Historiography of the Battle of France

All this was so deeply disorienting because France had been regarded as a great power....The collapse of France, however, was a different case (a 'strange defeat' as it was dubbed in the haunting phrase of the Sorbonne's great medieval historian and Resistance martyr, Marc Bloch).While the French armies were being defeated, the government turned to elderly warriors from the First World War.

At a time many civilians felt there must be a wicked conspiracy afoot, these new leaders blamed a leftist culture inculcated by the schools for the failure, a theme that has repeatedly appeared in conservative commentary since 1940.

[2] The new national dictator of Vichy France, Marshal Philippe Pétain, had his explanation: "Our defeat is punishment for our moral failures.

In The French Defeat of 1940: Reassessments (1997), Stanley Hoffman, a Frenchman who taught political science at Harvard, wrote that there was no "1940 syndrome".

[14] Fuller had also written that the German army was an armoured battering-ram, covered by fighters and dive-bombers working as flying artillery, which broke through at several points.

[15] In 2000, American scholar Ernest R. May argued that Hitler had a better insight into the French and British governments than vice versa and knew that they would not go to war over Austria and Czechoslovakia, because he concentrated on politics rather than the state and national interest.

May referred to Wheeler-Bennett (1964), Except in cases where he had pledged his word, Hitler always meant what he said.and that in Paris, London and other capitals, there was an inability to believe that someone might want another world war.

[17] Hitler miscalculated Franco-British reactions to the invasion of Poland in September 1939, because he had not realised that a watershed in public opinion had occurred in mid-1939.

France did not invade Germany in 1939, because it wanted British lives to be at risk too and because of hopes that a blockade might force a German surrender without a bloodbath.

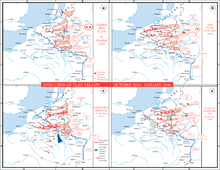

After the Mechelen Incident, OKH devised an alternative and hugely risky plan to make the invasion of Belgium a decoy, with the main effort switched to the Ardennes, to cross the Meuse and reach the Channel coast.

The results of the war games persuaded Halder that the Ardennes scheme could work, even though he and many other commanders still expected it to fail.

The French sought to assure the British that they would act to prevent the Luftwaffe using bases in the Netherlands and the Meuse valley and to encourage the Belgian and Dutch governments.

The insularity of the French and British intelligence agencies, meant that had they been asked if Germany would continue with a plan to attack across the Belgian plain after the Mechelen Incident, they would not have been able to point out how risky the Dyle-Breda variant was.

[21] May wrote that French and British rulers were at fault for tolerating poor performance by the intelligence agencies and that the Germans could achieve surprise in May 1940, showed that even with Hitler, the process of executive judgement in Germany had worked better than in France and Britain.

May referred to Marc Bloch in Strange Defeat (1940), that the German victory was a "triumph of intellect", which depended on Hitler's "methodical opportunism".

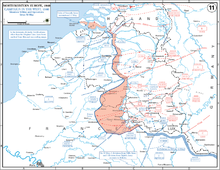

Prioux thought that a counter-offensive could still have worked up to 19 May but by then, Belgian refugees were crowded on the roads needed for redeployment and the French transport units, that had performed well in the advance into Belgium, failed for lack of plans to move them back.

By accident the German methods created a revolution in warfare, that France and its allies could not resist, still using the static thinking of the First World War.

OKH and OKW occasionally lost control and in such unique circumstances, some German commanders ignored orders and regulations, claiming the discretion to follow mission tactics, the most notable being the unauthorised break-out from the Sedan bridgehead by Guderian.

[25] In 2006, English historian Adam Tooze wrote that the German success could not be attributed to a great superiority in the machinery of industrial warfare.

There was no plan before September 1939 and the first version in October was a compromise that satisfied no-one but the capture the Channel coast to conduct an air war against Britain, was apparently the purpose determining armaments production from December 1939.

The incident was the catalyst for an alternative plan for an encircling move through the Ardennes proposed by Manstein but it came too late to change the armaments programme.

The blitzkrieg myth suited the Allies, because it did not refer to their military incompetence; it was expedient to exaggerate the excellence of German equipment.

The Germans avoided an analysis based on technical determinism, since this contradicted Nazi ideology and OKW attributed the victory to the "revolutionary dynamic of the Third Reich and its National Socialist leadership".

Tooze wrote that these expedients were limited to about 12 divisions and that the rest of the German army invaded France on foot, supplied by horse and cart from railheads as in 1914.

On 16 May, the day after the German breakthrough on the Meuse, Roosevelt laid before Congress a plan to create the greatest military-industrial complex in history, capable of building 50,000 aircraft a year.

Congress passed the Two-Ocean Navy Act and in September the US, for the first time, began conscription in peacetime to raise an army of 1.4 million men.

French centralised authority was not suited to the practice of hasty counter-attacks or bold manoeuvres, sometimes appearing to move in "slow motion".

Experience in Poland was used to improve the German army and make officers and units more flexible and a willingness to be pragmatic allowed reforms to be made which, while incomplete, showed their value in France.

Guderian had been free to move around during the fighting at Sedan, while Grandsard and Huntziger remained at their headquarters, unable to hurry on units and overrule hesitant commanders.

The French divisions suffered from poor organisation, doctrine, training, leadership and a lack of confidence in their weapons, which would have caused any unit to fail.