269 "is the major lineage associated with the arrival of Steppe ancestry in western Europe after 2500 BC[E],"[187] and is strongly related to the Bell Beaker expansion.

[193] Between 3100 and 2800/2600 BCE, when the Yamnaya horizon spread fast across the Pontic Steppe, a real folk migration of Proto-Indo-European speakers from the Yamna-culture took place into the Danube Valley,[6] moving along Usatovo territory toward specific destinations, reaching as far as Hungary,[194] where as many as 3,000 kurgans may have been raised.

[195] According to Anthony (2007), Bell Beaker sites at Budapest, dated c. 2800–2600 BCE, may have aided in spreading Yamnaya dialects into Austria and southern Germany at their west, where Proto-Celtic may have developed.

[38] According to Lazaridis et al. (2022), the speakers of Albanian, Greek and other Paleo-Balkan languages, go back directly to the migration of Yamnaya steppe pastoralists into the Balkans about 5000 to 4500 years ago, admixting with the local populations.

[199] Recent research by Haak et al. found that four late Corded Ware people (2500–2300 BCE) buried at Esperstadt, Germany, were genetically very close to the Yamna-people, suggesting that a massive migration took place from the Eurasian steppes to Central Europe.

"[209] Heyd confirms the close connection between Corded Ware and Yamna, but also states that "neither a one-to-one translation from Yamnaya to CWC, nor even the 75:25 ratio as claimed (Haak et al. 2015:211) fits the archaeological record.

[241] By the later La Tène period (c. 450 BCE up to the Roman conquest), this Celtic culture had expanded by diffusion or migration to the British Isles (Insular Celts), France and The Low Countries (Gauls), Bohemia, Poland and much of Central Europe, the Iberian Peninsula (Celtiberians, Celtici and Gallaeci) and Italy (Golaseccans, Lepontii, Ligures and Cisalpine Gauls)[242] and, following the Gallic invasion of the Balkans in 279 BCE, as far east as central Anatolia (Galatians).

Most Indo-Europeanists classify Baltic and Slavic languages into a single branch, even though some details of the nature of their relationship remain in dispute[note 23] in some circles, usually due to political controversies.

[264] The Thracians inhabited a large area in southeastern Europe,[265] including parts of the ancient provinces of Thrace, Moesia, Macedonia, Dacia, Scythia Minor, Sarmatia, Bithynia, Mysia, Pannonia, and other regions of the Balkans and Anatolia.

[277] The Illyrians (Ancient Greek: Ἰλλυριοί, Illyrioi; Latin: Illyrii or Illyri) were a group of Indo-European tribes in antiquity, who inhabited part of the western Balkans and the southeastern coasts of the Italian peninsula (Messapia).

[282][283] The name "Illyrians", as applied by the ancient Greeks to their northern neighbors, may have referred to a broad, ill-defined group of peoples, and it is today unclear to what extent they were linguistically and culturally homogeneous.

[75] The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials, and the culture is considered a strong candidate for the origin of the technology, which spread throughout the Old World and played an important role in ancient warfare.

The associated culture was initially a tribal, pastoral society centred in the northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent; it spread after 1200 BCE to the Ganges Plain, as it was shaped by increasing settled agriculture, a hierarchy of four social classes, and the emergence of monarchical, state-level polities.

[339] Around the beginning of the Common Era, the Vedic tradition formed one of the main constituents of the so-called "Hindu synthesis"[340] According to Christopher I. Beckwith the Wusun, an Indo-European Caucasian people of Inner Asia in antiquity, were also of Indo-Aryan origin.

The Kushan empire stretched from Turfan in the Tarim Basin to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain at its greatest extent, and played an important role in the development of the Silk Road and the transmission of Buddhism to China.

Around the first millennium CE, the Kambojas, the Pashtuns and the Baloch began to settle on the eastern edge of the Iranian plateau, on the mountainous frontier of northwestern and western Pakistan, displacing the earlier Indo-Aryans from the area.

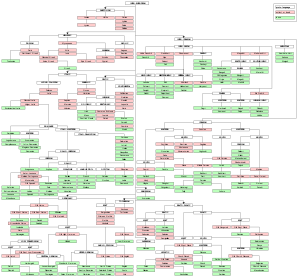

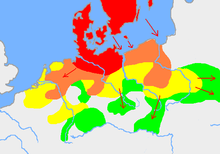

- Center: Steppe cultures

- 1 (black): Anatolian languages (archaic PIE)

- 2 (black): Afanasievo culture (early PIE)

- 3 (black): Yamnaya culture expansion (Pontic-Caspian steppe, Danube Valley; late PIE)

- 4A (black): Western Corded Ware

- 4B-C (blue & dark blue): Bell Beaker; adopted by Indo-European speakers

- 5A-B (red): Eastern Corded ware

- 5C (red): Sintashta (proto-Indo-Iranian)

- 6 (magenta): Andronovo

- 7A (purple): Indo-Aryans (Mittani)

- 7B (purple): Indo-Aryans (India)

- [NN] (dark yellow): proto-Balto-Slavic

- 8 (grey): Greek

- 9 (yellow): Iranians

Red: Extinct languages.

White: Categories or unattested proto-languages.

Left half: Centum languages.

Right half: Satem languages.

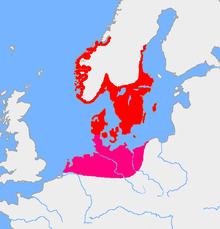

750 BC – AD 1 (after The Penguin Atlas of World History , 1988):