Biblical manuscript

Textual criticism attempts to reconstruct the original text of books, especially those published prior to the invention of the printing press.

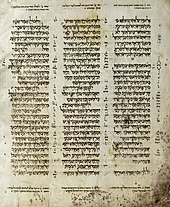

In 1947, the finding of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran pushed the manuscript history of the Tanakh back a millennium from such codices.

The dates of these manuscripts range from c. 125 (the 𝔓52 papyrus, oldest copy of John fragment) to the introduction of printing in Germany in the 15th century.

Since the manuscripts contained the words of Christ, they were thought to have had a level of sanctity;[citation needed] burning them was considered more reverent than simply throwing them into a garbage pit, which occasionally happened (as in the case of Oxyrhynchus 840).

When scholars come across manuscript caches, such as at Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai (the source of the Codex Sinaiticus), or Saint Sabbas Monastery outside Bethlehem, they are finding not libraries but storehouses of rejected texts[citation needed] sometimes kept in boxes or back shelves in libraries due to space constraints.

In addition, texts thought to be complete and correct but that had deteriorated from heavy usage or had missing folios would also be placed in the caches.

[citation needed] Complete and correctly copied texts would usually be immediately placed in use and so wore out fairly quickly, which required frequent recopying.

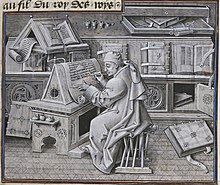

The size of the parchment, script used, any illustrations (thus raising the effective cost) and whether it was one book or a collection of several would be determined by the one commissioning the work.

Stocking extra copies would likely have been considered wasteful and unnecessary since the form and the presentation of a manuscript were typically customized to the aesthetic tastes of the buyer.

In the 6th century, a special room devoted to the practice of manuscript writing and illumination called the scriptorium came into use, typically inside medieval European monasteries.

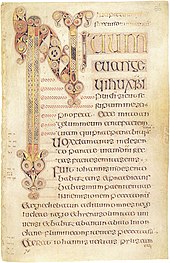

The earliest New Testament manuscripts were written on papyrus, made from a reed that grew abundantly in the Nile Delta.

[8] Beginning in the fourth century, parchment (also called vellum) began to be a common medium for New Testament manuscripts.

[9] It wasn't until the twelfth century that paper (made from cotton or plant fibers) began to gain popularity in biblical manuscripts.

[12] Scholars have argued that the codex was adopted as a product of the formation of the New Testament canon, allowing for specific collections of documents like the Gospels and the Pauline Epistles.

More formal, literary Greek works were often written in a distinctive style of even, capital letters called book-hand.

Scholars using careful examination can sometimes determine what was originally written on the material of a document before it was erased to make way for a new text (for example Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus and the Syriac Sinaiticus).

Constantin von Tischendorf found one of the earliest, nearly complete copies of the Bible, Codex Sinaiticus, over a century after Wettstein's cataloging system was introduced.

Because he felt the manuscript was so important, Von Tischendorf assigned it the Hebrew letter aleph (א).

[17] He grouped the manuscripts based on content, assigning them a Greek prefix: δ for the complete New Testament, ε for the Gospels, and α for the remaining parts.

The uncials were given a prefix of the number 0, and the established letters for the major manuscripts were retained for redundancy (e.g. Codex Claromontanus is assigned both 06 and D).

In the critical apparatus of the Novum Testamentum Graece, a series of abbreviations and prefixes designate different language versions (it for Old Latin, lowercase letters for individual Old Latin manuscripts, vg for Vulgate, lat for Latin, sys for Sinaitic Palimpsest, syc for Curetonian Gospels, syp for the Peshitta, co for Coptic, ac for Akhmimic, bo for Bohairic, sa for Sahidic, arm for Armenian, geo for Georgian, got for Gothic, aeth for Ethiopic, and slav for Old Church Slavonic).

Script groups belong typologically to their generation; and changes can be noted with great accuracy over relatively short periods of time.

[24] The earliest manuscript of a New Testament text is a business-card-sized fragment from the Gospel of John, Rylands Library Papyrus P52, which may be as early as the first half of the 2nd century.

The textual critic seeks to ascertain from the divergent copies which form of the text should be regarded as most conforming to the original.

Since the mid-19th century, eclecticism, in which there is no a priori bias to a single manuscript, has been the dominant method of editing the Greek text of the New Testament.

In textual criticism, eclecticism is the practice of examining a wide number of text witnesses and selecting the variant that seems best.

Instead of the lapse of a millennium or more, as is the case of not a few classical authors, several papyrus manuscripts of portions of the New Testament are extant which were copies within a century or so after the composition of the original documents.

[31][b] Biblical scholar Gary Habermas adds, What is usually meant is that the New Testament has far more manuscript evidence from a far earlier period than other classical works.

Some variations involve apparently intentional changes, which often make more difficult a determination of whether they were corrections from better exemplars, harmonizations between readings, or ideologically motivated.

[36] Variants are listed in critical editions of the text, the most important of which is the Novum Testamentum Graece, which is the basis for most modern translations.