Biblical criticism

Against the backdrop of Enlightenment-era skepticism of biblical and church authority, scholars began to study the life of Jesus through a historical lens, breaking with the traditional theological focus on the nature and interpretation of his divinity.

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, biblical criticism was influenced by a wide range of additional academic disciplines and theoretical perspectives which led to its transformation.

Having long been dominated by white male Protestant academics, the twentieth century saw others such as non-white scholars, women, and those from the Jewish and Catholic traditions become prominent voices in biblical criticism.

Globalization introduced a broader spectrum of worldviews and perspectives into the field, and other academic disciplines, e.g. Near Eastern studies and philology, formed new methods of biblical criticism.

With these new methods came new goals, as biblical criticism moved from the historical to the literary, and its basic premise changed from neutral judgment to a recognition of the various biases the reader brings to the study of the texts.

[4]: 21, 22 In the Enlightenment era of the European West, philosophers and theologians such as Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), Benedict Spinoza (1632–1677), and Richard Simon (1638–1712) began to question the long-established Judeo-Christian tradition that Moses was the author of the first five books of the Bible known as the Pentateuch.

The existence of separate sources explained the inconsistent style and vocabulary of Genesis, discrepancies in the narrative, differing accounts and chronological difficulties, while still allowing for Mosaic authorship.

Herrick references the German theologian Henning Graf Reventlow (1929–2010) as linking deism with the humanist world view, which has been significant in biblical criticism.

[38]: 228 Supersessionism, instead of the more traditional millennialism, became a common theme in Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette (1780–1849), Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792–1860), David Strauss (1808–1874), Albrecht Ritschl (1822–1889), the history of religions school of the 1890s, and on into the form critics of the twentieth century until World War II.

[4]: 21, 22 New perspectives from different ethnicities, feminist theology, Catholicism and Judaism offered insights previously overlooked by the majority of white male Protestants who had dominated biblical criticism from its beginnings.

[4]: 22 In turn, this awareness changed biblical criticism's central concept from the criteria of neutral judgment to that of beginning from a recognition of the various biases the reader brings to the study of the texts.

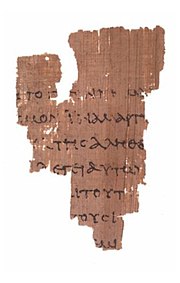

The divisions of the New Testament textual families were Alexandrian (also called the "Neutral text"), Western (Latin translations), and Eastern (used by churches centred on Antioch and Constantinople).

[81]: 212–215 Based on his study of Cicero, Clark argued omission was a more common scribal error than addition, saying "A text is like a traveler who goes from one inn to another losing an article of luggage at each halt".

[115]: 158 Form criticism began in the early twentieth century when theologian Karl Ludwig Schmidt observed that Mark's Gospel is composed of short units.

[121]: xiii Form criticism breaks down biblical pasage into short units called pericopes, which are then classified by genre: prose or verse, letters, laws, court archives, war hymns, poems of lament, and so on.

As John Niles indicates, the "older idea of 'an ideal folk community—an undifferentiated company of rustics, each of whom contributes equally to the process of oral tradition,' is no longer tenable".

[131]: 46 New Testament scholar N. T. Wright says, "The earliest traditions of Jesus reflected in the Gospels are written from the perspective of Second Temple Judaism [and] must be interpreted from the standpoint of Jewish eschatology and apocalypticism".

[note 8] Bible scholar Tony Campbell says: Form criticism had a meteoric rise in the early part of the twentieth century and fell from favor toward its end.

[136]: 100 Followers of other theories concerning the Synoptic problem, such as those who support the Greisbach hypothesis which says Matthew was written first, Luke second, and Mark third, have pointed to weaknesses in the redaction-based arguments for the existence of Q and Markan priority.

[141]: 3 [142] New Testament scholar Paul R. House says the discipline of linguistics, new views of historiography, and the decline of older methods of criticism were also influential in that process.

[152]: 166 Scholars such as Robert Alter and Frank Kermode sought to teach readers to "appreciate the Bible itself by training attention on its artfulness—how [the text] orchestrates sound, repetition, dialogue, allusion, and ambiguity to generate meaning and effect".

[155]: 126, 129 By the end of the twentieth century, multiple new points of view changed biblical criticism's central concepts and its goals, leading to the development of a group of new and different biblical-critical disciplines.

William Robertson Smith (1846–1894) is an example of a nineteenth century evangelical who believed historical criticism was a legitimate outgrowth of the Protestant Reformation's focus on the biblical text.

[166]: 140–142 Mark Noll says that "in recent years, a steadily growing number of well qualified and widely published scholars have broadened and deepened the impact of evangelical scholarship".

[166]: 135 Edwin M. Yamauchi is a recognized expert on Gnosticism; Gordon Fee has done exemplary work in textual criticism; Richard Longenecker is a student of Jewish-Christianity and the theology of Paul.

[166]: 136, 137, 141 Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Catholic theology avoided biblical criticism because of its reliance on rationalism, preferring instead to engage in traditional exegesis, based on the works of the Church Fathers.

Following Pius's death, Pope Benedict XV once again condemned rationalistic biblical criticism in his papal encyclical Spiritus Paraclitus ("Paraclete Spirit,[174][36]: 99, 100 but also took a more moderate line than his predecessor, allowing Lagrange to return to Jerusalem and reopen his school and journal.

[22]: 298 [175] The dogmatic constitution Dei verbum ("Word of God"), approved by the Second Vatican Council and promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1965 furtherly sanctioned biblical criticism.

[189]: 24–25 Carol L. Meyers says feminist archaeology has shown "male dominance was real; but it was fragmentary, not hegemonic" leading to a change in the anthropological description of ancient Israel as heterarchy rather than patriarchy.

Vaughn A. Booker writes that, "Such developments included the introduction of the varieties of American metaphysical theology in sermons and songs, liturgical modifications [to accommodate] Holy Spirit possession presences through shouting and dancing, and musical changes".

- Diagram showing the authors and editors of the Pentateuch (Torah) according to the Documentary hypothesis

- J: Yahwist (10th–9th century BCE)

- E: Elohist (9th century BCE)

- Dtr1: early (7th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- Dtr2: later (6th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- P*: Priestly (6th–5th century BCE)

- D†: Deuteronomist

- R: redactor

- DH: Deuteronomistic history (books of Joshua , Judges , Samuel , Kings )

- [ 97 ] : 62 [ 94 ] : 5