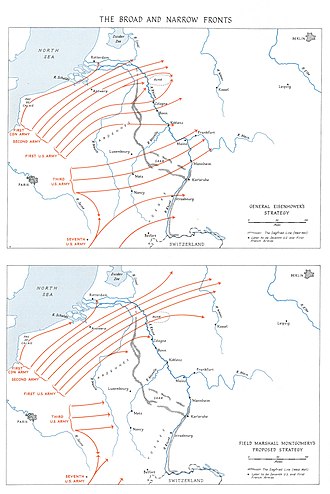

Broad front versus narrow front controversy in World War II

During the subsequent Cold War, suggestions were made that the Soviet presence in Eastern Europe might have been reduced had Eisenhower sent a narrow-front thrust to race the USSR to Berlin in 1945.

The staff at Eisenhower's Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) considered Montgomery's proposed advance on the Ruhr and Berlin and Bradley's proposed advance on Metz and the Saar, and assessed both to be feasible, but only on the assumptions that the port of Antwerp was brought rapidly into service, that considerable additional air, rail and road transportation became available, and that the other Allied armies were already poised on the German border.

The British historian A. J. P. Taylor credited Chester Wilmot's The Struggle For Europe (1952) as the work that "launched the myths that Eisenhower prevented Montgomery from winning the war in 1944".

"Wilmot's book", American historian Maurice Matloff wrote, "must be taken for what it represents—a suggestive, provocative work on the war written from a British point of view in a period of disenchantment.

In the weeks that followed, the Germans made skillful use of the difficult and defensible terrain of the bocage country, and the initial Allied advance was slower and more costly than anticipated.

Furthermore, the original plans had assumed a steady rate of advance against resistance, rather than the rapid pursuit of a disorganized enemy, and this assumption formed the basis of logistic preparations.

[27] Like his American counterparts, Montgomery's primary mission was to defeat Germany as quickly as possible, but as the senior British commander in north west Europe, he also operated under political pressure to achieve two other objectives.

[32] The fewer the number of combat-experienced divisions the British Army had left at the end of the war, the smaller Britain's influence in the reconstruction of Europe was likely to be, compared to the emerging superpowers of the US and the USSR.

Montgomery was thus caught in a dilemma—the British Army needed to be seen to be pulling at least half the weight in the liberation of Western Europe, but without incurring the heavy casualties that such a role would inevitably produce.

[33] Montgomery's solution to the dilemma was to lobby to be reappointed as commander of Allied land forces until the end of the war, so that any victory attained on the Western front—although achieved primarily by American formations—would accrue in part to him and thus to Britain.

[34] When that strategy failed, he lobbied Eisenhower to put some American formations under the control of the 21st Army Group, so as to bolster his resources while still maintaining the outward appearance of successful British effort.

[36] Initially it was logical to pursue the opportunities offered by the disintegration of enemy resistance, but the available transport was unable to deliver even daily needs, far less to stock advance supply depots.

It was thus accepted that the Saar and Ruhr areas were at the absolute maximum distance at which Allied forces could be supported for the time being, and that "a power thrust deep into Germany" could not be attempted without additional logistic capacity.

[55] By September, with the weather starting to deteriorate,[56] the Communications Zone was warning that it could not provide enough resources to maintain more than one army, and then only at the expense of deferring the construction of advance airfields, the winterisation of clothing and equipment, and the replacement of damaged and worn-out materiel.

However such deferments were no longer permissible, in view of the impending bad weather with its anticipated impact on the landing of supplies over the beaches, as well as the hardening of German resistance in prepared defensive positions.

[61] The following day Montgomery cabled the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke:Have been thinking about future plans but have not (repeat not) discussed the subject with Ike [Eisenhower].

Such an advance would have created exposed flanks and lines of communication of approximately 300 miles through enemy territory, air cover would have been difficult to maintain, and support from other Allied divisions would not have been available due to their own logistical shortages.

On 10 September Eisenhower authorised two US Armies to advance to both the Ruhr and the Saar, in the belief that the gamble was worth taking in order to fully exploit the disorganised state of the German forces.

The idea of aiming a powerful thrust deep into Germany was definitely abandoned, because any sustained drives would first require a major re-orientation toward shorter lines of communication based on the northern ports.

[82][83] Operation Market Garden was fought from 17 to 25 September 1944, and ended with a British defeat at the Battle of Arnhem when the ground forces were held up by German defenders on the narrow road, and could not reach the airborne troops in time.

[94] "Of all decisions made at the level of the Supreme Allied Commander in western Europe during World War II," American official historian Roland Ruppenthal wrote, "perhaps none has excited more polemics than that which raised the 'one-thrust-broad front' controversy.

[96] In his English History 1914–1945 (1965), the British historian A. J. P. Taylor credited Chester Wilmot's The Struggle For Europe (1952) as the work that "launched the myths that Eisenhower prevented Montgomery from winning the war in 1944".

[98] In response, Smith wrote a series of articles in The Saturday Evening Post in June and July that later formed the basis of his Eisenhower's Six Great Decisions (1956).

[110] In his memoir, Operation Victory, which was published in January 1947 and serialised in The Times, de Guingand provided an account of the wartime debate, in which he stated that he had opposed Montgomery's narrow front strategy on political and administrative grounds.

[111] Montgomery could not recall de Guingand ever dissenting with him about his strategy, and Graham wrote a letter to The Times, which was published on 24 February, defending his wartime contention that the narrow front advance was logistically feasible.

[112] In 1977, historian Martin van Creveld calculated that an advance as far as Dortmund was practical,[113] although he had reservations about whether the Allied logistical system possessed the required flexibility to provide a truly viable alternative to Eisenhower's broad front strategy.

[115] The vision of a rapid advance by Patton had the appeal of simplifying and personalising a complex military situation, but the reality of terrain and logistics argued strongly against it, and the capture of the Saar would not have prompted a German collapse.

[108] Carlo D'Este noted that "it is hard to ignore the suggestion that Eisenhower's broad front strategy had as much to do with politics as it did with logistical considerations and military philosophy.

He could not halt Patton in his tracks, relegate Bradley to a minor administrative role, and in effect tell Marshall that the great army he had raised in the United States was not needed in Europe.

Eisenhower was acutely aware that, especially in a presidential election year, the prejudices, preconceptions and attitudes of the American public and political class, not to mention the Army itself, were critical to his continuing command.