Beverage-can stove

The design is popular in ultralight backpacking due to its low cost and lighter weight than commercial stoves.

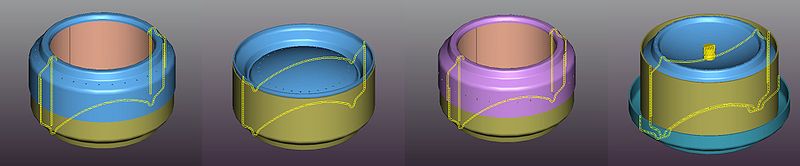

In the unpressurized open-top design the double wall acts as a gas generator, transferring heat from the flame to the fuel.

Once the fuel has warmed up, its vapor will travel up the hollow wall, pass through the perforations, and form a ring of flame.

A wick may be inserted into the hollow wall, where it will draw fuel upwards closer to the hot parts of the burner.

The wick will not burn because the evaporating fuel keeps it cool; also the pressure inside prevents oxygen from entering the hollow until the burner can no longer produce enough gas to support a flame.

Cellulose cigarette filters wick fuel efficiently upwards but melt and burn in all but the least powerful designs.

Parts can be glued with silicone sealant, high-temperature epoxy, or sealed with aluminum (thermal) foil tape, although this is not necessary.

The choice of aluminium has several advantages—light weight, low cost, and good thermal conductivity to aid vaporization of fuel.

Steel beverage cans of the classic twelve ounces (340 g) design are still in limited use and while they are heat resistant, their coating will burn off and they will rust if not cared for.

When used to cook larger meals (greater than 2 cups (0.5 litres)), it is less efficient than a more-powerful stove which delivers more heat to a pot.

[6] The stove can outperform some commercial models in cold or high-altitude environments, where propane and butane canisters might fail.

Roland Mueser, in Long-Distance Hiking, surveyed hikers on the Appalachian Trail and found that this stove was the only design with a zero-percent failure rate.

The weight advantage of the beverage-can stove is diminished by the greater fuel consumption (especially on longer hikes), but may still be offset by its reliability and simplicity.

A stove with a deep well is wind and blow-out resistant — blowing into it can send burning alcohol flying.