Ball and chain inactivation

The blockage is caused by a "ball" of amino acids connected to the main protein by a string of residues on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane.

[4] The suggestion of a physical basis for non-conductance came from experiments in squid giant axons, showing that internal treatment with pronase disrupted the inactivation phenomenon.

[6] Mutagenesis experiments have identified an intracellular string of amino acids as prime candidates for the pore blocker.

[5] The precise sequence of amino acids that makes up the channel-blocking ball in potassium channels was identified through the creation a synthetic peptide.

The peptide was built based on the sequence of a 20 amino acid residue from the Drosophila melanogaster's Shaker ShB protein and applied on the intracellular side of a non-inactivating channel in Xenopus oocytes.

[7] More recently, nuclear magnetic resonance studies in Xenopus oocyte BK channels have shed further light on the structural properties of the ball and chain domain.

[8] The introduction of the KCNMB2 β subunit to the cytoplasmic side of a non-inactivating channel restored inactivation, conforming to the expected behaviour of a ball and chain-type protein.

[10] Structural studies have shown that the inner pore of the potassium channel is accessible only through side slits between the cytoplasmic domains of the four α-subunits, rather than from a central route as previously thought.

[11] The ball domain enters the channel through the side slits and attaches to a binding site deep in the central cavity.

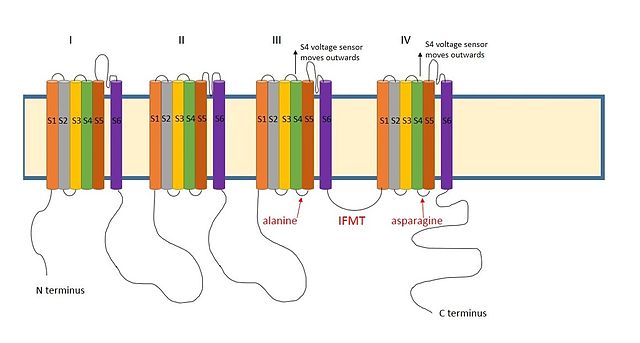

[12] A positively charged region between the III and IV domains of sodium channels is thought to act in a similar way.

[9] The essential region for inactivation in sodium channels is four amino acid sequence made up of isoleucine, phenylalanine, methionine and threonine (IFMT).

Lateral slits are also present in sodium channels,[16] suggesting that the access route for the ball domain may be similar.

[17] The mechanism of ball-and-chain inactivation is also distinct from that of voltage-dependent blockade by intracellular molecules or peptide regions of beta4 subunits in sodium channels.

[20] The effect is thought be stoichiometric, as the gradual introduction of un-tethered synthetic balls to the cytoplasm eventually restores inactivation.

[21] The interplay between opening and inactivation controls the firing pattern of a neuron by changing the rate and amount of ion flow through the channels.