Astrolabe

In its simplest form it is a metal disc with a pattern of wires, cutouts, and perforations that allows a user to calculate astronomical positions precisely.

In addition to this, the lunar calendar that was informed by the calculations of the astrolabe was of great significance to the religion of Islam, given that it determines the dates of important religious observances such as Ramadan.

[8] An astrolabe is essentially a plane (two-dimensional) version of an armillary sphere, which had already been invented in the Hellenistic period and probably been used by Hipparchus to produce his star catalogue.

[18] Astrolabes were further developed in the medieval Islamic world, where Muslim astronomers introduced angular scales to the design,[19] adding circles indicating azimuths on the horizon.

[21] The mathematical background was established by Muslim astronomer Albatenius in his treatise Kitab az-Zij (c. 920 CE), which was translated into Latin by Plato Tiburtinus (De Motu Stellarum).

In the Islamic world, astrolabes were used to find the times of sunrise and the rising of fixed stars, to help schedule morning prayers (salat).

In the 10th century, al-Sufi first described over 1,000 different uses of an astrolabe, in areas as diverse as astronomy, astrology, navigation, surveying, timekeeping, prayer, Salat, Qibla, etc.

[27][28](p 140) Metal astrolabes avoided the warping that large wooden ones were prone to, allowing the construction of larger and therefore more accurate instruments.

[30](p 72) Peter of Maricourt wrote a treatise on the construction and use of a universal astrolabe in the last half of the 13th century entitled Nova compositio astrolabii particularis.

[32] English author Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343–1400) compiled A Treatise on the Astrolabe for his son, mainly based on a work by Messahalla or Ibn al-Saffar.

The astrolabe was almost certainly first brought north of the Pyrenees by Gerbert of Aurillac (future Pope Sylvester II), where it was integrated into the quadrivium at the school in Reims, France, sometime before the turn of the 11th century.

[28](p 143) In the 15th century, French instrument maker Jean Fusoris (c. 1365–1436) also started remaking and selling astrolabes in his shop in Paris, along with portable sundials and other popular scientific devices of the day.

Four identical 16th century astrolabes made by Georg Hartmann provide some of the earliest evidence for batch production by division of labor.

The painting, entitled Catherine of Alexandria; in addition to the saint, showed a device labelled the 'system of the universe' (Σύστημα τοῦ Παντός).

The device featured the classical planets with their Greek names: Helios (Sun), Selene (Moon), Hermes (Mercury), Aphrodite (Venus), Ares (Mars), Zeus (Jupiter), and Cronos (Saturn).

For example, Richard of Wallingford's clock (c. 1330) consisted essentially of a star map rotating behind a fixed rete, similar to that of an astrolabe.

For example, Swiss watchmaker Ludwig Oechslin designed and built an astrolabe wristwatch in conjunction with Ulysse Nardin in 1985.

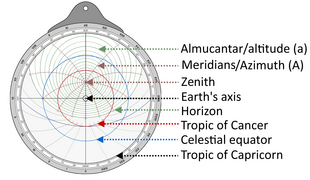

A tympan is made for a specific latitude and is engraved with a stereographic projection of circles denoting azimuth and altitude and representing the portion of the celestial sphere above the local horizon.

[42] Above the mater and tympan, the rete, a framework bearing a projection of the ecliptic plane and several pointers indicating the positions of the brightest stars, is free to rotate.

There are examples of astrolabes with artistic pointers in the shape of balls, stars, snakes, hands, dogs' heads, and leaves, among others.

[46] The date of the astrolabe's construction was often also signed, which has allowed historians to determine that these devices are the second oldest scientific instrument in the world.

The three concentric circles on the tympanum are useful for determining the exact moments of solstices and equinoxes throughout the year: if the sun's altitude at noon on the rete is known and coincides with the outer circle of the tympanum (Tropic of Capricorn), it signifies the winter solstice (the sun will be at the zenith for an observer at the Tropic of Capricorn, meaning summer in the southern hemisphere and winter in the northern hemisphere).

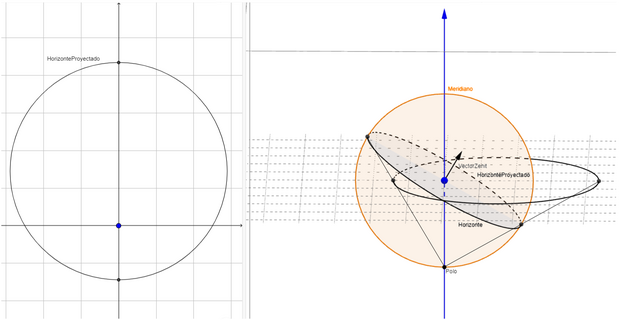

Additionally, when drawing circles parallel to the horizon up to the zenith (almucantar), and projecting them on the celestial equatorial plane, as in the image above, a grid of consecutive ellipses is constructed, allowing for the determination of a star's altitude when its rete overlaps with the designed tympanum.

On the right side of the image above: When projecting the celestial meridian, it results in a straight line that overlaps with the vertical axis of the tympanum, where the zenith and nadir are located.