Bible translations in the Middle Ages

The whole written Christian Bible, including the deuterocanonical books, was available in Koine Greek by about 100 AD,[citation needed] as were numerous apocryphal Gospels.

[citation needed] At the end of this period (c700s), Church of the East monasteries (so-called Nestorians) had translated the New Testament and Psalms (at least, the portions needed for liturgical use) from Syriac to Sogdian,[2] the lingua franca in Central Asia of the Silk Road,[3] which was an Eastern Iranian language with Chinese loanwords, written in letters and logograms derived from Aramaic script.

The earliest surviving complete manuscript of the entire Latin Bible is the Codex Amiatinus, produced in eighth century England at the double monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow.

Jerome's Latin Vulgate did not take complete traction among the churches in the West until the time of Charlemagne, when he sought to standardize script, texts, and rites within Western Christendom.

During the Migration Period Christianity spread to various peoples who had not been part of the old Roman Empire, and whose languages had as yet no written form, or only a very simple one, like runes.

However, the Vulgate remained the authoritative text, used universally in the West for scholarship and the liturgy, matching its continued use for other purposes such as religious literature and most secular books and documents.

A number of pre-Reformation Old English Bible translations survive, as do many instances of glosses in the vernacular, especially in the Gospels and the Psalms.

[7] Over time, biblical translations and adaptations were produced both within and outside the church, some as personal copies for religious or lay nobility, others for liturgical or pedagogical purposes.

The acts of Saint Gall contain a reference to the use of a vernacular interpreter in Mass as early as the 7th century, and the 813 Council of Tours acknowledged the need for translation and encouraged such.

[10] In the late Middle Ages, the prône portion of Pre-Tridentine Latin Mass would include such translations by the priest as needed during the vernacular homily.

[12]: 408 [13] In a pinch, this translation could be used as the sermon itself: inability or slackness to preach in the vernacular was repeatedly regarded as a failure of a priest's or bishop's duty, but must have happened over the centuries: John Purvey quoted Robert Grosseteste: If any priest says he cannot preach (i.e. give composed or extemporized vernacular sermons), one remedy is: resign; [...] Another remedy, if he does not want that, is: record (i.e., recollect or write out)[14] he in the week the naked text of the Sunday's gospel, that he understands the gross story, and tell it to the people, that is if he understands Latin and does it every week of the year.

They were rare in peripheral areas and with languages in flux that did not have vocabularies suitable to translate biblical terms, things and phrases.

[29] Recent scholarship has tended to challenge earlier historical narratives of the impossibility for late Medieval lay people to access biblical material in their vernacular, even if they were literate.

In the early 1990s, historians such as Sabrina Cobellini, discussing a corpus of over a thousand extant medieval vernacular Scripture manuscripts, identified five such narratives as quite pervasive among scholars of particular Western European nationalities, which she suggests all downplay contrary evidence of grass-roots lay distribution and use:[30] There are a number of partial Old English Bible translations (from the Latin) surviving, including the Old English Hexateuch, Wessex Gospels and the Book of Psalms, partly in prose and partly in a different verse version.

Others, now missing, are referred to in other texts, notably a lost translation of the Gospel of John into Old English by the Venerable Bede, which he is said to have completed shortly before his death around the year 735.

Alfred the Great had a number of passages of the Bible circulated in the vernacular about 900, and in about 970 an inter-linear translation was added in red to the Lindisfarne Gospels.

According to the historian Victoria Thompson, "although the Church reserved Latin for the most sacred liturgical moments almost every other religious text was available in English by the eleventh century".

[32] After the Norman Conquest, the Ormulum, produced by the Augustinian friar Orm of Lincolnshire around 1150, includes partial translations of the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles from Latin into the dialect of East Midland.

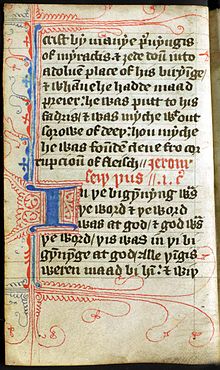

In the late 14th century, probably John Wycliffe and perhaps Nicholas Hereford produced the first complete Middle English language Bible.

Prior to the thirteenth century, the Narbonne school of glossators was an influential center of European Biblical translation, particularly for Jewish scholarship according to some scholars.

It translates from the Latin Vulgate significant portions from the Bible accompanied by selections from the Historia Scholastica by Peter Comestor (d. ca.

1178), a literal-historical commentary that summarizes and interprets episodes from the historical books of the Bible and situates them chronologically with respect to events from pagan history and mythology.

In the late Middle Ages, Deanesly thought that Bible translations were easier to produce in Germany, where the decentralized nature of the Empire allowed for greater religious freedom.

[41] Altogether there were 13 known medieval German translations before the Luther Bible,[42] including in the Saxon and Lower Rhenish dialects.

[47] Throughout the Middle Ages, Bible stories were always known in the vernacular through prose and poetic adaptations, usually greatly shortened and freely reworked, especially to include typological comparisons between Old and New Testaments.

15th century blockbook versions could be relatively cheap, and appear in the prosperous Netherlands to have included among their target market parish priests who would use them for instruction.

[48] Historians also used the Bible as a source and some of their works were later translated into a vernacular language: for example Peter Comestor's popular commentaries were incorporated into Guyart des Moulins' French translation, the Bible historiale and the Middle English Genesis and Exodus, and were an important source for a vast array of biblically-themed poems and histories in a variety of languages.