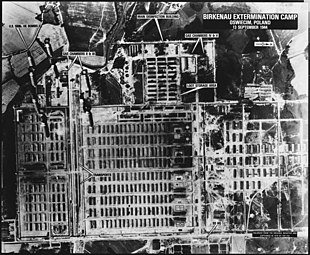

Auschwitz bombing debate

The issue of why the Allies did not act on early reports of atrocities in the Auschwitz concentration camp by destroying it or its railways by air during World War II has been a subject of controversy since the late 1970s.

In 1942, Lieutenant Jan Karski reported to the Polish, British and U.S. governments on the situation in occupied Poland, especially the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto and the general systematic extermination of the Poles and Jews nationally.

[3] The Polish Government—as the representatives of the legitimate authority on territories in which the Germans are carrying out the systematic extermination of Polish citizens and of citizens of Jewish origin of many other European countries—consider it their duty to address themselves to the Governments of the United Nations, in the confident belief that they will share their opinion as to the necessity not only of condemning the crimes committed by the Germans and punishing the criminals, but also of finding means offering the hope that Germany might be effectively restrained from continuing to apply her methods of mass extermination.Karski met also with many other government and civic leaders in the United States, including Felix Frankfurter, Cordell Hull, William Joseph Donovan, and Stephen Wise.

Karski presented his report to media, to bishops of various denominations (including Cardinal Samuel Stritch), to members of the Hollywood film industry and artists, but without success.

[5] In 1942, members of the Polish government in exile launched an official protest against systematic murders of Poles and Jews in occupied Poland, based on Karski's report.

In Poland, which has been made the principal Nazi slaughterhouse, the ghettoes established by the German invaders are being systematically emptied of all Jews except a few highly skilled workers required for war industries.

So far as the responsibility is concerned, I would certainly say it is the intention that all persons who can properly be held responsible for these crimes, whether they are the ringleaders or the actual perpetrators of the outrages, should be treated alike, and brought to book.On December 13, 1942, the Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom Joseph Hertz ordained a day of mourning to mark the suffering of "the numberless victims of the Satanic carnage".

[11] In 1942, Szmul Zygielbojm, a Jewish-Polish socialist politician, leader of the General Jewish Labor Bund in Poland, and member of the National Council of the Polish government in exile, wrote in English a booklet titled Stop Them Now.

[16][17] At the beginning of Operation Reinhard, the principal source of intelligence for the Western Allies about the existence of Auschwitz was the Witold's Report, forwarded via the Polish resistance to the British government in London.

It was written by the Polish Army Captain Witold Pilecki who spent a total of 945 days at the camp – the only known person to volunteer to be imprisoned at Auschwitz.

He forwarded his report about the camp to Polish resistance headquarters in Warsaw through the underground network known as Związek Organizacji Wojskowej which he organized inside Auschwitz.

[18] Pilecki hoped that either the Allies would drop weapons for the Armia Krajowa (AK) to organize an assault on the camp from the outside, or bring in the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade troops to liberate it.

918) organized a daring passing through the camp's gate along with three friends and co-conspirators, Stanisław Gustaw Jaster, Józef Lempart and Eugeniusz Bendera.

[21] The first written accounts of Auschwitz concentration camp were published in 1940/41 in the Polish underground newspapers Polska żyje ("Poland lives") and Biuletyn Informacyjny.

[22] From 1942 members of the Bureau of Information and Propaganda of the Warsaw Area Home Army also began to publish short booklets based on the experiences of escapees.

[27] Władysław Bartoszewski, himself a former Auschwitz inmate (camp number 4427), said in a speech: "The Polish resistance movement kept informing and alerting the free world to the situation.

In the introduction, editor Michael Neufeld wrote: "As David Wyman was able to show at the outset, it is impossible to claim that Auschwitz-Birkenau could not have been bombed.

On June 11, 1944, the Executive of the Jewish Agency considered the proposal, with David Ben-Gurion in the chair, and it specifically opposed the bombing of Auschwitz.

On June 28, Lesser met with A. Leon Kubowitzki, the head of the Rescue Department of the World Jewish Congress, who flatly opposed the idea.

On July 1, Kubowitzki followed up with a letter to War Refugee Board Director John W. Pehle, recalling his conversation with Lesser and stating: The destruction of the death installations can not be done by bombing from the air, as the first victims would be the Jews who are gathered in these camps, and such a bombing would be a welcome pretext for the Germans to assert that their Jewish victims have been massacred not by their killers, but by the Allied bombers.In June 1944, John Pehle of the War Refugee Board and Benjamin Akzin, a Zionist activist in America, urged the United States Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy to bomb the camps.

McCloy told his assistant to "kill" the request,[43] as the United States Army Air Forces had decided in February 1944 not to bomb anything "for the purposes of rescuing victims of enemy oppression", but to concentrate on military targets.

[41] On August 2, General Carl Andrew Spaatz, commander of the United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe, expressed sympathy for the idea of bombing Auschwitz.

Although Spaatz's officers had read Mann's message reporting acceleration of extermination activities in the camps in Poland, they could perceive no advantage to the victims in smashing the killing machinery, and decided not to bomb Auschwitz.

Historians Richard Breitman and Allan J. Lichtman argue that after Pearl Harbor: Roosevelt and his military and diplomatic advisers sought to unite the nation and blunt Nazi propaganda by avoiding the appearance of fighting a war for the Jews.

Every major American Jewish leader and organization that he respected remained silent on the matter, as did all influential members of Congress and opinion-makers in the mainstream media.

"[51] Kevin Mahoney, in an analysis of three requests submitted to the allies to bombard railway lines leading to Auschwitz, concludes that: The fate of the three requests to the MAAF in late August and early September 1944 dramatically illustrates why all proposals to bomb the rail facilities used to deport the Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz during 1944, as well as to bomb the camp itself, failed.