Atmosphere of Titan

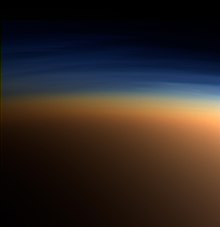

[7] The orange color as seen from space is produced by other more complex chemicals in small quantities, possibly tholins, tar-like organic precipitates.

[8] The presence of a significant atmosphere was first suspected by Spanish astronomer Josep Comas i Solà, who observed distinct limb darkening on Titan in 1903 from the Fabra Observatory in Barcelona, Catalonia.

[9] This observation was confirmed by Dutch astronomer Gerard P. Kuiper in 1944 using a spectroscopic technique that yielded an estimate of an atmospheric partial pressure of methane of the order of 100 millibars (10 kPa).

[10] Subsequent observations in the 1970s showed that Kuiper's figures had been significant underestimates; methane abundances in Titan's atmosphere were ten times higher, and the surface pressure was at least double what he had predicted.

[12] The joint NASA/ESA Cassini-Huygens mission provided a wealth of information about Titan, and the Saturn system in general, since entering orbit on July 1, 2004.

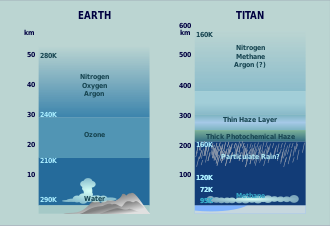

It supports opaque haze layers that block most visible light from the Sun and other sources and renders Titan's surface features obscure.

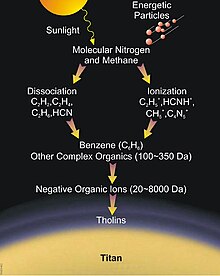

For instance, the hydrocarbons are thought to form in Titan's upper atmosphere in reactions resulting from the breakup of methane by the Sun's ultraviolet light, producing a thick orange smog.

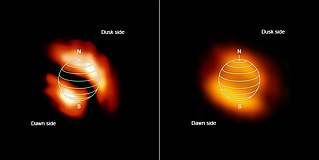

One interesting case was detected as an example of the coronal mass ejection impact onto Saturn's magnetosphere, causing Titan's orbit to be exposed to the shocked solar wind in the magnetosheath.

[38] The smaller negative ions have been identified as linear carbon chain anions with larger molecules displaying evidence of more complex structures, possibly derived from benzene.

[39] These negative ions appear to play a key role in the formation of more complex molecules, which are thought to be tholins, and may form the basis for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, cyanopolyynes and their derivatives.

[44] Energy from the Sun should have converted all traces of methane in Titan's atmosphere into more complex hydrocarbons within 50 million years — a short time compared to the age of the Solar System.

[51][50] On December 1, 2022, astronomers reported viewing clouds, likely made of methane, moving across Titan, using the James Webb Space Telescope.

[53][54] Sky brightness and viewing conditions are expected to be quite different from Earth and Mars due to Titan's farther distance from the Sun (~10 AU) and complex haze layers in its atmosphere.

[55] For astronauts who see with visible light, the daytime sky has a distinctly dark orange color and appears uniform in all directions due to significant Mie scattering from the many high-altitude haze layers.

[55] The daytime sky is calculated to be ~100–1000 times dimmer than an afternoon on Earth,[55] which is similar to the viewing conditions of a thick smog or dense fire smoke.

The sunsets on Titan are expected to be "underwhelming events",[55] where the Sun disappears about half-way up in the sky (~50° above the horizon) with no distinct change in color.

Similar to images of Martian sunsets from Mars rovers, a fan-like corona is seen to develop above the Sun due to scattering from haze or dust at high-altitudes.

This is due to two factors: the small optical depth of Titan's atmosphere at 5 microns[56][58] and the strong 5 μm emissions from Saturn's night side.

[59] In visible light, Saturn will make the sky on Titan's Saturn-facing side appear slightly brighter, similar to an overcast night with a full moon on Earth.

[57] From outer space, Cassini images from near-infrared to UV wavelengths have shown that the twilight periods (phase angles > 150°) are brighter than the daytime on Titan.

[60] The Titanean twilight outshining the dayside is due to a combination of Titan's atmosphere extending hundreds of kilometers above the surface and intense forward Mie scattering from the haze.

In fact, current interpretations suggest that only about 50% of Titan's mass is silicates,[66] with the rest consisting primarily of various H2O (water) ices and NH3·H2O (ammonia hydrates).

[68] Such an event could be driven by heating and photolysis effects of the early Sun's higher output of X-ray and ultraviolet (XUV) photons.

[71] Temperatures would have been even higher in the Jovian sub-nebula due to the greater gravitational potential energy release, mass, and proximity to the Sun, greatly reducing the NH3 inventory accreted by Callisto and Ganymede.

An alternative explanation is that cometary impacts release more energy on Callisto and Ganymede than they do at Titan due to the higher gravitational field of Jupiter.