Atrial flutter

Although this abnormal heart rhythm typically occurs in individuals with cardiovascular disease (e.g., high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, and cardiomyopathy) and diabetes mellitus, it may occur spontaneously in people with otherwise normal hearts.

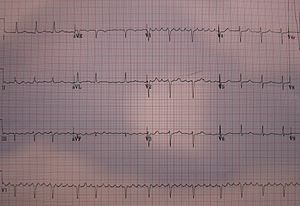

A supraventricular tachycardia with a ventricular heart rate of 150 beats per minute is suggestive (though not necessarily diagnostic) of atrial flutter.

Administration of adenosine in the vein (intravenously) can help medical personnel differentiate between atrial flutter and other forms of supraventricular tachycardia.

[2] Immediate treatment of atrial flutter centers on slowing the heart rate with medications such as beta blockers (e.g., metoprolol) or calcium channel blockers (e.g., diltiazem) if the affected person is not having chest pain, has not lost consciousness, and if their blood pressure is normal (known as stable atrial flutter).

This involves the insertion of a catheter through a vein in the groin which is followed up to the heart and is used to identify and interrupt the electrical circuit causing the atrial flutter (by creating a small burn and scar).

Atrial flutter was first identified as an independent medical condition in 1920 by the British physician Sir Thomas Lewis (1881–1945) and colleagues.

[3] While atrial flutter can sometimes go unnoticed, its onset is often marked by characteristic sensations of the heart feeling like it is beating too fast or hard.

[6] Atrial flutter is usually well-tolerated initially (a high heart rate is, for most people just a normal response to exercise); however, people with other underlying heart diseases (such as coronary artery disease) or poor exercise tolerance may rapidly develop symptoms, such as shortness of breath, chest pain, lightheadedness or dizziness, nausea and, in some patients, nervousness and feelings of impending doom.

This may manifest as exercise intolerance (exertional breathlessness), difficulty breathing at night, or swelling of the legs and/or abdomen.

Thus, any thrombus material that dislodges from this side of the heart can embolize (break off and travel) to the brain's arteries, with the potentially devastating consequence of a stroke.

Even if the ventricles are able to sustain a cardiac output at such a high rate, 1:1 flutter with time may degenerate into ventricular fibrillation, causing hemodynamic collapse and death.

This creates electrical activity that moves in a localized self-perpetuating loop, which usually lasts about 200 milliseconds for the complete circuit.

[citation needed] The impact and symptoms of atrial flutter depend on the heart rate of the affected person.

Individual flutter waves may be symmetrical, resembling p-waves, or maybe asymmetrical with a "sawtooth" shape, rising gradually and falling abruptly or vice versa.

Because both rhythms can lead to the formation of a blood clot in the atrium, individuals with atrial flutter usually require some form of anticoagulation or antiplatelet agent.

Both rhythms can be associated with dangerously fast heart rates and thus require medication to control the heart rate (such as beta blockers or calcium channel blockers) and/or rhythm control with class III antiarrhythmics (such as ibutilide or dofetilide).