Battle of Palmito Ranch

The battle took place more than a month after the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia under Robert E. Lee to Union forces at Appomattox Court House, which had since been communicated to both commanders at Palmito.

Union forces were surprised by artillery said to have been supplied by the French Army garrison occupying the up-river Mexican town of Matamoros.

Casualty estimates are not dependable, but Union Private John J. Williams of the 34th Indiana Infantry Regiment is believed to have been the last man killed during the engagement.

After July 27, 1864, the Union Army withdrew most of the 6,500 troops deployed to the lower Rio Grande Valley, including Brownsville, which they had occupied since November 2, 1863.

The 34th Indiana deployed to Los Brazos de Santiago on December 22, 1864, replacing the 91st Illinois Volunteer Infantry, which returned to New Orleans.

He was replaced in the regiment by Lt. Col. Robert G. Morrison and at Los Brazos de Santiago by Colonel Theodore H. Barrett, commander of the 62nd U.S.C.T.

[5] Louis J. Schuler, in his 1960 pamphlet "The last battle in the War Between the States, May 13, 1865: Confederate Force of 300 defeats 1,700 Federals near Brownsville, Texas", asserts that Brig.

Volunteers had ordered the expedition to seize as contraband 2,000 bales of cotton stored in Brownsville and sell them for his own profit,[6] but Brown was not even appointed to command at Brazos Santiago until later in May.

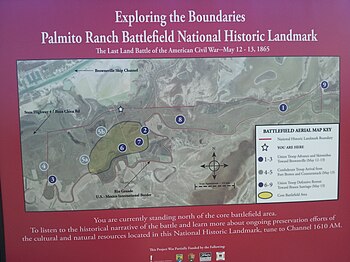

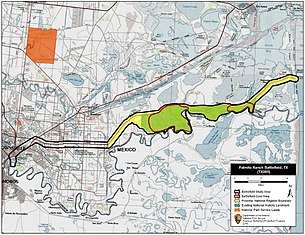

[7] According to historian Jerry Thompson: Union Lieutenant Colonel David Branson wanted to attack the Confederate encampments commanded by Ford at White and Palmito ranches near Fort Brown outside Brownsville.

[10] During the afternoon, Confederate forces under Captain William N. Robinson counterattacked with less than 100 cavalry, driving Branson back to White's Ranch, where the fighting stopped for the night.

Both sides sent for reinforcements; Ford arrived with six French guns and the remainder of his cavalry force (for a total of 300 men), while Barrett came with 200 troops of the 34th Indiana in nine under-strength companies.

[14] During the retreat, which lasted until 14 May, 50 members of the 34th Indiana's rearguard company, 30 stragglers, and 20 of the dismounted cavalry were surrounded in a bend of the Rio Grande and captured.

[18] Historian and Ford biographer Stephen B. Oates, however, concludes that Union deaths were much higher, probably around 30, many of whom drowned in the Rio Grande or were attacked by French border guards on the Mexican side.

[6][19] Using court-martial testimony and post returns from Brazos Santiago, historian Jerry D. Thompson of Texas A&M International University determined that: Private John J. Williams of the 34th Indiana was the last fatality during the Battle at Palmito Ranch, likely making him the final combat death of the entire war.

[23] Stand Watie, of the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles, on June 23, 1865, became the last Confederate general to surrender his forces, in Doaksville, Indian Territory.

[25] Many senior Confederate commanders in Texas (including Smith, Walker, Slaughter, and Ford) and many troops with their equipment fled across the border to Mexico.

Gen. Wesley Merritt and Maj. Gen. George A. Custer, it aggregated a 50,000-man force on the Gulf Coast and along the Rio Grande to pressure the French intervention in Mexico and garrison the Reconstruction Department of Texas.

Union records show that the last Northern soldier killed in combat during the war was Corporal John W. Skinner in this action.

[28][29] Historian Richard Gardiner stated in 2013 that on May 10, 1865: The Confederates won this engagement, but as there was no organized command structure, there has been controversy about the Union casualties.

The assistant secretary to the commissioner overturned the pension cut, legally ruling the men as the last Union casualties of the war.