William Blake

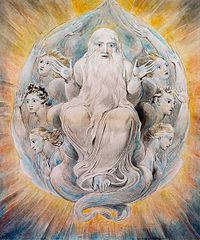

[2] While he lived in London his entire life, except for three years spent in Felpham,[3] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich collection of works, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God",[4] or "human existence itself".

[5] Although Blake was considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, he came to be highly regarded by later critics and readers for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work.

[6] A theist who preferred his own Marcionite style of theology,[7][8] he was hostile to the Church of England (indeed, to almost all forms of organised religion), and was influenced by the ideals and ambitions of the French and American Revolutions.

Blake's childhood, according to him, included mystical religious experiences such as "beholding God's face pressed against his window, seeing angels among the haystacks, and being visited by the Old Testament prophet Ezekiel.

Reynolds wrote in his Discourses that the "disposition to abstractions, to generalising and classification, is the great glory of the human mind"; Blake responded, in marginalia to his personal copy, that "To Generalize is to be an Idiot; To Particularize is the Alone Distinction of Merit".

[40] Johnson's house was a meeting-place for some leading English intellectual dissidents of the time: theologian and scientist Joseph Priestley; philosopher Richard Price; artist John Henry Fuseli;[41] early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft; and English-American revolutionary Thomas Paine.

In Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793), Blake condemned the cruel absurdity of enforced chastity and marriage without love and defended the right of women to complete self-fulfilment.

[50] Some scholars have speculated that the bracelets represent the "historical fact" of slavery in Africa and the Americas while the handclasp refer to Stedman's "ardent wish": "we only differ in color, but are certainly all created by the same Hand.

[54] Some biographers have suggested that Blake tried to bring a concubine into the marriage bed in accordance with the beliefs of the more radical branches of the Swedenborgian Society,[55] but other scholars have dismissed these theories as conjecture.

[63] Also around this time (circa 1808), Blake gave vigorous expression of his views on art in an extensive series of polemical annotations to the Discourses of Sir Joshua Reynolds, denouncing the Royal Academy as a fraud and proclaiming, "To Generalize is to be an Idiot".

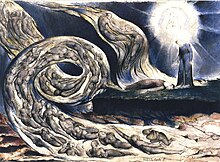

Even as he seemed to be near death, Blake's central preoccupation was his feverish work on the illustrations to Dante's Inferno; he is said to have spent one of the last shillings he possessed on a pencil to continue sketching.

Blake's body was buried in a plot shared with others, five days after his death – on the eve of his 45th wedding anniversary – at the Dissenter's burial ground in Bunhill Fields, that became the London Borough of Islington.

[75] The exact number of destroyed manuscripts is unknown, but shortly before his death Blake told a friend he had written "twenty tragedies as long as Macbeth", none of which survive.

[79][80] A Portuguese couple, Carol and Luís Garrido, rediscovered the exact burial location after 14 years of investigatory work, and the Blake Society organised a permanent memorial slab, which was unveiled at a public ceremony at the site on 12 August 2018.

His poetry consistently embodies an attitude of rebellion against the abuse of class power as documented in David Erdman's major study Blake: Prophet Against Empire: A Poet's Interpretation of the History of His Own Times (1954).

Erdman also notes Blake was deeply opposed to slavery and believes some of his poems, read primarily as championing "free love", had their anti-slavery implications short-changed.

[86] British Marxist historian E. P. Thompson's last finished work, Witness Against the Beast: William Blake and the Moral Law (1993), claims to show how far he was inspired by dissident religious ideas rooted in the thinking of the most radical opponents of the monarchy during the English Civil War.

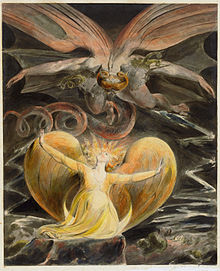

The earlier work is primarily rebellious in character and can be seen as a protest against dogmatic religion especially notable in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in which the figure represented by the "Devil" is virtually a hero rebelling against an imposter authoritarian deity.

In later works, such as Milton and Jerusalem, Blake carves a distinctive vision of a humanity redeemed by self-sacrifice and forgiveness, while retaining his earlier negative attitude towards what he felt was the rigid and morbid authoritarianism of traditional religion.

[88] Regarding conventional religion, Blake was a satirist and ironist in his viewpoints which are illustrated and summarised in his poem Vala, or The Four Zoas, one of his uncompleted prophetic books begun in 1797.

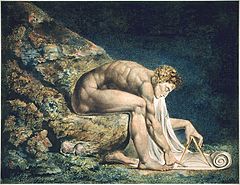

This mindset is reflected in an excerpt from Blake's Jerusalem: I turn my eyes to the Schools & Universities of Europe And there behold the Loom of Locke whose Woof rages dire Washd by the Water-wheels of Newton.

(E784)It has been supposed that, despite his opposition to Enlightenment principles, Blake arrived at a linear aesthetic that was in many ways more similar to the Neoclassical engravings of John Flaxman than to the works of the Romantics, with whom he is often classified.

[110] His poetry suggests that external demands for marital fidelity reduce love to mere duty rather than authentic affection, and decries jealousy and egotism as a motive for marriage laws.

Pierre Berger also analyses Blake's early mythological poems such as Ahania as declaring marriage laws to be a consequence of the fallenness of humanity, as these are born from pride and jealousy.

[123] Ankarsjö records Blake as having supported a commune with some sharing of partners, though David Worrall read The Book of Thel as a rejection of the proposal to take concubines espoused by some members of the Swedenborgian church.

"[129] According to Blake's Victorian biographer Gilchrist, he returned home and reported the vision and only escaped being thrashed by his father for telling a lie through the intervention of his mother.

I hear his advice, and even now write from his dictate.In a letter to John Flaxman, dated 21 September 1800, Blake wrote: [The town of] Felpham is a sweet place for Study, because it is more spiritual than London.

"[133] In a more deferential vein, John William Cousins wrote in A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature that Blake was "a truly pious and loving soul, neglected and misunderstood by the world, but appreciated by an elect few", who "led a cheerful and contented life of poverty illumined by visions and celestial inspirations".

Important early and mid-20th-century scholars involved in enhancing Blake's standing in literary and artistic circles included S. Foster Damon, Geoffrey Keynes, Northrop Frye and David V. Erdman.

While Blake had a significant role in the art and poetry of figures such as Rossetti, it was during the Modernist period that this work began to influence a wider set of writers and artists.