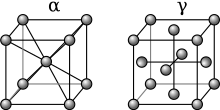

Austenite

This gamma form of iron is present in the most commonly used type of stainless steel[citation needed] for making hospital and food-service equipment.

A high cooling rate of thick sections will cause a steep thermal gradient in the material.

The outer layers of the heat treated part will cool faster and shrink more, causing it to be under tension and thermal straining.

At high cooling rates, the material will transform from austenite to martensite which is much harder and will generate cracks at much lower strains.

By alloying the steel with tungsten, the carbon diffusion is slowed and the transformation to BCT allotrope occurs at lower temperatures, thereby avoiding the cracking.

[10] Pearlite, a lamellar structure consisting of alternating layers of ferrite and cementite, forms through cooperative nucleation and growth processes from austenite.

[10] The decomposition of austenite is influenced by the cooling rate, which affects the morphology of carbides and thus the final steel structure.

[10] This difference in carbide morphology influences the rate and temperature at which austenite forms and decomposes during subsequent heat treatments.

[11][12] The addition of certain alloying elements, such as manganese and nickel, can stabilize the austenitic structure, facilitating heat-treatment of low-alloy steels.

In the extreme case of austenitic stainless steel, much higher alloy content makes this structure stable even at room temperature.

On the other hand, such elements as silicon, molybdenum, and chromium tend to de-stabilize austenite, raising the eutectoid temperature.

During heat treating, a blacksmith causes phase changes in the iron-carbon system to control the material's mechanical properties, often using the annealing, quenching, and tempering processes.