Battery E, 1st Illinois Light Artillery Regiment

"[9] The next morning would prove Sherman fatally wrong, as he and the rest of the Union Army were attacked during breakfast by a large Confederate force under General Albert Sidney Johnston.

[17] The following is from Major Ezra Taylor's after-action report: The enemy appearing in large masses, and opening a battery to the front and right of the two guns, advanced across Owl Creek.

I instructed Captain Waterhouse to retire the two guns to the position occupied by the rest of his battery, about which time the enemy appeared in large force in the open field directly in front of the position of this battery, bearing aloft, as I supposed, the American flag, and their men and officers wearing uniforms so similar to ours, that I hesitated to open fire on them until they passed into the woods and were followed by other troops who wore a uniform not to be mistaken.

After instructing the battery to be cool and watch all the movements of the enemy, who was throwing large forces into the timber on the left of its position, I went to the position occupied by Taylor's battery and ordered Captain Barrett to open fire with shell, which was done promptly, causing the enemy to take shelter in the timber, under cover of which he advanced to within 150 yards of the guns, when they opened a tremendous fire of musketry, accompanied by terrific yells, showing their evident intent to intimidate our men; but the only effect it had on the men of this battery was to cause them promptly to move their guns by hand to the front and pouring into them a shower of canister, causing both the yelling and the firing of the enemy to cease for a time.

[18] Although inflicting severe losses on the attacking Southerners,[19] Appler's regiment ultimately broke and ran after its colonel lost his nerve, leaving Battery E unprotected and facing imminent annihilation by the Confederates.

[24] Viewing the imminent disintegration of his command, Sherman ordered the remnants of his division, including Battery E, to pull back and regroup on the Hamburg-Purdy Road, about 600 yards behind their current position.

[27][28] According to David Reed's history of the Battle, Battery E was engaged on its front by several different Southern regiments as the 13th Tennessee flanked it on the left side and attacked it from the rear, capturing its guns as the members beat a hasty retreat.

[29] Colonel (later General) Alfred Vaughan, commanding the 13th Tennessee, reported that when his regiment took possession of Battery E's guns they found "a dead Union officer [lying] near them, with a pointer dog that refused to allow the Confederates to approach the body.

The following morning the Federals counterattacked and the Southern army was forced to retreat to Corinth, giving the exhausted Northerners a victory in the bloodiest battle America had seen up to that time.

[37] On November 26, Battery E accompanied Sherman's expedition to Oxford, Mississippi, part of a larger operation undertaken by Grant against Confederate General John C. Pemberton's forces entrenched along the Tallahatchie River near Holly Springs.

It entered Holly Springs, Mississippi sometime prior to January 4, 1863, where Rice describes a scene of devastation left behind by Confederate General Earl van Dorn's raid on the town on December 20, 1862: "broken guns, dead horses, several unburned men, pieces of shells, lights out of every window, government wagons and ambulances half burnt up.

On February 19 and 20, the members of Battery E were witnesses to the burning of Hopefield, Arkansas, a small town across the river whose citizens had taken the Unionist Loyalty oath, but were secretly assisting local Confederate guerrillas.

"[52] Reaching Jackson on May 10, Battery E and the rest of their corps were appalled to discover that the Confederates had disemboweled numerous mules and hogs, then thrown their carcasses into every pond and well to contaminate the water.

[58] The "accurate fire" from Battery E and the Iowa artillery, coupled with the overwhelming Federal advantage in manpower, quickly forced the Confederates to retreat into their defensive works; within a matter of a few hours, Sherman's XV Corps had entered Jackson.

Some go and sharpshoot on their own hook; your Bote [here Rice is speaking of himself] has had a couple of bouts with them and tomorrow I'm going to have another... Get me an Enfield Rifle and shoot toward a Secesh... We have moved up to within 50 rods [825 feet] of the guns, and since I've been writing the boys have been giving them thunder.

[70] [citation needed] On 22 June Battery E relocated with two infantry brigades from the 3rd Division to Bear Creek on the exterior line, where it remained until Vicksburg was surrendered by General Pemberton on July 4, 1863.

[80] Having returned to Vicksburg, On July 23 Battery E went into camp on Bear Creek on Oak Ridge, where they were exceptionally troubled by chiggers and flies, not to mention the oppressive summer heat.

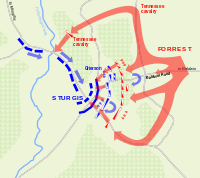

[87] Attacked by Confederates under General Forrest on both flanks at once, Colonel William McMillian, commanding the infantry on that portion of the field, ordered Battery E to sweep the Guntown Road with grapeshot and canister.

"[92] Fitch and the rest of Battery E managed to hold their ground until the last of the Federal regiments had passed, though by this time they were being fired on from front, left and rear—including the garden of a plantation house only seventy-five feet away.

Rice reports that when the butcher's bill was tallied, the battery had lost fifty horses, ten mules, three wagons, forty sets of harness, and four guns with their caissons.

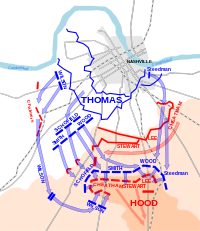

For my own part I cannot yet divine what will be the upshot of this raid, for we can turn peg-leg Hood's advent into this state ... My opinion is that Thomas will wait until he's good [and] ready, and then take the offensive instead of the defensive.

Rice relates his experience of the ensuing battle:[114] The morning of the fifteenth [of December] we had revile, and shortly afterwards the cavalry began to file out at the sally port by our battery until a whole division had massed in a solid square just outside of our picket line and were dismounted at parade rest.

followed them up all the afternoon and by night he had done his task, doubling their left back five miles onto its center ... To give you an idea of our lines, imagine a saucer broke into four exact pieces.

Rice continues his account:[115] The morning of the 16th dawned and at half past eight the cannons in front of the enemy began to roar and kept it up all day until 3 [PM], when a grand charge was made sweeping everything before.

"[116] One seven-by-eight foot wedge tent was provided for every three to four men in the battery; these were raised four feet off the ground on wooden platforms constructed by the troops, who then "embellished" them to suit the tastes of the occupants.

[117] The battery redeployed to Chattanooga on 21 February 1865, "after a 24-hour ride over the roughest RR in the U.S."[118] Rice reports that the train derailed at some point during its journey, but since it was only moving at ten miles-per-hour nobody was hurt.

Rice is saying this to his wife; he was on temporary duty as a hospital orderly at this time], I would have you come down and we would both go in; but a woman here is thought of no more than one of ill fame, and finely one can't honest stir out unless she is insulted.

[127] In another letter, Rice describes the antipathy many Federal soldiers felt following the issuance of Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863: To try to disguise or hide the facts that there is a great changing of ideas in the Army (and I think by what I read at home) would be useless.

Almost every hour in the day on the march, in the camp, off duty or on duty, in tent or by campfire, one can hear the following expressions: I be d-d if I enlisted to free niggers... if ole Abe doesn't retract his proclamation I hope the Northerners will get together and take the reins of government out of his hands, and thousands of other such expressions... For my part I am down on all such sentiments, I have pledged my arm to the government of my fathers, and thus it shall be raised come well, come woe.

[136] In a letter to his wife dated 7 May 1864, Private Rice recorded his own thoughts on the Federal cause, what a Confederate victory would mean for the nation, and the rampant corruption in governmental and economic circles: The war at present is almost at a standstill.